In the summer of 1817, when a young immigrant laborer stepped off a ship in Baltimore harbor, America's Catholic population was miniscule. Forty-seven years later, when that same immigrant died as New York's first Archbishop, Catholicism was the country's largest denomination. During the years in between, immigration reached unprecedented levels, anti-Catholicism vehemently reasserted itself, the Irish assumed leadership roles in their Church, and John Hughes ruled New York Catholics, writes one historian, "like an Irish chieftain." But as a peer said, he did it "with feeling."

In the summer of 1817, when a young immigrant laborer stepped off a ship in Baltimore harbor, America's Catholic population was miniscule. Forty-seven years later, when that same immigrant died as New York's first Archbishop, Catholicism was the country's largest denomination. During the years in between, immigration reached unprecedented levels, anti-Catholicism vehemently reasserted itself, the Irish assumed leadership roles in their Church, and John Hughes ruled New York Catholics, writes one historian, "like an Irish chieftain." But as a peer said, he did it "with feeling."

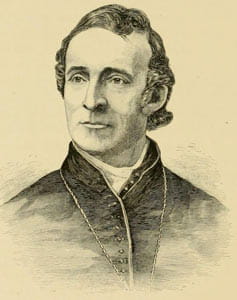

A fellow bishop described Hughes as "emphatically a self-made man." Born in 1797, his father owned a small farm in County Tyrone. From childhood he wanted to be a priest, but economic hardship forced him to leave school at an early age. At 20, he sailed for America. Over the next few years he worked as a day laborer in Pennsylvania and Maryland, doing construction jobs, digging in quarries, and gardening.

While he was working at a convent in Emmitsburg, Maryland, he met Mother Elizabeth Seton. Later as he worked on the grounds of nearby Mount St. Mary's Seminary, he rediscovered his vocation. But when he applied for admission, the president, Father John Dubois, rejected him. Mother Seton interceded for him, and he entered in 1820. Hughes always venerated her memory, but he never forgave Dubois.

Ordained in 1826, he was sent to Philadelphia. At St. Mary's, the city's most affluent parish, a struggle was taking place between the bishop and the trustees, who refused to relinquish control. Not long after being assigned there, Hughes told shocked parishioners that since they weren't observing their obligations, he wasn't interested in being their pastor, and he resigned on the spot. To put it simply, Hughes loved a good fight. One priest commented, "He is always game."

Through newspaper articles and public debates with Protestant ministers, he achieved national renown as a powerful Catholic spokesman. Bishop Henry Conwell of Philadelphia said: "Ah, that Hughes. We'll make him a bishop someday." It happened in 1838. He was sent to New York to assist Bishop John Dubois. At the time, as his biographer writes:

His personal appearance was striking and agreeable. He was about five feet nine inches in height, well formed, with a powerful frame, and, in early and middle life, an erect carriage. He had a remarkably large head, prominent features, a large but well-shaped Roman nose, a sharp resolute mouth, and brown hair . . . Until age and disease had set their mark upon him he was a handsome man.

Frail and aging, Dubois was ill-equipped to lead a growing Church, and Hughes took charge long before it was official. For over twenty-five years, he shaped Catholic life in New York like no bishop before him. Bishops preface their signature with a cross, but Hughes' opponents claimed that his was actually a dagger. Among the first to feel his wrath was the Public School Society, a Protestant organization running the city schools.

Public school days began with Protestant prayers, hymns, and Bible readings. Textbooks referred to Rome's "general corruption," and libraries carried books calling the Irish "drunken and depraved." Hughes argued that since the schools were essentially Protestant, Catholics should also receive public money. Appealing in vain to the usually pro-immigrant Democrats for help, he organized a political ticket that cost them votes at the polls. Catholic schools got no funding, but a bill was soon passed banning religion in public schools, thereby putting an end to the Public School Society.

As immigration from famine-stricken Ireland rose, hostility grew among native-born Protestants who resented their arrival. After they burned several Philadelphia churches, Hughes visited New York's mayor, who asked, "Are you afraid that some of your churches will be burned?" "No, sir," he replied, "but I am afraid some of yours will be burned. We can protect our own. I come to warn you for own good." Catholics citywide armed to protect their parishes. No churches were burned.

As the Catholic population increased rapidly, New York was named an archdiocese, and Hughes an archbishop. Many of today's parishes, schools, and charitable institutions have roots in his time. His statue stands on the grounds of Fordham University, which he founded in 1841 as St. John's College. In August 1858, he laid the cornerstone for a new cathedral uptown on Fifth Avenue and Fiftieth Street. Located far from what was then the city's center, it was called "Hughes' folly."