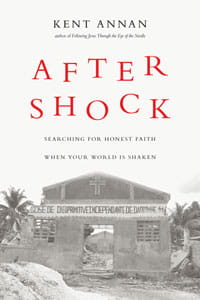

Editors Note: Taken from After Shock: Searching for Honest Faith When Your World Is Shaken by Kent Annan.

***

How long will you hide your face from me?

How long will you hide your face from me?

PSALM 13:1

For a few weeks when i was in my early twenties I wouldn't let myself stand on the balcony because I thought I might jump. I was staying with friends in the little town of Traiskirchen, Austria. The nearby tire factory dusted everything on the balcony and inside with black soot (little bits of rubber?), presumably including one's lungs.

A year out of college, I was working for a refugee ministry in Western Europe. I was sleeping on the living room floor. I was following the sinful saint through Frederick Buechner's Book of Bebb novels. At the nearby ice cream store, I flirted with a cute server as best I could in broken English and German ("Ein eis bitte"). My job was interesting and meaningful. I was lonely at times, but not unusually so. yet during those few weeks, I had to forbid myself from going out on the balcony when I was alone.

The discomfort was uncertainty. The tempter was, well, certainty. I wasn't in acute psychic pain or heavy depression. I just wanted to know. I needed to know. (I also remember at that time desperately wanting to be "understood," so maybe they're related, the need to know and be known.) It's hard not to laugh a little at myself with the vastness of what I wanted clear, certain answers to:

What is true?

Does life go on after death—and if so, on precisely what basis will we be judged?

Really, how can sexual intimacy be reserved for marriage, which in our culture does not usually happen till well into our twenties or thirties, and masturbation not be biblically encouraged? (Okay, this wasn't one of the existential questions, but there was a very fit couple in the apartment across the square from the balcony whose athletic, silhouetted lovemaking was hard to miss some evenings.)

God, are you there? I need to know.

Jumping would have been misguided, but I was longing for God, for love, for assurances. I miss that sense of longing these days; for all its desperation, there was a purity to it that is missing in the cold-war distance I feel lately—the occasional détente notwithstanding.

***

Many people, when God's goodness comes into question, think of God in one of two ways:

1. The Benefit-of-the-Doubt God

This is the God presumed by pop culture and promised, in its worst form, by the prosperity gospel. Professed by proof-texting and a secret belief in positive-only karma, this God wants wealth and goodness and happy endings. Essentially, God is the director of life's romantic comedy—inserting plot conflict to keep it interesting and to give characters opportunity for personal growth, but pulling strings so the ending is ultimately redemptive in this life.

When the plot goes really wrong, then it's our fault, not God's; we don't believe enough or aren't good enough. If we find we can't blame ourselves, we console ourselves that it's only a movie; the divine reality is yet to come. Hope and faith come at the cost of truth.

There are of course other, better versions of this. Actually, most of the devout Haitians I know think this way, even after the earthquake. The friends I talked with about these questions were still in worship, still devout, seeing the earthquake as a problem of nature and not a problem of God.

2. The Guilty-till-Proven-Innocent God

This approach says God is on trial for the sufferings of this world—and the verdict is not promising. Goodness and beauty do not balance out the horrors. Or at the very least it's a draw. Those who view God this way consider benefit-of-the-doubt believers naive. What kind of good Creator could possibly survive when 230,001 people don't survive under the created order (and human-created conditions) that just crashed on them?

One of novelist dostoyevsky's characters in The Brothers Karamazov doesn't shy away from putting God on trial. He famously details the suffering of a boy and girl and concludes that he will respectfully return his ticket (to life) back to God—because even all the goodness of the world cannot be justified by the horrific suffering of one innocent child.

These two options aren't a rubric for understanding how every-one approaches the problem of evil-good. But when I vacillate, it's often between these two stances, which are both related to uncertainty. We have to (by faith, one way or another) try to make sense of so much good and so much evil—and what this says about God.