Editor's Note: Below is a "Monday Sermon," our attempt at Patheos' Preachers Portal to provide sermons that pastors can enjoy and learn from. It is our hope that this particular series from Daniel Harrell, which preaches through the Church Fathers, will encourage pastors, show them a way of approaching theological education from the pulpit, and refresh their theological memories.

See Reverend Harrell's columnist page for more information.

Hailing from the 12th century, Bernard of Clairvaux was a prolific writer, preacher, and mystic whose works included a host of polemical treatises, letters, and hymns such as "O Sacred Head Now Wounded" and "Jesus, the Very Thought of Thee." His sermons remain popular devotional reading even today, especially those preached from the Song of Songs, that erotic little 117 verse book nestled in the middle of the Old Testament which also happened to be Bernard's favorite.

Hailing from the 12th century, Bernard of Clairvaux was a prolific writer, preacher, and mystic whose works included a host of polemical treatises, letters, and hymns such as "O Sacred Head Now Wounded" and "Jesus, the Very Thought of Thee." His sermons remain popular devotional reading even today, especially those preached from the Song of Songs, that erotic little 117 verse book nestled in the middle of the Old Testament which also happened to be Bernard's favorite.

Song of Songs is basically a collection of ancient Hebrew poetry celebrating wedded sexual love in all of its ecstasy, beauty, power, agony, and joy. As a celibate monk, Bernard presumably didn't have a lot of firsthand experience in this arena, at least not physiologically speaking. However spiritually (and thus more sublimely) speaking, Bernard was a seasoned lover. An ardent follower of Christ, Bernard insisted that Song of Songs was really a song about the mutual exchange of amorous devotion and desire between the King of kings and his Bride, the church. He dedicated eight sermons to chapter 1, verse 2 alone where the enraptured young beloved exclaims, "Let him kiss me with the kisses of his mouth—for your love is more delightful than wine." Eight sermons, Bernard preached, all on kissing.

I remember my first kiss. I was in sixth grade and Josie Fletcher invited a bunch of us over to her house one night to play "spin the bottle." Now I'm taking for granted (this being a wholesome website) that most of you aren't familiar with this spicy pre-pubescent party game. I know I wasn't. All I know is that suddenly I was sitting in this circle of hyper kids taking turns whirling a Coke bottle. Whenever it stopped, the spinner started smooching whomever the bottle pointed toward. It was pretty disgusting. I tried to graciously excuse myself (faking a cold), but the peer pressure made it abundantly clear that this evening devoted to swapping salvia was my pathway to elementary school panache. So I caved. However, on my turn I did give the bottle a pretty vicious spin. I think I was hoping I could override inertia and avoid the inevitable. But the bottle stopped on Jennifer Blake. I could have done worse. Jennifer was a looker. But she was also a seventh grader, which meant that she knew stuff. As it turned out, she was to be my teacher. She asked what kind of kiss I preferred. I thought, "What kind? I didn't know there were kinds!" She offered two. Regular and then something of a more Parisian variety. Figuring "regular" was the kind my mom gave me—and having heard interesting things about France from Social Studies class—I opted for the latter type and braced myself to be completely grossed out. But instead, I resurfaced from Jennifer's French lesson all loopy. Sacré bleu! Il était fantastique! Whatever aversion I previously held to kissing before that moment mysteriously dissipated.

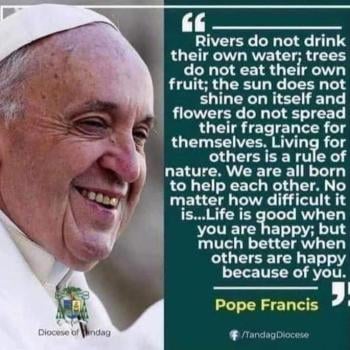

Bernard believed that such loopiness should actually accompany our relationship with Jesus. The French are a particularly passionate people. Bernard of Clairvaux was born in France in 1090 to aristocratic landowners, the third of six children. His reportedly model family and upbringing engendered in him a deep respect for mercy, justice, loyalty, and affection. Though his four brothers trained to be soldiers, Bernard set his sights on the intellectual life and had good prospects of success as a secular scholar. But rather than pursuing these prospects, he became convinced of a call to monastic life. After much prayer for guidance, he decided at age 22 to enter a monastery. This would have been nothing out of the ordinary in those days had Bernard chosen to join one of the rich and powerful Benedictine orders (named for last week's church father). His cerebral acumen and family connections would have assured him a long and distinguished clerical career.

However, to the shock and dismay of most, he decided against the moderate Benedictines and entered instead an obscure, austere community founded by a group of enthusiasts who wanted to live according to the letter rather than merely the spirit of St. Benedict's Rule. Bernard's family was horrified by this, considering it madness for such a sickly (Bernard suffered from migraines and gastritis his whole life) and sophisticated young man to join this harsh, demanding community, later to be known as the Cistercians. Moreover, when Bernard enlisted, the monastery was on the skids, waning rapidly due to a lack of recruits. Yet Bernard ended up turning it all around, eventually persuading his uncle, all his brothers, and most of his friends to join up as well. By the time of his death at age 63, Bernard had established sixty new Cistercian monasteries.