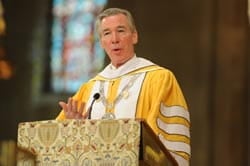

John Garvey, former Dean of Boston College Law School, was installed as the new president of Catholic University of America (CUA) last week. He delivered an inaugural address that in my mind captures a stunning vision of what CUA—and indeed, any Catholic university—can aspire to be.

John Garvey, former Dean of Boston College Law School, was installed as the new president of Catholic University of America (CUA) last week. He delivered an inaugural address that in my mind captures a stunning vision of what CUA—and indeed, any Catholic university—can aspire to be.

Full disclosure: John and I worked together on a committee at Boston College that addressed the Catholic intellectual tradition. I valued his always thoughtful contributions to that conversation, and was delighted to learn of his new position.

I'll mention two significant points in his address, but I encourage anyone to read the whole thing.

First, observing the landscape of higher education in the United States, Garvey says the following:

The mixed or secular model of education is the norm in America. In public schools we say the Constitution requires it. In private schools, where the first amendment does not apply, faith is unwelcome for epistemological reasons. Whether it is emotion or fantasy or paranormal perception, it is (we suppose) different from serious thinking—a distraction at best; probably misleading.

He is right, and he is pointing to a fundamental bias in the U.S. academy. The trajectory of modernity saw a naïve critique of the epistemological foundations of Christian faith: something along the order of "you can't measure it, so it must be false." That critique was checked off a list, as if the problem were solved, and further modern/postmodern conversations have really seldom looked back.

Today one sees continuing critiques of Christian faith (when academics deign to be concerned about it) rooted in this basic modern posture—even while theologians (myself included) object that the critique is naive and has not caught up to more robust postmodern foundations of theological conversation. (That's why we get irritated, not threatened, by the likes of the new atheists, who in my experience are just more recent and less creative versions of the old ones.)

There is a postmodern turn to religion with the likes of philosophers like Jacques Derrida, John Caputo, René Girard, Charles Taylor, and my Boston College colleague Richard Kearney, all of whose approaches to questions of faith are beyond the scope of the modern critique. To use one example, Charles Taylor's book A Secular Age, winner of the 2007 Templeton Prize, captures the problem facing the modern university in its uncritical embrace of secularism. I quote below a description of his book in an article by John Patrick Diggins in the New York Times:

[Taylor] argues for "the 'deconstruction' of the death of God view" proclaimed by Nietzsche. To see secularization as simply the separation of church and state, the alienation of truth from power, and the rise of skepticism and worldliness, he writes, is to miss the deeper and more enduring residues of religion and the spiritual life, the true "bulwarks of belief" that in his view have hardly eroded. Taylor argues against the "subtraction stories" of modernity, in which religious belief and other "confining horizons" are "sloughed off," leaving the mind without faith or piety. Instead, he argues, "Western modernity, including its secularity, is the fruit of new inventions, newly constructed self-understandings and related practices, and can't be explained in terms of perennial features of human life." Even the old distinction between the sacred and the profane has taken on new meaning. Instead of disappearing, God is now "sanctifying us everywhere," including "in ordinary life, our work, in marriage, and so on."

Catholic intellectuals have intuited Taylor's argument for some time, and Catholic universities, in my experience, retain vestiges of a basic conviction that people can find God in life, work, marriage, and so on.

Here, then, is Garvey's point: a Catholic university can be a better university than the average modern one, because it can open up critical space for entering into robust conversation about the implications of the epistemological foundations of modernity and postmodernity. Catholic universities aren't afraid of God—theophobes. They can be willing to probe the most foundational questions about human beings, human society, the cosmos, and the meaning of it all. Modern universities are good at the first three but not the fourth. They'll teach you how to get a job and maybe make some art, but can't really help you figure out why you're alive.