Film scholars have long remarked on the unexpectedly straight-forward and morally upright endings of many noir films, speculating that the Hays Code's insistence on the victory of virtue over cynicism may have been to blame—an accusation which, if true, produced some of the most iconic endings in cinematic history: Walter Neff speaking his halting confession into a detective's tape recorder; Joe Gillis floating face-down in Norma Desmond's swimming pool; Harry Lyme reaching up from the Vienna sewers with his last breath.

In Scarlet Street, however, such a memorable moment of justice and moral triumph is conspicuously absent. Lang takes great pains to convince his audience that there is no possible way that Cross will ever suffer publically for his crimes, despite his eventual efforts to admit to them. So thoroughly did Cross he succeed in convincing the police of his innocence (and sending Johnny to the chair) that his attempts to square the scales of justice fall on deaf ears.

The film's final shot, with Cross shuffling woefully past the art gallery where his final masterpiece has just been sold, gives audiences a glimpse of his future—a future haunted by the clamorous imputations of his victims. He, like so many of us, has managed to avoid the public consequences of his sins, but he will spend the rest of his days confronting the one jury he cannot possibly escape: himself.

While the bleakness of the film's finale is undeniable, it leaves behind a glimmer of hope, challenging the viewer to move beyond Cross' guilt-ridden desperation, to focus upon the possibility of his redemption.

Despite his unconscionable actions, Christopher Cross is a good man; as a good man, his future will be ever-clouded by the memory of the violence he has committed. Yet this memory may prove to be his saving grace, for it is an undeniable sign his conscience is working on him, reminding him at every turn of his heinous crime. In the daily struggle to appease the accusations of his conscience, he may finally work out his salvation, purified by the justice of his self-recriminations, and sanctified through the injustice of escaping unpunished in the face of such overwhelming guilt.

Cross is doomed (and blessed) to live out his name, carrying the cross of his transgressions until the end of his earthly days.

As one of the film's characters tells Cross, "Nobody gets away with murder. No one escapes punishment."

That is true for all sin, and thank God for it. But let us be even more grateful for the role we ourselves are allowed to play in the drama of redemption, and the conscience plays such an active part in the working-out of our own salvation. God, in His infinite Wisdom, makes use of our own self-knowledge and guilt to prepare us for His grace, saving us through the poundings of our tell-tale hearts.

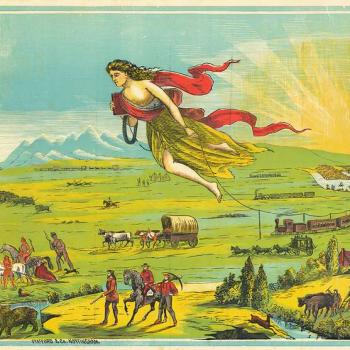

And Miss Film Noir is the surprising dame who can still be bothered to remind us of it.