Tucked into a residential neighborhood on a quiet Silver Spring, Maryland street is a house that has been converted into the temple of the Jain Society of Metropolitan Washington. Vari drives to temple every day. She prays and then she feeds the birds a twenty-pound sack of birdfeed. "Feeding the birds is a good thing to do—the birds are hungry, particularly in the winter," she says. A quarter of a mile away, a local elementary school serves, every other Sunday, as the Jain Religious School.

Tucked into a residential neighborhood on a quiet Silver Spring, Maryland street is a house that has been converted into the temple of the Jain Society of Metropolitan Washington. Vari drives to temple every day. She prays and then she feeds the birds a twenty-pound sack of birdfeed. "Feeding the birds is a good thing to do—the birds are hungry, particularly in the winter," she says. A quarter of a mile away, a local elementary school serves, every other Sunday, as the Jain Religious School.

Jain services are shockingly short to me, someone who is used to the three-hour Jewish Saturday Service. The service is no longer then ten minutes. Men and women stand separately on red carpets, topping a marble floor. The children are invited to the front, a candle is lit, there is singing, and then it is over.

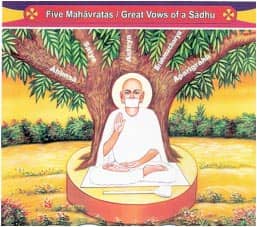

There are three idols in the temple room—two are from one sect, one from another; the sharing of a temple by different sects is unheard of in India, where the majority of Jains live. There are no prayer books or placards announcing the page of the next prayer. Throughout the day members walk into and out of the temple room, touching the idols, praying, or simply sitting in silence on the floor.

The idols are pale marble; the two representing one sect are ornately decorated and adorned with gold crowns; the third representing the other sect looks simpler—just the marble. All present are "in the know" but me, the only white person at the temple. At the entrance to the temple room a sign says "please keep door closed," in a largely failed attempt to provide quiet in the temple room as the rest of the building fills with comfortable chatter.

While the service is short, the day is long. It begins with religious school. I walk into the oldest class—six casually dressed teens are sitting in the multi-colored chairs of a preschool class, their teacher sitting in a similar chair. Their soft-covered, English language textbooks are open on the table. The teacher, a middle-aged man with an Indian accent, is telling the class that "the biggest challenge is doubt." He acknowledges the age of the texts and the difficulty of believing their authenticity, while at the same time demanding faith. "You should be beyond doubt," he says.

For my benefit, he asks a student to recite the "Three Jewels"—"Right knowledge, right faith, right actions." The class ends ten minutes early for the students to discuss their performance in the upcoming festival; this year's theme is "Jains Around the World." The class is representing Jains in China. The teacher warns them not to rely too heavily on martial arts. "Martial arts are aggressive, we want gentle."

Before the community started a religious school, there was Jain Camp. Kinjal, a young father of two elementary school boys reminisced about Jain Camp. Over a decade later he is still in touch with the majority of the other campers.

For two weeks at Jain camp we did yoga, played sports, learned about our history, our traditions, and met other Jain kids. In school I did not know too many Jains.

After school ends, we drive the quarter-mile to the temple. Everyone takes off their shoes and I also take off the leather cover on my notebook and abandon it along with my purse in the entryway. The entire wall is covered with shoe cubbies. Nearby, there are no-kill mousetraps, available for community use.

While the children are in religious school, so are the adults. In the adult classroom, men and women are sitting on separate sides of the room. A few people are sitting on chairs; most are sitting on the floor. The floor sitters are engaged in meditative prayer while listening to the class. The class is attended primarily by older adults; the parents of school-aged children are busy driving them to the temple at this time. The adult class is in Punjabi, a language spoken in North West India and Pakistan. There are two or three women wearing white cloth masks (which look almost like old-fashioned surgical masks) over their faces to prevent them from harming any "air beings." A little less than half of the women that day are wearing tradition Indian dress, mostly Shalwar kameez, a tunic-pants combination; the majority are wearing casual western clothing. Nikhil, an older member, discusses the rhythm of the community.

Children go to religious school, and are involved. But then they go off to college, and build their careers. When they have their own children they come back. That's when I came back.