As Lent begins, I find myself reading excerpts from the Autobiography of St. Teresa of Avila. Teresa writes about the life of prayer and the gifts His Majesty wishes to bestow, and remarks that some—by the mercies and pleasure of the Lord alone—manage to learn in an hour what takes others a lifetime. In her downright way, she makes a rueful acceptance of the fact that some of those she taught and counseled understood in weeks what she did not know after twenty years of prayer, and then Teresa helplessly, adoringly, praises God for doing His own will.

As Lent begins, I find myself reading excerpts from the Autobiography of St. Teresa of Avila. Teresa writes about the life of prayer and the gifts His Majesty wishes to bestow, and remarks that some—by the mercies and pleasure of the Lord alone—manage to learn in an hour what takes others a lifetime. In her downright way, she makes a rueful acceptance of the fact that some of those she taught and counseled understood in weeks what she did not know after twenty years of prayer, and then Teresa helplessly, adoringly, praises God for doing His own will.

I remembered Teresa's observation when I read this story of filmwriter Joe Eszterhas' dramatic conversion experience:

With serious habits of smoking (since age 12) and drinking (since age 14) plaguing him after a diagnosis of throat cancer in 2001, Eszterhas felt impending doom. Last year he recounted in the Washington Post's "On Faith" site about collapsing on the side of a street. "I cried and begged God to help me," he wrote, ". . . and He did. I hadn't prayed since I was a boy. I had made fun of God and those who loved God in my writings. And now, through my sobs, I heard myself asking God to help me . . . and from the moment I asked, He did."

He reported his throat doctor told him seven years after the surgery that I am "cured . . . That my throat tissue has regenerated so remarkably that even a doctor examining my throat wouldn't be able to tell that there was ever cancer there." The doctor, who had removed about eighty percent of the writer's larynx, called this "a miracle."

Eszterhas asked: "Why did God save the life of man who had trashed, lampooned, and marginalized Him most of his life? Why did He take the time and the trouble to save me?" It sure wasn't on account of his professional body of work. Quite the opposite. "His love is so strong that it was even able to open my rusty old closed heart."

"His love is so strong . . . " It makes all things new. It creates and recreates, it permeates, it builds and renews.

His love is so strong that it breaks through all of our barriers—the physical ones (how many women do you know who have gotten pregnant even while using birth control?) and the spiritual ones, and even the intellectual ones. Those intellectual barriers may well be the most fortified and resolute because they are mortared with pride (which is the Evil's handiest tool) and then fed on hurt and fear (Evil's fruitful gardens).

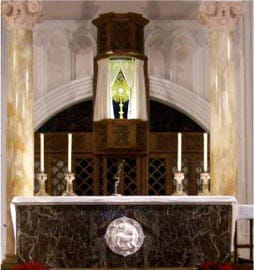

"His love is so strong . . . " I read it and my eyes grow moist. Yes. I know it. On my last monastic retreat, where the Blessed Sacrament was in perpetual exposition and I was privileged to spend as much time before the Real Presence as my heart could stand, I made a point of keeping watch in the wee small hours. At one point, as I lay prostrate before Him, I got the merest glimpse of the strength Eszterhas describes above. His love radiated down from what my human eyes perceived to be a piece of bread, what my heart and spirit knew to be so much more, and for a brief time it bathed me in the warmest, most caressing Light, and everything became different. Nothing since then has been what it was. In the Light, the shadows and illusions fall away and you stand in the only Reality, the Completeness, the All-in-All. There is nothing else.

It was such a moment, such a glimpse, and yet I am still so wretchedly connected to this world, this earth, this thing, this me—still so entwined in my faults which are like clinging vines, ever dragging me down and back to where I would rather not be. I cannot even begin to write it; I haven't the words, myself, so you, Lord, will have to help me because I am helpless. I am still processing this Tumbledown Love, which has been so ruinous to all of my comfortable certainties, and is still taking me apart, brick by stubborn brick. I am still needing prayer and prayer, and prayer.

Not long ago, I got an email from a Catholic cleric who had just been dealt a humiliation by a very thoughtless pastor. In his angry, frustrated state, he went to the church, where he had the immense privilege of officiating at Benediction. That means that at the end of the Exposition of the Blessed Sacrament, he donned the humeral veil (explained beautifully here) and raised the monstrance containing the Host—where Christ is Present, under the appearance of bread. With the monstrance he then made the Sign of the Cross over the congregation. He assisted Christ in making this powerful blessing. How does one assist in the blessing of the faithful; hold Him in one's hands and not feel inclined to bash all anger, all fear, all frustration, temptation, hopelessness, upon the cross of Christ—which can bear all things—and simply consent; simply allow Him to recreate, revive, restore to make everything, everything, new?