Of Gods and Men is the greatest film on faith I've ever seen. It surpasses even some of my longtime favorite movies on the spiritual life, like Romero, Diary of a Country Priest, A Man for All Seasons, The Mission, and The Song of Bernadette. Perhaps only Franco Zeffirelli's multi-part series Jesus of Nazareth has moved me more.

Of Gods and Men is the greatest film on faith I've ever seen. It surpasses even some of my longtime favorite movies on the spiritual life, like Romero, Diary of a Country Priest, A Man for All Seasons, The Mission, and The Song of Bernadette. Perhaps only Franco Zeffirelli's multi-part series Jesus of Nazareth has moved me more.

By now, you probably know that the French-language movie, lauded in all corners (except, inexplicably, by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences—the film was omitted from being nominated for Best Foreign Language Film), is about the Trappist monks of Our Lady of Atlas Monastery in Algeria, who were assassinated by Algerian extremists in 1996. Their story, which was in danger of being forgotten even in many corners of the Catholic world, is told in John Kiser's essential book, The Monks of Tibhirine.

What may make the film so profound?

First of all, it is a realistic portrayal of the life of faith. The monks are not perfect; no saint, or martyr, is. Holiness always makes its home in humanity. Occasionally the monks are impatient, tetchy, or short with one another. ("He's tired," says an older monk after a younger one has spoken to him sharply while cleaning up after a meal.) One of them thinks wistfully of the life that he might have had "on the outside." Moreover, the group struggles mightily with the idea that they might be "called" to be martyrs, indeed resisting it until almost the last minute. As anyone would. The life of the believer often involves uncertainty, doubt, and confusion. Two of them are seen, quite distinctly, as "avoiding" their fate. But all try to grapple with what God seems to be asking of them, strange and frightening as it may seem to them.

Second, the movie does not stint—at all—on the religious underpinnings of their actions and choices. Too often in contemporary cinema, producers or directors indicate by their own choices that audiences will not understand people who talk about God in a serious way. And so we see (and hear) the monks chanting their prayers, celebrating Mass, preparing for Christmas. In this way the movie was reminiscent of another recent film on the monastic life, the documentary Into Great Silence. We hear the words of their prayers, too; and we are privy to their conversations with one another about God, and often with God. God is real to them; and God's effect on their lives is made real to the viewer.

We see, too, the real-life effects of their Christian faith: particularly in the love they show (and receive) from the villagers who live near the monastery. The Trappists are, moreover, charitable and loving not only to friends (to one another; to their longtime friends in the village), but to those who oppose them (to both the terrorists who threaten their lives and the army officers who have nothing but contempt for their desire to stay). The life of contemplation and action are inseparable; the true effects of their belief are made manifest.

Third, the director Xavier Beauvois underplays many scenes, like a beautifully pastoral image of the abbot walking silently through a flock of sheep. Another director might have wanted to demonstrate more explicitly (through music, a caption, or a voice-over) the idea of the Good Shepherd who does not leave his flock, which the monks discuss at one point during their deliberations on whether or not to "stay." The use of music from "Swan Lake," which Anthony Lane in the New Yorker felt was used more effectively than even in Black Swan, is also subtle. At a meal, a kind of Last Supper before their martyrdom, the community listens not to the traditional "reading at table" (where a monk reads from a religious text to the silent diners), but to Tchaikovsky's great music. They drink good wine, as the camera pans over their now confused, now calm, now sorrowful, now joyful faces.

The movie, as the modernist poets liked to say, shows rather than tells.

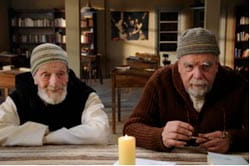

Fourth, the actors' performances are nearly perfect. Based on the monks (and Trappists) I know, these characters felt as close to real monks as I've ever seen on screen, particularly the kind-hearted Brother Luc, played by Michael Lonsdale, and the intellectually-minded abbot, Christian, played by Lambert Wilson (who can be heard here on NPR's "Fresh Air" speaking about his role).

Fifth, and perhaps most importantly, the film treats the idea of martyrdom intelligently. Watching Of Gods and Men, I started to realize, slowly at first then more strongly, that more people might begin to understand the strange idea of martyrdom. For it is an idea that even believers find hard to comprehend.