The April 8 anniversary of the funeral of Pope John Paul II recalls a question asked of a Catholic writer by an Evangelical Christian: Why wasn't the pope buried in a simple shroud, like Jesus? The email goes on to ask:

The April 8 anniversary of the funeral of Pope John Paul II recalls a question asked of a Catholic writer by an Evangelical Christian: Why wasn't the pope buried in a simple shroud, like Jesus? The email goes on to ask:

I'm asking this because I think you will answer me respectfully. The service today was beautiful but wasn't it too much? Jesus was buried in a simple shroud, and he was God. What we saw today bordered on idolatry. I have no problems with Catholics, I do believe you are Christians, but I think you are misguided on this.

I am not sure it makes any sense at all to compare the burial of Pope John Paul II to the burial of Jesus.

Jesus was buried in the manner of a wealthy man of his time—in a private cave hewn for that purpose and originally purchased by Joseph of Arimathea—so it could be argued that outside of pyramids and kings' tombs, Jesus' burial arrangements (though rushed for Passover) were slightly better than average. He was wrapped in a shroud because that's what was done, and is still done in that part of the world.

Currently, the average American citizen who dies has a wake, then a funeral service, flowers, an expensive casket, pall bearers with dignified bearing, readings, grieving, and usually a supper to follow—a celebration of that person's life. All in all, a much more elaborate burial than Jesus, who was (is) God. Times and customs and cultures do have an effect on things. If a beloved family member of yours dies, are you going to limit his or her burial to a shroud and a howdy-do, because that's all Jesus got?

Remember, when Jesus was buried, his apostles didn't know he was God. They thought he was a prophet. They'd thought maybe he was the messiah, but then, you know—things didn't work out as people expected; he was tortured and killed and his followers went into hiding. They didn't know what-and-whom they had, among them, until later. Had they known, there might have been quite a different send-off!

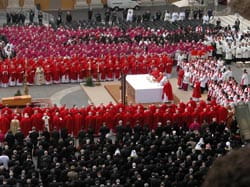

The Holy Mass you saw broadcast to the world—beautifully sung, beautifully carried out, calling on the prayers of the great Cloud of Witnesses who have gone before us—was not exclusively for John Paul. Yes, it praised and worshiped God, and it commended His Holiness to heaven while celebrating his faithfulness, but the liturgy was meant in part, for us. We are not machines, but humans, and when something important happens, as the loss of a loved one, our hearts hunger for meaning, but also for beauty, which is another transcendent means to God.

Millions traveled to Rome to prayerfully, lovingly see off a servant of Christ, and for their efforts, they saw beauty, they heard and felt beauty, they had the opportunity to pay their own tribute ("Sancto!") and, most importantly, they got to participate in the communion of faith, and to commune personally with the Lord Jesus Christ in the Blessed Sacrament.

The people kneeling on the cobblestone of St. Peter's Basilica were not kneeling for Pope John Paul II; they were kneeling while Communing with the Lord.

Liturgy does not only instruct; it also entertains, by engaging mind, soul, and senses in a way that moves us forward with interest and curiosity, until it enables understanding to become transcendent. The writer Rumer Godden put it more succinctly: "the blessing of the liturgy," she wrote, "is that it wipes out self."

If you belong to an Evangelical church, you probably have musicians and singers at your service, and if the music they provide is uplifting, it brings another dimension to worship. Just so with the liturgy, and with all of that pomp you found disturbing. Far from being idolatry in the name of Pope John Paul II, it was the vehicle used for the delivery of our uplifted hearts to Christ. John Paul didn't care; he was already in heaven!

Our beloved pope was remembered with love. He was dressed in fine robes (when we buried Grandma we put her in her best dress—what else?). His casket was incensed, because incense reflects our Judaic heritage, it echoes the psalmist: "let our prayers rise like incense." The angel in Revelation dispenses cleansing incense pretty liberally, so God would seem to like it. Then, after the mass, his body was solemnly processed and laid to rest.

It is all we would do for any of our loved ones, just on a scale calculated to uplift not just thirty or forty mourners, but a couple billion.

Perhaps you were troubled by the crowds chanting "Sancto! Sancto," and that is what seemed idolatrous to you, but consider this: at my son's high school, one of the athletes died, tragically, of cancer. The funeral convoy drove past the school, and all of the students had assembled outside. They stood solemnly and then applauded and waved to the hearse and to his parents, shouting his name, his team number—they shouted "we miss him!" and "your son was great!" loud enough for the parents to hear it. Was that idolatry, or a simple, heartfelt last opportunity to praise a much-loved fellow?