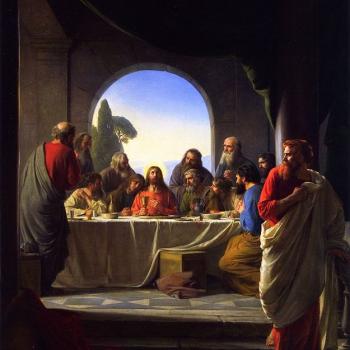

On Sunday I went to visit the Passion in Venice exhibit at the Museum of Biblical Art in New York City (NY Times review here). The exhibit captures a key theme from late medieval piety that speaks with remarkable clarity to the world we live in today: namely, the figure of Christ as the Man of Sorrows. This theme calls to mind with great poignancy the truth that the brief span of human life involves suffering, and affirms the central Christian belief that when God walked among us he was not exempt from it.

The exhibit focuses on key Venetian artists, especially Veronese, but its span is wider. It highlights the fact that artists of the 14th century began bringing attention to this theme, in part because new trade routes with Constantinople made possible their encounter with more Byzantine art.

The Man of Sorrows theme is rooted in a text from the book of the prophet Isaiah, in a section known as the song of the suffering servant:

He was despised and rejected by men;

a man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief;

and as one from whom men hide their faces

he was despised, and we esteemed him not (Is. 53:3 RSV).

One can surmise that the particular attraction to this theme might have been related to the experience of the Bubonic plague—the Black Death—which over a period of two years (1348-1350) wiped out as much as half of the population of Europe. Amidst such a constant reminder of suffering and death, it is no surprise that artists would search for answers to basic philosophical questions about life.

Venice was a city under the patronage of St. Mark the Evangelist, whose gospel carries a particular resonance with the Man of Sorrows theme. Mark's gospel is a series of short vignettes about Jesus' life and work, followed by an extended passion narrative that ends with Jesus' death and then a mysterious empty tomb. The feel of Mark's gospel is that of a martyr story, with a sliver of hope at the end. Mark's gospel does not have the triumphant feel of John, the epoch-making historical proclamation of Matthew, or the missionary fervor of Luke. Instead, Mark's story is about the reality of Christ's suffering, a story which no doubt gave comfort to the disciples who themselves felt the fear of persecution under cruel Roman emperors like Nero and, later, Domitian. The passion narrative, like the Man of Sorrows theme, is a reassurance to those whose suffering is real and whose questions are persistent: why must I suffer? why me? why this way? why must it hurt so much?—the reassurance that in suffering, they are not alone.

There is a story told in the Buddhist tradition that functions in a manner similar to that of the Man of Sorrows. In the story, a woman whose only child died of sickness was deserted by her husband. She came to the Buddha in the hope that he would relieve her pain by giving life to her son. He told her to find a family that had not known death, and ask from that family a mustard seed with which he would revive the child. The woman, unable to find a family that did not know death, came to understand that suffering and death are inevitable.

During Lent, many Catholics meditate upon the passion and death of Jesus, with devotions such as the sorrowful mysteries of the rosary and the Stations of the Cross. Some may consider these devotions morbid, as if dwelling on suffering and death is pathological. Yet what becomes evident in the Museum's exhibit is that meditating on suffering and death is dramatically life-embracing. Ours is a culture that fears death and tries at all costs to keep it at bay: we "fight" diseases and "beat" illnesses. Our best scientists "team up" against pandemics like AIDS or malaria. And to be sure, we live in a world in which we are less prone to the kinds of miseries that plagued (literally) our ancestors. Yet the perennial truth is that suffering and death still happen to every human being, and our collective efforts to tame and isolate them are ultimately futile. We will not get out alive.

There is, moreover, a dark side to our attitudes toward suffering and death: we are terrified of them when they actually happen to us or to those whom we love. We shout out with existential angst at the unfairness of the universe, and often curse and reject God for subjecting us to pain. But the Man of Sorrows beckons: yes, suffering and death are real and they hurt, but they are part of the human condition and Jesus himself chose to accept them. His experience in Gethsemane, his feeling of total alienation from God, are no less real than our own. The artistic images of his broken, bleeding body call to the viewer to pay attention—not in a pathological way, but a realistic one. And what they say is this: do not be afraid. Even God lived through the implications of this seemingly unfair world he created. But like the mother giving birth, he has taken on the pain out of great love because he trusts that there is great good to come of it.