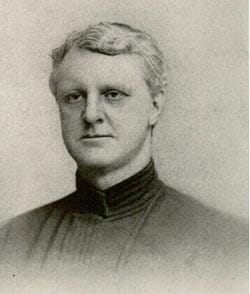

As Christians celebrate Jesus' Passion, death, and Resurrection, this week's column focuses on a religious community dedicated to proclaiming "Christ's crucified love." During the Passionists' early years in America, one of their preeminent figures was James Kent Stone (1840-1921). Before age 30, he had been a Harvard graduate, Civil War veteran, minister, professor, and president of two colleges. One Passionist historian refers to him as "this illustrious man."

As Christians celebrate Jesus' Passion, death, and Resurrection, this week's column focuses on a religious community dedicated to proclaiming "Christ's crucified love." During the Passionists' early years in America, one of their preeminent figures was James Kent Stone (1840-1921). Before age 30, he had been a Harvard graduate, Civil War veteran, minister, professor, and president of two colleges. One Passionist historian refers to him as "this illustrious man."

He was named for his maternal grandfather, one of America's foremost legal minds. His father was an Episcopal priest, whom Daniel Webster considered the best preacher of his time. Kent (as he was familiarly known) attended private school and later Harvard, where friends included Oliver Wendell Holmes. After graduation in 1861, he studied abroad in Europe, but returned to fight in the Civil War.

A Lieutenant in the Second Massachusetts Infantry, he fought in the Battle of Antietam, the war's single bloodiest day. By the end of 1862, a severe hernia ended his army days and he took a teaching position at Kenyon College, an Episcopal school in Ohio. That summer he married Cornelia Fay. They would have three daughters. In 1867, at 27, he was named President of Kenyon. He was also ordained.

At the time, Episcopalians were split between between "Low Church" adherents, leaning toward Evangelical Protestantism, and "High Church" followers, emphasizing ritual and tradition. Kenyon was predominantly Low Church. The local bishop felt Stone's sermons were too High Church. After heated controversy, he resigned in 1868, but was soon named President of New York's Hobart College, a High Church school.

At first, he saw Episcopalianism as a middle way between what he considered Puritan and Roman extremes. Raised in a strongly anti-Catholic atmosphere, Stone one morning woke up with a thought: "What if the old Roman Church should be right after all?" Such a notion, he added, had previously "never entered my mind." When Pope Pius IX invited Protestant leaders to reconsider their theological basis, Stone responded. In 1869, he resigned both from the college and the ministry.

That December, he was received into the Catholic Church. He discussed his reasons in a book titled The Invitation Heeded. Catholicism alone offered "safety for the soul and healing for the nations." To those citing corruption, he responded: "There are scandals . . . if we look for them. But there have been saints and martyrs . . . of whom the world knows nothing. And there are saints still." While his parents didn't reject him, a cousin labeled him "the weak-minded one of the family."

During this period, Stone's wife died. Most such-situated widowers saw themselves as having two choices: remarry or send the children elsewhere. He had his daughters baptized Catholic and placed with a family he knew in California. But it wasn't an easy choice, and it tortured him for decades. Years later as a priest, when a little girl ran up to him and hugged him, the normally cool and collected father and widower broke down in tears.

After his conversion, Stone was offered a teaching position at Georgetown, but he wanted to continue his priestly ministry. He liked the Passionists, with whom he made a retreat, but wasn't sure he could handle their austere lifestyle. George Searle, a Harvard friend, had joined the Paulists, a community composed predominantly of converts dedicated to evangelizing America. He suggested that Stone join them.

In 1872, James Kent Stone was ordained a Paulist priest. He was a successful preacher, but he still felt a pull toward the Passionists. In 1877, he finally joined, taking the name "Fidelis of the Cross." (In religious life, name changes symbolized a deeper interior change.) At 37 he started over once more. But what one saw most, peers noted, was his happiness.

The Passionists' main work was preaching missions, a weeklong series of talks and services designed to re-energize local Catholic life. (In many cases, these drew thousands.) Its ultimate goal, for St. Paul of the Cross, was "to teach people how to pray." Stone was one of their best preachers. A handsome man well into old age, he stood over six feet tall, with a winning smile and a well-modulated voice.

Felix Ward, a Passionist historian, writes: "As he stood on the platform beneath the large crucifix, in the Passionist habit, few could resist his appeals." He once preached in Baltimore to a crowd that included President Chester A. Arthur and members of his cabinet. Later he would preach at his alma mater, Harvard, one of the first Catholic priests to do so.