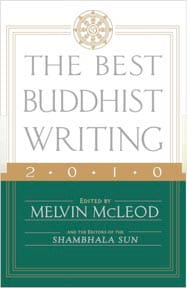

The Best Buddhist Writing 2010

The Best Buddhist Writing 2010

Melvin McLeod, editor

Shambhala Publications

304 pages, paper, $17.95

Eternity, Blake says, is in love with the productions of time. (And vice-versa!) Ultimately, truth has no beginning, middle, nor end. Yet it intertwines with the historical world. So each year I greet with great pleasure—and a divine delight—yet another new edition of The Best Buddhist Writing. And 2010, seventh in the series, is no exception.

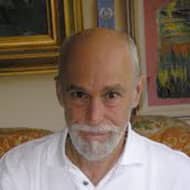

What constitutes "best" (and, for that matter, "writing" and "Buddhist")? In a brief interview with American Book Review, series editor Melvin McLeod outlined for us some defining traits:

Honesty—willingness to be honest about realities of life—is one characteristic I look for. Heart and compassion and sympathy for one's self and others. Realization is another. And a sense of beauty and elegance in writing.

If an anthology is a critical act, the Best Buddhist Writing exemplifies high standards. Along with an engaging range and meaningful depth of selection, Mr. McLeod's introductory briefing to each year's crop is invariably an integral pleasure of the book's occasion. He has worked in media for over thirty-five years, as editor of Shambhala Sun magazine since its inception in 1993. His writing and editing balance analytic rigor with warm, open-heartedness—a blend that typifies his Vajrayana Buddhist lineage. Call it citizen journalism, or spiritual journalism—he publishes what he practices.

So what's at hand for 2010? Editor McLeod locates this year as one whose global affairs continue to have been marked by religion. He then delineates Buddhism's uniqueness: nontheistic, concerned with mind rather than, say, First Cause or unsayable Name; no divine prophet, no sacred book. This gets to the bones of the Buddha's foundational teaching. To paraphrase the Jogger's Mantra: pain is inevitable, yet suffering is extra.

In these pages, you'll thus find accounts of diverse people variously coming to grips with pain and suffering, opening with Stan Goldberg's memoir of volunteering in a hospice shortly after his own diagnosis of prostate cancer. Zen priest Norman Fischer faces his grief at the death of his best friend, Rabbi Allan Lew. Jarvis Jay Masters writes from Death Row, on experiencing freedom.

Just by being aware of others' suffering and opening to others' experiences and insights we're invited to widen our own view. This also reminds us not to seek changeless, absolute truths (thank God). Rather, truth is in life itself.

Buddhism's practical antidote to needless suffering is exemplified here via the words of Sylvia Boorstein (on human solidarity), Pema Chödron (on vulnerability to pain as opportunity for growth), Gaylon Ferguson (on our natural wakefulness), Ven. Thich Nhat Hanh (in q&a with kids), Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche (on the art of awareness), and Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche (on finding joy amidst difficulties). Each offers us an awakening to a better way, always available to us, in the present moment. (When else?!) Whatever the insight, activity, or meditation offered, each author reminds us of the birthright of our inherent buddha nature, already within our reach.

In short, this latest installment in a worthy, noble, and most-welcome series offers, as ever, a nice blend of episodic detail and panoramic perspective, served up via a pleasantly eclectic mix of voices. Seeds, path, and fruit are all in clear view, depending on your level of engagement. And you don't have to be Buddhist to appreciate or derive benefit from any of it.

Besides looking at the book head-on—as to its contents—we might also turn it sideways, for contexts. Let's explore the publisher's carving a path for Buddhism in the West, and the impact it's having.

The Buddha ("The Awakened") was a realized teacher who, during his life, spoke directly to his students. The presence of living teachers is thus crucial. This writer recalls when more Eastern Buddhas were sitting out in museums, behind glass, than living, breathing ones. Consider the exiled Tibetan Buddhist teacher ("rinpoché") Chögyam Trungpa (1939-1987). One of his students, author Rick Fields, once recalled, "He caused more trouble and did more good than anybody I've ever known." The good well remains.