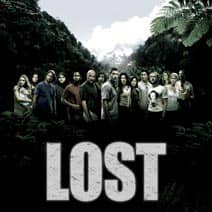

The ABC TV series "Lost" left the air almost a year ago, yet it continues to generate lots of emotion from fans and detractors. Recently the show's Executive Producers, Damon Lindelof and Carlton Cuse were blind-sided by insults from popular fantasy author George R.R. Martin, whose book Game of Thrones has been turned into an HBO mini-series, and who continues work on his Song of Fire and Ice book series.

The ABC TV series "Lost" left the air almost a year ago, yet it continues to generate lots of emotion from fans and detractors. Recently the show's Executive Producers, Damon Lindelof and Carlton Cuse were blind-sided by insults from popular fantasy author George R.R. Martin, whose book Game of Thrones has been turned into an HBO mini-series, and who continues work on his Song of Fire and Ice book series.

Martin expressed concern about finding a satisfying ending for his series saying, "What if I f--- it up at the end? What if I do a Lost?"

That comment struck Lindelof and Cuse as unnecessarily harsh; they had poured their hearts and souls into "Lost's" storytelling. Both men responded on Twitter—Lindelof with some zingers directed at Martin; Cuse more succinctly with the statement, "We never raise ourselves up by demeaning the work of others."

Having watched "Lost" from the beginning, I think the level of animosity directed at it is completely unwarranted. The show told a brilliant, engaging story in a way that made it matter to people. In fact, it's a story that I believe continues to matter.

For the uninitiated, "Lost" dealt with a group of plane crash survivors who landed on a mysterious, mystical island. Initially, these castaways were emotionally-crippled souls without any genuine human connections, but through the love and responsibility they exhibited toward each other, they were able to grow as human beings—to move past the tragedies, mistakes, and obsessions that haunted them and eventually arrive in a state of grace. Despite everything you may hear about the show's complicated mythology, these are the issues the show was about at its core.

Before the haters and naysayers chime in, I do acknowledge that "Lost's" mythology grew unwieldy, and numerous threads were not tied up. But to paraphrase Shakespeare, "Lost" is a show far more sinned against than sinning. It dared to deal with big issues—faith and doubt, sin and redemption, earthly life and the afterlife—through some of the most well-drawn and acted characters ever created on television.

Take the issues of faith and doubt: There was an ongoing clash between the characters Jack Shephard and John Locke about whether our actions and experiences in life have some unseen purpose, or whether only those things that can be scientifically proven and deduced are real.

In one heated exchange, Locke screams at Jack, "Why do you find it so hard to believe?" Jack responds, "Why do you find it so easy?" Locke exclaims, "It's never been easy!"

Right there, you've got an encapsulated version of questions that most believers of all stripes have grappled with. In a world where earthquakes and tsunamis kill thousands, where people who've made evil decisions live to a ripe old age while innocent children die in accidents or from diseases, there can seem like plenty of reasons not to believe in a benevolent God. Yet if people are humble enough to consider the possibility that a reality exists beyond what the senses can experience, they may come to notice connections and meanings they never knew were there. "Lost" did an excellent job of bringing those questions and struggles to light in a way that resonates with the open-minded.

Lost's themes about the journey from sin to redemption was reflected in all the primary characters, but none quite so well as Ben Linus. He was a Machiavellian villain who justified his own self-aggrandizing actions as being for the good of the island. As the story progressed, however, we began to see hints that he genuinely cared about his adopted daughter, Alex.

When she is murdered because he refused to give himself up, there's a change in him; the guilt of not saving Alex gnaws at him, slowly producing a change for the better. That change doesn't proceed in a straight line. Just when you think Ben is getting in touch with the better angels of his nature, he kills someone and is seemingly back to his old ways. There comes a point when Ben, who had allied himself with the good guys for a while, believes he has nowhere to turn but back to the story's chief villain in order to survive. What happens next is a perfect mirror for Catholics familiar with the sacrament of confession/reconciliation.

Ilana, who is the representative of the island's godlike figure Jacob, whom Ben had murdered, confronts him about what he did. Ben finally breaks down and admits, "I watched my daughter Alex die in front of me. And it was my fault. I had a chance to save her . . . I'm sorry I killed Jacob, I am, and I do not expect you to forgive me because I can never forgive myself." When Ilana asks Ben why he wants to now ally himself with the island's resident evil, Ben responds, "Because he's the only one that'll have me."