When taking days off for Jewish Holidays, more than one college professor asked me if I were Orthodox. My partner regularly wears a Kippah at work, and he is asked if he is Orthodox too. A person familiar with my writing on Judaism was so confident that I was Reform that he told others of my "affiliation." On Facebook, I am non-denominational; I identify as unidentified. Years ago, while interviewing for a Hebrew School job, with a secular humanist congregation, the principal of the school proudly explained that they are not a "flag-waving bunch."

When taking days off for Jewish Holidays, more than one college professor asked me if I were Orthodox. My partner regularly wears a Kippah at work, and he is asked if he is Orthodox too. A person familiar with my writing on Judaism was so confident that I was Reform that he told others of my "affiliation." On Facebook, I am non-denominational; I identify as unidentified. Years ago, while interviewing for a Hebrew School job, with a secular humanist congregation, the principal of the school proudly explained that they are not a "flag-waving bunch."

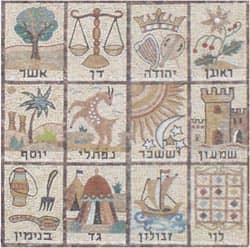

The Jews traveling through the desert (after leaving Egypt, before going into Israel) were a flag-waving bunch. Bamidbar, the fourth book in the Torah, opens by putting the Jews in their places. From a census, which begins the book, we get the book's English name, Numbers. The word Bamidbar, however, means wilderness, which is the primary setting of the narrative. It is in the wilderness that God tells Moses to conduct the census of the tribes and then to divide the tribes in their camping formation.

The children of Israel shall pitch by their fathers' houses; every man with his own standard, according to the ensigns; a good way off shall they pitch round about the tent of meeting (Num. 2:2).

In Bamidbar, there is no room for questions of affiliation; the physical space itself is demarcated. Each Jew in the desert camps under his tribal banner. Jobs in the tent of meeting, or the mishkan, are assigned to the tribe of Levi and further subdivided according to family. A Levite man born into the family of Gershon will camp behind the mishkan to the west and carry the coverings of the mishkan through the desert (Num. 3:21-26). A Levite born into the family of Kohath will carry the covered Ark, but if he ever sees the Ark uncovered he will die (Num. 4:17-2). Only the high priest was permitted to see the Ark and only on Yom Kippur.

A Midrash Rabbah, a collection of classical rabbinical exegesis, tells of the origins of the tribal flags. The Jews were inspired to make their flags after seeing the angels carrying flags at Sinai, when the Torah was given (Bamidbar Rabbah 2). In the Jewish tradition, angels do not have free will; they are created to fulfill a specific purpose. The angels' flags encapsulate their predestined lives. The Jews wanted to be like angels; they ached for the clean simplicity of destiny, the allure of waving flags in the empty desert. According to Midrash, Jews were the first nation to use flags.

I understand the desire to surrender to the flags, to be like angels, forever consumed with that for which you are created. The image of flags in the desert tempts me as it tempts the authors of Bamidbar Rabbah, who understood something about the connection between waving of flags, collective identity, and free will. There is peace in knowing where to set up camp in the wilderness. It can be a blessing.

Except for the children born to the wrong flag. Imagine a child born into the Kohath family, fervently and reverently wanting to see the holiest Ark—and knowing that, because he was born Kohath and not the son of the high priest, he will never see the Ark, never mind if she was girl-child. Rav Kook, the first Chief Rabbi of Israel, attempts to eliminate this problem by understanding the flags that represented the tribe as also accurately representing each individual in the tribe. For Rav Kook, the desire to have the flags of angels, who have no will, becomes about the individual will.

The Jewish people desired flags like those the angels bore at Sinai. They wanted every individual to be able to choose an aspect of divine service that suited his personality, just as each angel executed a specific function, as defined by his flag.

To leap from tribal flag to individual desire requires Rav Kook to assume that every person born to the tribe will desire to serve God in the same manner as the tribe—the internal and the external flags will match. He has no need to ask what will happen if the flags do not match, because it could never happen.

My flag does not match my desire for divine service. It is through the lens of mismatched flags that I fervently and reverently seek to understand Jewish tradition and to make my home within it. I'll leave the flag waving to the angels.

5/24/2011 4:00:00 AM