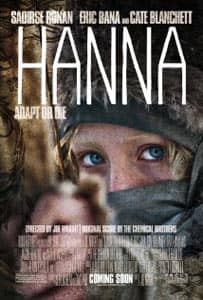

Hanna tells the story of a genetically modified girl (Saoirse Ronan) stolen away by her father (Eric Bana) to a snowy wilderness where he raises her in the way he thinks best—by reading to her out of a reference book and training her how to kill or be killed, all the while conspicuously denying her access to music. When she decides she is old enough, he allows her to push a red button that alerts a long-suffering CIA agent (Cate Blanchett) of her presence and begins a deadly game of cat and mouse that crosses two continents and results in the deaths of a whole lot of people—mostly at the hands of Hanna herself.

Hanna tells the story of a genetically modified girl (Saoirse Ronan) stolen away by her father (Eric Bana) to a snowy wilderness where he raises her in the way he thinks best—by reading to her out of a reference book and training her how to kill or be killed, all the while conspicuously denying her access to music. When she decides she is old enough, he allows her to push a red button that alerts a long-suffering CIA agent (Cate Blanchett) of her presence and begins a deadly game of cat and mouse that crosses two continents and results in the deaths of a whole lot of people—mostly at the hands of Hanna herself.

Hanna is as well crafted as its protagonist's genetic code, its action as brisk as her bow and arrow. The acting on all counts is convincing. Director Joe Wright certainly knows how to make an engaging movie. He excels particularly at integrating the world of the story with the film's sound effects and score. Wright has developed the ability to film sound. Scenes from his previous films come to mind: Liz (Keira Knightly) spinning on a swing in Pride and Prejudice as Jean-Yves Thibaudet's beautiful piano playing seems to make the season change around her; the click! click! click! of the typewriter keys as Brioni (Romola Garai) clops down the hospital hallway in her nurse's shoes as she is trying to atone for her misdeeds as a child by retelling the fateful tale of her sister and friend in Atonement; the haunting way in which Nathaniel Ayers' (Jamie Foxx) cello fills a Los Angeles overpass in The Soloist.

In Hanna, electronic musicians The Chemical Brothers provide the soundtrack, and Wright weaves their score into the world of the film. In one especially masterful scene, as Hanna crawls through the labyrinthine passageways of a CIA interrogation facility, the fluorescent lights pop on and off in time with the music, turning Hanna's escape into a sort of dance, highlighting the syncopated movement of this girl who has never heard music. Joe Wright knows how to do things with sound and image that are breathtaking. And yet . . .

I wish he had devoted his considerable talents to a different story.

Hanna is a very depressing tale of lost innocence. It begins with images of pristine, snow-capped hills and slumbering snow-white swans, and it ends in an abandoned, decrepit amusement park in the shadow of the fangs of a tunnel shaped like the open jaws of a wolf. In between, a 16-year-old girl does horrific things to countless people, often with nothing but her bare hands.

I have the same problem with this movie that I had with Kick-A**. That film—if you are so unfortunate as to remember it—concerns a down-and-out high school boy and a father and his 7-year-old daughter who dole out violent vigilante justice to a ring of local criminals. The flick is an unsettling combination of scenes of high school girls being groped, sex behind soda shops, and first-person-perspective killing sprees forced upon the audience without conscience or moral direction. Kick-A** is more filth than film.

Judged by its content, Hanna is not nearly as depraved. Judging by ethos, however, the films are close cousins. Both expect their audience to cheer the murderous actions of their protagonists. The audience is supposed to relish the slaughter of Hanna's enemies. This isn't too much to ask in itself. We cheer the destruction of evil in films all of the time. But there's something different about watching evil brutally dispensed at the hands of a little girl. And not just a little girl, but a little girl who has had all grace and compassion programmed out of her psyche.

Even this would be okay if the films themselves condemned the brutality. Were Hanna and Kick-A** satirical or even ironic, we could applaud them. Since they are not, we must not. These films expect us simply to enjoy the violence. (And more tragic still, because both of these films are so well made, that becomes a very easy thing to do.)

These films need a "Maximus moment." In Gladiator, Maximus, after vanquishing yet another arena of horrors, turns to the crowds (and the theater audience) and yells, "ARE YOU NOT ENTERTAINED!?" In that moment he begs our consciences to question the right-ness of enjoying such a terrible, bloody spectacle.

These films need that moment. Otherwise, we are simply a mob distracting ourselves in the dying days of whatever empire we are part of, gathered in a coliseum of our own construction and cheering the dramatized death and dismemberment of our own sons and daughters.

My little sister shares the name of Hanna's protagonist. It's a happy coincidence, because it pulled me out of the story long enough to notice what was going on in the film.

Hanna is a child. We owe children better than this.

5/4/2011 4:00:00 AM