I thought we were invincible ~ Last sentence, never punctuated, of my journal entry for September 11, 2001

As of this writing, Osama bin Laden has been dead for eight days. I found out while playing D&D at my friend Kenny's house; we wrapped up the game and sat in front of the television waiting for the president's press conference to start, even though we already knew what he would say, more or less. I remember letting out a long breath when Mr. Obama made it official. Often, we respond to the big events in life by saying how "unreal" they felt, but I didn't feel that way about this one. No, this story had weight.

There have already been plenty of analyses and opinions given about bin Laden's death—too many, to be honest. I don't want to add to that pile. People will debate about the material significance of the American operation in Pakistan until next November, I'm sure. Being neither an expert nor a pundit, I'll refrain from that discussion. But it would be a lie to say the story hasn't had an effect on me, and it would take a heart of ice to call it meaningless.

I was 15 years old in 2001, a sophomore at Metro High School in St. Louis. We were taking a quiz over Ancient Rome—the parts I liked, with Hadrian and Marcus Aurelius—when we heard about the first plane. We turned on the television to hear the news, and saw the second plane hit the towers. Mr. Trapp, whose love for the classics had undoubtedly led him to stoicism, shut the television off after that. "Nothing we can do about it," he said, and pointed at the quizzes.

We didn't do much else that day; mostly, we gathered in the cafeteria and watched CNN. I remember hearing someone in my year mutter, "Why should I care? It's not like I know anyone in New York," and wondering how someone could be so unmoved by such horror. I suppose I know better now, after Afghanistan, Iraq, New Orleans, and the rest; there's a threshold at which ignoring suffering is the only real defense against being consumed by heartache. Maybe my classmate just hit his threshold earlier.

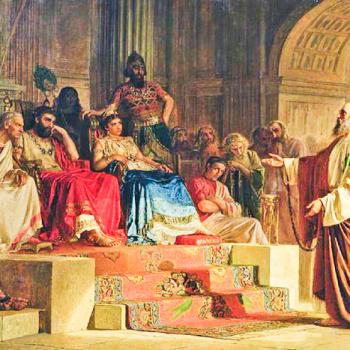

I have grown up in the age of the War on Terror—or, as the magazines called us within weeks of the event, Generation 9/11. It has been the backdrop to my adolescence, the basic topic of my political discourse. And it has always been clear that these events were never just about the protection of the United States from terrorism—that, regardless of our official positions and our hopes to the contrary, that the conflict would always, sometimes more overtly, sometimes less, be a religious war.

"We welcome people of all faiths in America," President Bush assured us, "and we're not going to let the war on terror or terrorists change our values." But of course, he said that in response to Jerry Falwell, who made statements like, "I think Muhammad was a terrorist." I remember passing by a restaurant in St. Louis a month or so after the attack and seeing a sign in the window: "We are not Muslims. We are Sikhs. We love America!" A statement not of solidarity or toleration, but of survival. We are not Muslims. You could hear the silent plea: Please don't hurt us.

It didn't matter whether our official desire was only to root out terrorism. The Crusader fervor clearly had its appeal, and too many Americans fell back on the notion of the country being a "Christian nation" in a search for a strong identity in the face of the attacks. And of course, that sentiment is still quite present today: one only needs to look at the controversy over the Park51 mosque last year, or at the statements of Brian Fischer that "Islam has no fundamental First Amendment claims," to see that, to many, we're in a war of Christianity versus Everybody Else.

And the simple fact is, when so much of your homeland is caught up in that mindset, it really sucks to be a 15-year-old kid who was raised among Everybody Else.

I was a Pagan teenager at a time when the world seemed to say we needed to pick a side in the Christian/Muslim dichotomy. Pick one: Christian civilization or Islamic chaos. It didn't matter that the vast majority of Muslims were people who had never done me harm, and it didn't matter that I had no particular love for Christianity as an institution; the "with us or against us" mindset existed. People asked us to make that false choice every day. They still do.

Here's the truth: at first glance, the Scott family appears decidedly uncosmopolitan. We have mostly been white Missouri Protestants since at least the Civil War. But two of my cousins have married Iraqi husbands and have children who attend Christian elementary schools during the week and classes at the mosque on the weekend. And of course, there are my parents, through whom the beautiful, messy web of Paganism extends. I am sure that if I were to shake the tree a little more, I'd find more unexpected faiths. I doubt we are that far out of the norm. The idea that the United States is a Christian nation, its only variations coming from different denominations, is a lie, and one that has to be fought.

Does the death of Osama bin Laden change anything? I don't know. It feels like it. But we can't forget that his madness can too easily lead to madness of our own. It is too easy to think that "Islam" is "the enemy"—or "Witchcraft," or "Christianity," or any other abstract ideology that excuses us from thinking of other people as people. We must strive against that temptation. It is far too easy, once we have given in one time, to give in again, and again.

5/15/2011 4:00:00 AM