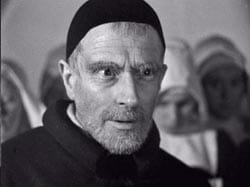

As last weekend's glorious yet surprisingly controversial beatification of Pope John Paul II reminds us, the debate over what constitutes true holiness (or perhaps more precisely, what we Catholics expect true holiness to look like) is far from settled. Given the context, this seems an ideal time to reflect on Monsieur Vincent, a classic French biopic of St. Vincent de Paul that highlights his undeniable sanctity while simultaneously challenging viewers to examine a number of damaging preconceptions they may have about what it means to be a saint.

As last weekend's glorious yet surprisingly controversial beatification of Pope John Paul II reminds us, the debate over what constitutes true holiness (or perhaps more precisely, what we Catholics expect true holiness to look like) is far from settled. Given the context, this seems an ideal time to reflect on Monsieur Vincent, a classic French biopic of St. Vincent de Paul that highlights his undeniable sanctity while simultaneously challenging viewers to examine a number of damaging preconceptions they may have about what it means to be a saint.

Faced with the daunting task of distilling a beloved hero's life into a few short hours, the film's writers omit de Paul's early days altogether, focusing instead on the events that produced the apostolate for which he is famous: his tireless efforts on behalf of the poor. While serving as pastor of the town of Clichy, Monsieur Vincent recognizes the dire circumstances confronting the destitute members of his flock but struggles with the most effective way to assist them. Realizing that his efforts on their behalf are nearly impossible without funds, he agrees to serve as chaplain for a prominent noblewoman and her family, on the condition that she grant him a generous stipend with which to support his charity. Yet this new-found wealth proves problematic as the fame and fortune that accompanies his lofty position becomes a stumbling block to the very people he most wishes to embrace.

Convinced that there is no value in half measures, he renounces his worldly possessions "so as to better love and serve the poor, my brothers and masters." Unfettered by wealth or fame, he is now free to walk among his ragged flock—an equal party to their suffering rather than a distant patron to be resented and distrusted.

Initially overwhelmed by the profound suffering he sees, Father de Paul is warned to "do like everyone else and not care, since only the rich can afford to care." But he refuses to succumb to the despair that plagues so many of his fellow mendicants, joining forces with a fellow clergyman in his daunting task of bringing food and hope to the poor that surround him on every side. Despite his best efforts to embrace them, the poor see him as a harsh taskmaster, stubbornly refusing to distribute food to those unwilling to better themselves and denouncing their laziness.

The wealthy noblewomen of the area, intrigued by the good priest's efforts, ask to participate in his work. Recognizing the vital role they (and their funds) can play in his future success, Monsieur Vincent welcomes their interest, but their shallow and selfish motives prove a source of endless frustration. Disgusted by their refusal to see his work as anything but an amusing hobby and overwhelmed by the seemingly impossible task before him, he is driven to the edge of despair. It is at this lowest moment that God sends him Marguerite Nasseau, a young milkmaid eager to assist him in his labors—and who is destined to become the first member of the Daughters of Charity.

The years pass—violent, tumultuous years that see Monsieur Vincent's efforts on behalf of his poor matched only by their ever-growing need. Gradually, his work attracts attention, admiration, and a mounting number of supporters. Yet even as the success of the institutions he has begun grows more assured, the future saint begins to doubt. Ever his harshest critic, he is plagued by fears that he has not done enough. "I slept too much," he laments. "I was a coward quite often. I gave in and closed my eyes so I could forget about misery." And so his story moves from a highly public struggle against poverty to a deeply private, yet equally intense spiritual one—one that is familiar to us all.

As one of only a half-dozen entries on the Vatican's "Great Films" list that deals directly with the life of a saint, the film's artistic merits alone would make it worthy of consideration. Pierre Fresnay's performance in the title role is unquestionably deserving of the praise it has received over the years, and the film's spare black-and-white cinematography is the perfect complement to the story's often traumatic images of poverty and suffering. Yet the film's spiritual insights are equally noteworthy, its message an implied refutation of the natural human tendency to mystify and dehumanize our heroes.

More Jerome than Thérèse, Monsieur Vincent's tireless exertions on behalf of his beloved poor are threatened by the sharpness of his tongue for those he sees as obstacles to his important work. When his faithful followers balk at the added burden of caring for Paris' orphaned infants, Monsieur Vincent lashes out, decrying their unwillingness to give above and beyond what they have already given. "I was a fool," he says harshly, "to believe I could move your souls; that I could lead you out of your repulsive solitude." And while it is this very feistiness and singleness of purpose that mark him as the perfect man for the job, his reaction is both unfair and uncharitable. It is, in fact, entirely human.