At the start of the 20th century, Italian immigrants were arriving at Ellis Island at the rate of 100,000 a year. Many stayed in New York City, settling in an area that came to be known as "Little Italy." Life was rough: large families were crowded into tenement apartments, men eked out a living on subsistence wages, and they faced prejudice from their neighbors. There were few places they could look for help.

At the start of the 20th century, Italian immigrants were arriving at Ellis Island at the rate of 100,000 a year. Many stayed in New York City, settling in an area that came to be known as "Little Italy." Life was rough: large families were crowded into tenement apartments, men eked out a living on subsistence wages, and they faced prejudice from their neighbors. There were few places they could look for help.

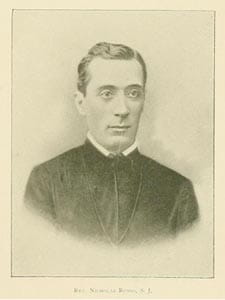

One of them was the Catholic Church. Michael A. Corrigan, the Archbishop of New York, made outreach a priority of his administration, founding Italian parishes throughout the metropolitan area for their benefit. He also assigned some of the best priests in the archdiocese to this work. After asking the New York Jesuits to start a new parish on the Lower East Side, Father Nicholas Russo (1845-1902) was picked to head it.

Born in Italy, Russo joined the Jesuits at 17 and studied in France and the United States. After his ordination, he was sent to Boston College as a philosophy professor. Over the next eleven years, he wrote two textbooks and served as acting president of the college. Between 1888 and 1890, he taught in New York and Washington before returning to a Manhattan parish, where he doubled as a speechwriter for Archbishop Corrigan.

Flexibility is a cornerstone of Jesuit life, the readiness to go anywhere and assume any task for what founder St. Ignatius Loyola called "God's greater glory." A respected professor and college president, Russo gave up a successful academic career to serve in the tenements. A biographer writes, "It must have been, humanly speaking, no small sacrifice . . . for he had held high positions in Boston and New York and his work had lain almost entirely among the better instructed and wealthy."

But Russo said he would gladly spend his life among his "poor Italians." He and his fellow Jesuit Aloysius Romano went right to work:

We rented an old bar-room, turned ourselves into carpenters, cleaners, and decorators, made an altar and two confessionals, cleaned the walls, painted the inside doors, etc. -- in a word gave the appearance of a chapel and put up a big sign on the outside, "Missione Italiana della Madonna di Loreto."

The chapel intentionally opened on August 16, 1891, the Feast of San Rocco. Getting the men to come to church was a challenge. The San Rocco Society participated, but, Russo commented, "I could not help looking with dread to the following Sunday."

Historian Mary Elizabeth Brown notes that Neapolitans, Sicilians, and Calabrians were living in what had once been an Irish neighborhood. They were mainly Catholic, but their fellow Catholics didn't always welcome them. The local pastor offered them the church basement for worship, but later reneged. One old-timer, Bernard Lynch, wrote an article for a Catholic journal about what he considered the "Italian problem."

In an 1896 article for The Woodstock Letters, an in-house Jesuit magazine, Russo called Manhattan as a "favorite place" for Italian immigrants. Their hope was to "find work here more easily, and thus better their condition." He estimated their local numbers at fifteen thousand. "Nearly all the southern provinces of Italy," he added, "are represented with their different dialects, customs, and manners." Most only understood their own dialect: "They understand good Italian fairly but cannot speak it."

There were numerous challenges, not all financial. There was local prejudice from nearby pastors. Russo was once denied use of the upper church at Old St. Patrick's Cathedral,* he wrote, "for reasons which a priest should feel ashamed to give." He occupied a small room in a tenement house. All in all, it was lonely, hard work, and he couldn't help believing that

. . . things would not be in so bad a shape now . . . if they had been taken in hand in due time . . . Look back to the first years of Italian immigration. Who was there to smoothe [sic] their first difficulties, to warn them of the danger, to sympathize with their distressed condition, to turn their mind to heaven, and to remind them of their immortal soul?

But the people's "own indifference" was a problem, too. And sometimes there was outright hostility, as Russo later recalled:

We were oftentimes received with the coldest indifference; not seldom avoided; at times greeted with insulting remarks. The word pretaccio (pretender), as we passed by, was one of the mildest.

Still, he felt sympathy for the men, who "work like slaves." Eventually, he added, "We had a nice little crowd" in the parish. His compassionate approach helped win over the people: