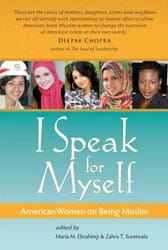

In a time when many wonder if American Muslims can be American and Muslim at the same time, a new book seeks to defy the labels and show the diversity and unique mesh of what it means to be American, Muslim, and female. In I Speak for Myself, forty women have come together to share their stories about being a Muslim in America, discovering their religious identities, and breaking down myths and stereotypes.

In a time when many wonder if American Muslims can be American and Muslim at the same time, a new book seeks to defy the labels and show the diversity and unique mesh of what it means to be American, Muslim, and female. In I Speak for Myself, forty women have come together to share their stories about being a Muslim in America, discovering their religious identities, and breaking down myths and stereotypes.

Patheos' Dilshad D. Ali spoke with three contributors to the book—Zahra T. Suratwala (co-editor), Mona Rajab, and Samaa R. Abdurraqib—about owning their own stories, the dangers of judging how "Muslim" someone is, and how America is the best place for a Muslim to live.

Why is there a need for Muslim women to tell our own stories?

ZS: It is essential for [Muslim women] to own our stories. There's a lot of misconceptions about hijab, confusions about oppression as a cultural thing versus religion. For many Muslim women, the comment is, "Stop telling me what you think I'm about, and let me tell you what I'm about." And the important thing to note is that there are forty of us in the book, but there are millions of us around the world. When I say I am speaking for myself, that's what I'm doing. My story does not represent exactly that of the Muslim women next to me.

SA: The stories are both individual and they have resonance with lots of different communities. There's something very specific and individual that makes each story important. I think it's important to present Islam like it's not the antithesis of what is American. Americans can't even conceptualize an American Muslim woman. Does she even exist? That's why these are stories are so important.

From all the rich experiences in your lives, how did you choose what one thing to write about?

SA: When I got the call for the submission, I had just written an article about being black and Muslim, and that was what I was constantly thinking about. I wrote a draft, but it didn't work because it didn't explain what it was like for me growing up. So I started to think back to the most influential time growing up as a Muslim, and I thought back to college, back to my religiosity, and how that made me who I am today. What Islam meant to me before that college, and a particular moment in college became the catalyst to who I am today.

MR: [This book] was my only outlet for me to share what happened to me. (Editor's note: Rajab's story discusses the problems she faced from family members over her decision to wear a hijab or headscarf.) It was such a pervasive experience. I just let it all out. Even growing up, Islam was a casual thing. I never got into Islam until the past 10-12 years. And I got such an overwhelming negative response for wearing the hijab. I felt it was a story I had to share—how important it was for me to wear the hijab and how my closest family wasn't supportive of my decision.

ZS: It was important for me to have an essay in the book focusing on the small things in life—that sometimes being a Muslim woman in America doesn't mean a pivotal thing happens. Sometimes it's just your life that moves forward. As I thought of myself on the spectrum of religiosity, finding my identity and my place in my family, none of it was really a struggle. Things just fell into place around me. Sometimes it is a struggle, and sometimes it is not. This is the American Muslim experience.

Samaa R. Abdurraqib's essay says, "Muslims vacillate between levels of religiosity, and that doesn't mean they're any more or less Muslim." How aware are Muslims and non-Muslims of this?

SA: It's a very important point, and a lot of essays in the book say this as well. Not all Muslims practice the same. People who have preconceived notions of Islam can't conceive that Muslims are different from each other. The same things happen within Muslim communities: You don't wear a hijab, you're perceived to be less Muslim. Not true.

ZS: In Islam, there are things that outwardly show how religious you are, which may not be the case in other faiths like Christianity. When it's time for prayers, you're praying or you are not. You wear a hijab or you have a beard or you don't. There are outward signs that people can point to. It's like people say, "They're doing it, check. Or, they're not doing it, uncheck." But no one ever knows the whole story about how a person practices his or her faith.