This past weekend, scholars gathered at the 57th annual convention of the College Theology Society (CTS), a professional organization of college and university professors of theology, most of whom are Catholic (full disclosure: I am a former Board member and editor of the 2008 annual volume). The theme, "They Shall Be Called Children of God: Violence, Transformation, and the Sacred," sought to reflect on a number of questions: are religions the cause of violence? Does the Bible promote violence? How has the Church sought to heal the effects of violence? Did Jesus' willing death implicitly condone violence? Do our relationships sometimes manifest violence? Do our social or political stands sometimes encourage violence? These and many other questions evince contemporary theologians' concerns about how our language about God might offer ways of confronting, challenging, and healing the reality of violence in these times of rapid cultural change.

This past weekend, scholars gathered at the 57th annual convention of the College Theology Society (CTS), a professional organization of college and university professors of theology, most of whom are Catholic (full disclosure: I am a former Board member and editor of the 2008 annual volume). The theme, "They Shall Be Called Children of God: Violence, Transformation, and the Sacred," sought to reflect on a number of questions: are religions the cause of violence? Does the Bible promote violence? How has the Church sought to heal the effects of violence? Did Jesus' willing death implicitly condone violence? Do our relationships sometimes manifest violence? Do our social or political stands sometimes encourage violence? These and many other questions evince contemporary theologians' concerns about how our language about God might offer ways of confronting, challenging, and healing the reality of violence in these times of rapid cultural change.

A key question that I find myself wrestling with in the wake of the conference is about Christian participation in violence today. It is a matter of historical record that there have been violent chapters in Christian history: the Crusades and the Inquisition come to mind, and it is important to acknowledge, as Pope John Paul II did, that the Church today must repent of its past participation in violence. What is more difficult to address, though, is the question of whether the Church continues to participate in violence.

Let me be clear: I am not talking about whether any Christian is guilty of violence. I am a member of a Church among whose leaders are those who have abused children and covered it up. Almost every day I read about the extent of our crisis, in part because I want to pray for the wounded and recommit myself to the shared task of repentance, healing, and renewal. I am therefore not blind to the reality that people of faith are, like people everywhere, guilty of sin, sometimes violent sin.

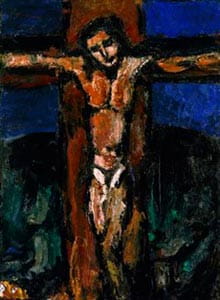

Yet I am asking a rather more systematic question. Sins of child abuse and cover-up are "hidden violence" in the sense that they are clearly grotesque departures of individuals from the teachings of Jesus. Hidden violence has become especially insidious in light of the fact that our bishops did not stop it. I want to ask, though, about "public violence" that comes from doing the very work that Jesus calls the Church to do—prayer, evangelization, and mission in the world. Some violence erupts from failing to be Christian; but is there violence that erupts precisely from being Christian, from practicing one's faith and living out the implications of one's faith?

Again, the historic answer is clearly that violence has sometimes erupted from living out one's faith. The pogroms against Jews are obvious examples, related to the explicit condemnation of the Jewish people in passion plays and other reflections on the death of Jesus in literature and drama. Some chapters of our missionary history in Africa and South America have been violent. More recently, thankfully, there have been efforts to encourage dialogue between Jews and Christians, as in the famous Passion Play of Obergammerau, and missionary work has developed a greater understanding of inculturation and authentic intercultural conversation.

But what of the contemporary question: is the Church sometimes violent today? Even if we recognize that the days are gone when clerics could burn people at the stake or the pope could launch an army, we may still ask whether in our Christian life we contribute to violent rhetoric, or participate in structures in society that do violence to people.

My thesis is that the Church at its best today does cause pain, but does not do violence. It is the pain of the surgeon excising a tumor, or setting a bone, or cauterizing a wound. It is the pain of a mother sending her daughter to rehab, or a father wrestling the car keys from his drunken son's hands. It is the pain of women doing an intervention with their addicted friend, the pain of a man confronting his adulterous friend with the truth of how he is hurting his wife. It is the pain of Jesus telling his disciples "I have come to bring not peace but the sword" (Mt. 10:34), mindful that truth unmasks evil and causes the implicated to lash out with anger.