A couple of weeks ago, my family and I were rocked by something that happened just a few miles up the road from where we live: a teenage boy killed a teenage former girlfriend. Chances are good that part of the story has to do with the lacerations of love.

A couple of weeks ago, my family and I were rocked by something that happened just a few miles up the road from where we live: a teenage boy killed a teenage former girlfriend. Chances are good that part of the story has to do with the lacerations of love.

Societies ancient and new have wrestled with questions of how to steer people into relationships that benefit themselves, their families, and the common good. Sex is never a private issue, for it touches on the ways that people perceive and behave toward each other. In fact, what this and other stories remind us of is that there is potential danger when sexual questions are not public questions, when people believe that intimacy has no implications for families and for societies as a whole.

Sexual issues must be brought into the light of day, for only strong social pressures can restrain the runaway passion that gives birth to the twins of eros and anger. Conservatives rightly point out that we are foolish to sweep away, through short-sighted legislation, social mores that have developed over centuries. Yet progressives are right to point out that social mores always reflect a society's winners, most of whom have not (for example) been stay-at-home moms or, for that matter, single people. The right balance is what the best of Christian tradition (not exclusively, of course) has practiced: rootedness in a textual tradition, but informed by contemporary commentary. It is no surprise that in matters of sex, that balance of commentary on a textual tradition was struck by Jesus time and again.

Our century-plus of modernity is not the first to grapple with sex. Ancient cultures could see the implications of getting sex wrong, and for that reason wrote the theme into the very DNA of its literature. It is no surprise that ancient myths abound with the coupling of gods: Isis-Osiris; Zeus-Hera; Anu and his consorts. Sex touches some of the great mysteries of human life: birth, puberty, marriage, jealousy, even killing. Reading the Bible as a collection of ancient literature, one can see the way that a text like Genesis shares some similarities with other ancient texts (like Gilgamesh and the Enuma Elish). Among other things, it offers a way of situating a culture, not unlike nomads planting a stake in the ground and saying "this is where we now live."

To say what God intended "in the beginning," as the opening words of Genesis say (that is, the newer Priestly creation story) is to say something about what leaders in fifth-century Israel recognized as central to their identity as a nation: the social roles of men and women. When they wrote "God created man in his image; in the divine image he created him; male and female he created them" (Gen. 1:27), they were not blind to the difficulty of creating clear definitions between men and women—definitions which some today find problematic. Ancient writers were familiar with the phenomena of gender-bending (e.g. "A woman shall not wear an article proper to a man, nor shall a man put on a woman's dress; for anyone who does such things is an abomination to the LORD, your God" Dt. 22:5). Yet they chose to highlight and extol certain roles that had evolved from their prehistory: primarily household roles for women; primarily military, agricultural, and political roles for men. Specific gender roles aside, what is significant is the theological claim: God created us both, and wants us to get along. And we're going to have to do it as a whole society, not as isolated individuals.

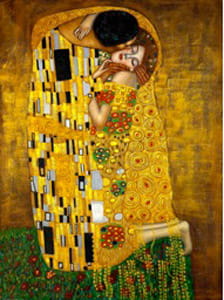

The word "sex," ambiguous as it is in English, comes probably from the Latin verb secare, to cut. It's an image of the human situation, too often cleaved by the otherness that men perceive in women and vice versa. The Priestly writers and editors, to whom Jesus makes reference in his most specific commentary on marriage ("Have you not read that from the beginning the Creator 'made them male and female'," Matt. 19:4) understood this common belief, and wished to suggest a way forward. Editing Genesis by putting their newer creation story first, they then went on to paste an older, Yahwistic account: