In early January, after Gabrielle Giffords, a member of the U.S. House of Representatives, was shot in the head outside a Tucson, Arizona supermarket, I soon wondered how I would address the matter with my kids. Not my own (I have none), but the approximately 100 sophomores who were entrusted to me for a year-long course in scripture.

In early January, after Gabrielle Giffords, a member of the U.S. House of Representatives, was shot in the head outside a Tucson, Arizona supermarket, I soon wondered how I would address the matter with my kids. Not my own (I have none), but the approximately 100 sophomores who were entrusted to me for a year-long course in scripture.

The shooting had to be discussed, but how?

A few days later, President Barack Obama gave me an opening. In his remarks at the memorial service, the President quoted Psalm 46:

There is a river whose streams make glad the city of God,

the holy place where the Most High dwells.

God is within her, she will not fall;

God will help her at break of day.

A few days later, in my classroom, I shut off the lights and flipped on the overhead projector. I pulled up Psalm 46, and together the class and I read through it. We also read a portion of the psalm the President did not quote: "God is our refuge and our strength, an ever-present help in distress. Thus we do not fear, though earth be shaken and mountains quake to the depths of the sea, though its waters rage and foam and totter at the surging."

For all four scripture classes that day I repeated the same thing. We read the psalm, and afterward I let the students sit with the words in silence, without the lights. I wanted to create a solemn space, an atmosphere more like a chapel than a classroom.

After a few minutes of silence, the room still dark, I began to ask for thoughts, offering a number of questions that might, I hoped, open a conversation, questions like: "What do you think about the psalm? Is God your refuge and your strength? If bad things happen, in what way can the psalm be true? How do you respond to evil and suffering?"

At first, they were speechless, motionless. Then one hand, followed by another—the conversation I hoped for began.

My students spoke about trials in their lives—an aunt dead from cancer, a brother killed in a car accident, a family torn by divorce—and shared candid reactions to the psalm's hard-to-reconcile claims. Some spoke about a testing of faith and the good that could emerge from evil, while another (one of my best students) said, "I think it sounds cliché. It's just what people tell themselves when they are hurting." This led me to ask, "Can the cliché sometimes be true?" which, in turn, led to a back-and-forth on the value of prayer and the existence of God.

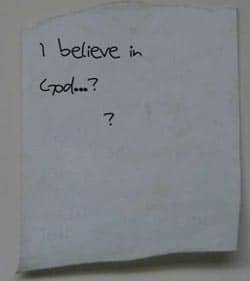

Those classes, and that day, were sacred moments. There had been an uncovering. In the darkened room, in the mild glow of a projector screen bearing ancient words, I had been given an x-ray of my students' spiritual life. The images were good and bad, mysterious and clear. Above all, they revealed that though only 15 and 16 years old, my students had a complex inner world with questions and anxieties that too often languish unaddressed.

They also caused me to rethink how Catholics, especially those in Catholic schools, nourish and assess Catholic identity. Many students who confessed confusion about good and evil or doubts about God's existence were capable of acing a religion exam and participating in the rituals of the faith. They could list the Sacraments and explicate John 6, or happily read at Mass and serve as a Eucharistic Minister. They could, in other words, say and do things that suggested a strong Catholic identity.

But beneath those well-intentioned actions, those same students were (and are) frequently confused by, or in denial of, foundational truths—chief among them the existence of God. To be sure, their confusion or denial generally does not arise because students are stubborn or hard-hearted; rather, it arises because their schools, their families, or their faith communities simply haven't devoted enough time to exploring the big questions.

For me, this poses questions: Does Catholic education spend enough time on those foundational matters, particularly in the junior high and high school years? Do curriculums at all levels, including in parish catechetical programs, need to be modified to better meet students where they are at, which is often at the first line of the Creed? Put more concretely, does it make sense to spend an entire year on scripture if that year could be better spent working through the main arguments for the existence of God and handling objections to the same?

As those questions are taken up, we must remain cautious about how we assess the Catholic identity of both an institution and a person, especially in today's climate where so much conspires against belief. A student may graduate from a Catholic high school without a desire to attend Mass or with doubts about the divinity of Jesus; however, that student might have started high school an atheist or an agnostic, and might have come to believe in the existence of God. At the high school level, in the circumstances of the modern world, that is a triumph. There need to be more like it.

7/21/2011 4:00:00 AM