Editor's Note: The following is an edited transcript of a podcast in the Veritas Riff series. For more information on the series, and for other installments, go to veritasriff.org.

The Veritas Riff is a group of friends who combine deep faith with world-class expertise in subjects ranging from politics, science, culture, business, medicine, and more. They offer their informal take on the big questions facing us all. I'm the host of the Veritas Riff, Curtis Chang.

The Veritas Riff is a group of friends who combine deep faith with world-class expertise in subjects ranging from politics, science, culture, business, medicine, and more. They offer their informal take on the big questions facing us all. I'm the host of the Veritas Riff, Curtis Chang.

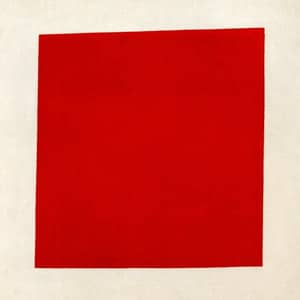

Recently I wandered into the modern art wing of my city's museum, and found myself looking at a large canvas with a single red square. That's all there was: a single red square. I realized that here is an object that a major cultural institution in my city has deemed worthy of my attention—and I just don't get it.

I'm not the only one who often has a hard time comprehending modern art. In fact, it seems that Christians especially feel this disconnect. Today we're asking the question: Why is modern art so hard to 'get'? For an answer, we're talking to Daniel Siedell, who has taught modern art history at the University of Nebraska.

When and with whom did modern art begin?

The founding modern artists were people like Gustave Courbet, Claude Monet, and Edouard Manet, artists who are associated with impressionism and realism, and others like Paul Gauguin and Paul Cezanne later in the 19th century. They looked at painting not as an act of recording what the artist saw, but as a means of exploration, of representing emotions, of making art do something more than they had experienced in the past. They even sought to make art function in a religious register.

Did the original wave of modern artists have religious impulses? Were they Christian?

They were not Christian. By the 19th century, most French intellectuals and artists were not practicing Christians. They were shaped by the church, and some were more favorably oriented toward it than others. Courbet was a very strict atheist—but Gauguin was fascinated with religious belief. He was fascinated by those ordinary French peasants who had a sincere, pious faith. In fact, Gauguin tried to make painting that operated in that way.

Ambivalence toward religion seems to characterize modernism in its various expressions, whether music, literature, or art. Modern artists thought they had thrown off the shackles of Christianity, but discovered they still needed something like faith to provide the sense of transcendence that art requires.

I agree. One of the more important aspects of the history of modern art, and what I teach my students, is that the history of modern art is inflected by religion and shaped by theological concerns, even if the artists were not explicitly aware of it. The artists wanted to make art that functioned in a sacred, personal-transformative context. Deprived of the authority of the Church, they made art their religion.

This is what makes modern art very interesting. Artists who don't have an orthodox Christian bone in their bodies are making paintings that they're intending, even in subconscious ways, to function in this very specific, sacred, and you could say a secular-Christian, environment.

When I visited the modern art wing recently, it struck me that there was far more silence and contemplation there than I've found at any church service recently. Most churches have the background noise of church music, and a large screen up on the stage that's constantly shifting visuals. Do you think Christians struggle to 'get' modern art because we struggle with silence? Is there an irony that just as modern art struggles to appreciate Christianity because it's lost its theological roots, so now Christians struggle to appreciate modern art because we've lost our contemplative roots?

We're bombarded with so much imagery that appears to us immediately. So when we go to a museum or we go to a gallery, we see a painting and it enters our vision immediately and we're trained to make a quick or snap judgment on that work as an image. Most of those art works are meant to be absorbed and experienced over time.

Where would the most famous and commercially successful Christian artist out there, Thomas Kinkade, fit on your map of how art ought to work?