Story Summary

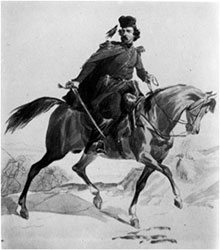

Practicing its own brand of gunboat diplomacy, France occupied Algiers in 1830 with a force of 30,000 soldiers. Greeted at first as liberators by Arabs unhappy with decadent Turkish rule, the ignorance, arrogance, and broken promises by the French occupiers soon alienated the population. Two years later, tribes in the province of Oran elected Abd el-Kader's aged and reluctant marabout father, Muhi al-Din, to lead a jihad against the intruders. His first act was to abdicate in favor of his twenty-four year old son.

By 1832, Abd el-Kader's bravery in battle, intellectual mettle and religious piety had demonstrated that he was prepared for the role his father unexpectedly cast upon him. As a youth, Abd el-Kader excelled at everything he did. Muhi al-Din believed his son was a prodigy with a divine destiny that required a thorough grounding in Islamic law, as well in mathematics, philosophy, rhetoric and medicine. Horsemanship and hunting were essential for building character, especially courage and patience. To expose Abd el-Kader to the world's diversity and complexity, Muhi al-Din took him on a two-year pilgrimage, stopping in Alexandria, Cairo, Mecca, Damascus and Baghdad. Abd el-Kader's first loves were prayer and study, yet he was also prepared for military combat.

|

| Battle of Machta, 1835 |

A resilient and divinely inspired Abd el-Kader won the begrudging respect of his French adversaries and the admiration of English onlookers during his fifteen-year struggle. His best weapons were his diplomatic astuteness, his desert hardened horses and his Jewish intelligence network that kept him aware of political attitudes in France toward its poorly conceived African adventure.

Faced with French determination and scorched earth tactics against tribes supporting him, Abd el-Kader decided further resistance would cause only futile suffering. In December 1847, he negotiated a truce with veteran General Lamoricière. The terms: the general's written word, confirmed by the governor general of Algeria (King Louis-Philippe's son), agreeing to send him into Middle Eastern exile in return for his promise to never return to Algeria.

|

| General Lamoricière |

The Second Republic, born two months after Abd el-Kader's surrender, disowned the agreement of the monarchy. The new government tried to save face by bribing him to release France from its word. Unmoved by offers of luxury living in France, he insisted on holding France to the word of its generals. Twenty-five members of the emir's entourage died in clammy royal prisons from disease and despair—victims of French politics in which popular opinion distrusted the emir's word, and weak governments lacked the courage to honor its predecessors' commitments. In 1852, Abd el-Kader was liberated thanks to an admiring President Louis Napoleon and a lobby of Catholic clerics, intellectuals, military officers and former prisoners whom the emir had treated with unexpected humanity. Abd el-Kader was sent to Bursa in Turkey on a generous French pension where he lived for two years; then to Damascus where he was enthusiastically received by the Arabs and joined the mixed Jewish, Christian, and Muslim intellectual stratum of the city.

On July the ninth, 1860, his life of prayer, study and teaching was shattered. Angered by rebellious Christian minorities who refused to pay their taxes, Turkish authorities instigated reprisals that turned into a virtual pogrom. The emir converted his huge home into a sanctuary for the European diplomatic community whose embassies were the first targets of the violence. He and a band of Algerians plunged into the nearby Christian neighborhood and brought thousands to the safety of his residence. Two days later, an angry mob at his door demanded he turn over the Christians. Abd el-Kader refused, saying it was against the teachings of Islam to kill innocents. The crowd melted away in the face of his determination to defend those under his protection.

After the riots, Abd el-Kader was credited with saving 10,000 lives, including those of the American, British, French and Russian consuls. Hailed throughout Europe, Russia and America as a great humanitarian, he received the French Legion of Honor, gifts from Pope Leo IX, President Lincoln, Queen Victoria, and other heads of state. His most valued accolade, however, was a letter from Chechen Emir Shamil, who praised him for his courage to do what his faith required—to protect the innocent.

During the last twenty years of his life, the emir became a spiritual bridge between the European and Muslim worlds, epitomized by the role he played garnering Arab support for the Suez Canal project and his participation in the Masonic movement. Defying the skeptics, Abd el-Kader remained true to his word and never returned to Algeria. Upon his death in 1883, the New York Times hailed him as " one of the few great men of the century."

Visit the Patheos Book Club for more resources on Commander of the Faithful.