Blythe, California is about halfway between Los Angeles and Phoenix, a short drive west of the California-Arizona border, in the middle of endless, unscenic brown. It's one of those towns that people mock, a place as bland as its name, remembered for gas stations and fast-food restaurants, a place where travelers are grateful not to call home.

Blythe, California is about halfway between Los Angeles and Phoenix, a short drive west of the California-Arizona border, in the middle of endless, unscenic brown. It's one of those towns that people mock, a place as bland as its name, remembered for gas stations and fast-food restaurants, a place where travelers are grateful not to call home.

A few weeks ago, my colleagues and I gathered on a big bus to caravan from Palm Desert, about two hours further west down the I-10, to this ridiculed desert outpost. More specifically, to one of its only attractions: the Ironwood State Prison.

The visit was part of our faculty orientation, a time usually spent in reflection on the big ideas and the pressing issues that will shape the new school year. In the prayerful, meditative setting shaped by themes of Catholic education and Jesuit spirituality, orientation days always arrive like a downpour on famished land, giving nourishment long after. But they are also, most of the time, sedentary. Usually, we stay put.

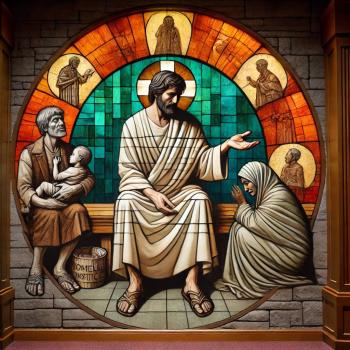

This year, however, our leadership had something different in mind. How, they asked, can we more fully experience Christ? Throughout the summer, as planning commenced, Jesus' words in Matthew 25 became the guiding theme:

For I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me drink, a stranger and you welcomed me, naked and you clothed me, ill and you cared for me, in prison and you visited me.

After months of discernment and weeks of planning, it became possible: we were going to visit prisoners.

On a mid-August day, at about 10am, we pulled up to the facility. After ID checks and the scrutiny of a metal detector, we were led past layers of razor-tipped fence that looked like one gigantic and brutal cage. We then made our way through another barred and bolted portal where IDs were checked one more time.

After walking through those vault-like bars, my group turned toward the prisoners. They were on "yard"—running around the track, working out, laughing, huddling. Whey they saw us walking toward them, they stared. We stared back, and kept walking.

Our destination was the prison education area, a place that, to the extent possible, serves as a school.

There, we spoke with inmates at all levels of education. Some were working to get their GED or, through a local college, their bachelor's degree; others simply wanted to know how to write and read. We spoke to them in the textbook room, and I saw piles of math and history books stacked on tables. I had flashbacks to my college bookstore. Strangely, the room felt safe and familiar.

About seven or eight inmates spoke. They were friendly, intelligent and, most dramatically of all, normal. While I didn't expect them to be monsters, I did expect something hinting at aggression, something to indicate that they were, at root, other. I expected bitterness or anger, or resentment. But they spoke with all the ease and eloquence of a neighbor at the supermarket. They weren't scary or menacing. They were . . . like us.

And they wanted to learn. One inmate, probably around twenty, talked about his history classes, about how much he loved learning about other cultures beyond his immediate environment. Another had earned two bachelor's degrees and was hoping to obtain his M.B.A. Our hosts displayed an enthusiasm for learning rarely seen, even in prestigious schools.

A short time later, we moved into small groups to hear more details about prison life and to talk about faith. The inmate paired with my group said that while he would never claim that prison was a good thing, it had, he said, allowed God to break through. Prior to prison, he had no relationship with God; but with all the time to read and think and pray, something within him, he said, began to open up. He committed a crime, he said, and there was no denying it. But in acknowledging his sin and in turning toward the inspired words of scripture, a spiritual freedom began to blossom. Astonishingly, unbelievably, he spoke thankfully about an existence that, from the outside, appeared replete with misery.

In the weeks following our visit, I've been searching to understand what I saw and heard. To borrow from Nigerian author Chimimanda Adichie, I had succumbed to the "danger of the single story." Based on my own limited and fortunate life, I had come to believe that prisoners were basically different from those outside, deviant in some essential way. Four hours on prison grounds suggested otherwise.