Now Featured at the Patheos Book Club:

Now Featured at the Patheos Book Club:

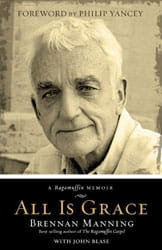

All Is Grace: A Ragamuffin Memoir

By Brennan Manning

Book Excerpt: Chapter One

You don't always get what you ask for. I expect most children have heard that line in one way or another. It's a difficult lesson to learn, yet it's one that is essential to growing up. But when I heard my mother, Amy Manning, say that, I knew she wasn't talking about something petty like a ball glove or a doll. She was speaking about something much deeper.

My mother had prayed for a girl. What she got on April 27, 1934, was a boy, me, Richard Manning. My name has not always been Brennan.

It was the Great Depression in Brooklyn. My brother, Robert, had been born just fifteen months earlier. Over the years, I've seen many mothers grin and talk about a second child born so quickly on the heels of the first as "my little surprise." But not my mother, not back then. To her, I was one more disappointment, one more unanswered prayer.

My mother was born in Montreal, Canada. At the age of three, both of her parents died within six days of each other in a flu epidemic that swept the city, killing thousands. Those were days when the bedtime prayer "If I should die before I wake" actually had teeth. There was no one to take her in, so my mother was sent to an orphanage. Her stay lasted ten years. God only knows what happened to her in that time. I've wondered if anyone was there to help a three-year-old grieve? Did anyone remember to celebrate her birthday? Did they even know her birthday? What about Christmas—were there gifts for her? Who were the adult females behind those walls and what kinds of mothering impressions, if any, did they make on her? And what about the men? Was my mother abused? Raped? All of this and more are probabilities for that bruised decade of my mother's life. But my questions have no answers because what happened there stayed there. Then again, maybe she would have answered my questions in the same way she answered so many others: You don't always get what you ask for.

When she was thirteen, my mother was adopted by a man known as Black George McDonald. Why he adopted her, or any of the details surrounding the adoption, I do not know; I do know that his name sounds like it came straight out of a novel. I've been told that he had made some discoveries of gold and was involved with building the town of Alexandria, between Montreal and Toronto. So Black George evidently had financial means, but I don't know his intentions. He must have had some kindness, however, because my mother wanted to become a nurse and he funded her nursing education. His gift led her to Brooklyn, where she completed her nurse's training, met and married my father, birthed my brother, prayed for a girl, and got me. Although you can clearly deduce that knowing of my mother's disappointment over my birth is painful for me, I have nonetheless committed to try to express gratitude in these pages. So in that spirit, I say, "Thank you, Black George McDonald. I'm not quite sure what all I'm thanking you for, but your grace toward my mother led to my birth, wanted or not. So thanks."

The nurse's training my mother received was based on the popular methods of the 1920s. The word parenting, if you can believe it, did not become commonplace until the late 1950s; prior to that

it was childrearing. The rule was discipline, regimentation, sternness, and a minimum of affection. Early behaviorists like J. B. Watson influenced the thought and approach. Here's a quote that speaks

volumes as to the mood of the times: "Mother love is a dangerous instrument that can wreck a child's future chance for happiness." Watson advocated a brisk handshake every morning between parent

and child, nothing more. As alien as that sounds now, that was the world into which my brother and I were born. In many ways it was also the world in which my mother grew up.

As I try to understand the mysteries of my life, I must consider the voices and experiences that shaped my mother. Her odyssey from orphan to registered nurse to young mother was nothing less than heroic survival, but heroes don't always make the best parents.

Add to this story a man named Emmett Manning, my father. He and my mother were, in many ways, a pair of contrasts. Unlike my mother, he was not orphaned as a child. In fact, from the time

my parents were married, my father's parents lived with us. My mother's father figure was some shadowy benefactor, Black George, but my father's father was a very real alcoholic. I have no idea what my mother lived through as a girl, but I saw glimpses of the rages my father endured as a boy. I learned then that there is more than one way to orphan a child.