If asked whether I am finally letting God love me, just as I am, I would answer, "No, but I'm trying." ~ Brennan Manning, All is Grace

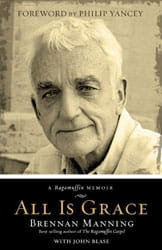

What a disappointment we are to ourselves. How fearful we are, particularly those of us in ministry, to let our true selves be seen. How rare it is to experience acceptance—by our family, our friends, our lovers, ourselves, even God. These are the thoughts, the feelings really, that accompanied me as I read speaker and author Brennan Manning's memoir All Is Grace.

What a disappointment we are to ourselves. How fearful we are, particularly those of us in ministry, to let our true selves be seen. How rare it is to experience acceptance—by our family, our friends, our lovers, ourselves, even God. These are the thoughts, the feelings really, that accompanied me as I read speaker and author Brennan Manning's memoir All Is Grace.

Written in what he calls the "winter" of his life as a homebound 77-year-old man, the book is a sparse series of sketches, the lasting memories that haunt a man who is beginning to slip into the next world. These images, like Brennan himself, often feel like a gallery from Picasso's blue period—hurting, lonely, pale figures full of unresolved pain and unmet longing. And yet, just as blue represents the divine in iconography, there is something deeply beautiful and even holy about Brennan's struggle to carry the heavy cross of self-hatred, searching for some kind of embrace, some final release into God's compassionate love.

All Is Grace is the story of an itinerant, a self-described "ragamuffin," who craves friendship from peers, from God, and maybe most desperately from himself. While serving as a Little Brother of Jesus in the Zaragoza desert of Spain, a spiritual mentor tells Brennan that he is a man "poor in spirit" and that this particular poverty makes him available to receive the "greatest grace." For all of his success as an author, an acclaimed speaker, retreat leader, and spiritual guide, Brennan's memoir is the tale of a man struggling with spiritual poverty, desperately working to receive grace.

An abusive mother, an alcoholic father, a friendless childhood, a life-long addiction to alcohol—all help to hollow out Brennan's soul with a gaping yearning to be loved, to be liked, to be known and accepted. This primal ache drives him into the military, the Catholic priesthood, communities of prayer and poverty, marriage, and life as a celebrated speaker and author, yet none of these settings answers the deep ache to be known. It's only what Brennan calls the "vulgar" grace of God that from time to time relieves him of his endless hunger for approval.

The book is sparse and at times dark. This seems to have caused great discomfort and anxiety for the publishers who felt compelled to stuff the opening and ending pages with testimonies from friends and appreciative Christian celebrities, asserting Brennan's gift as a spiritual leader. I'm not sure why the publishers felt it necessary to collect and print these letters. Was it to extend the book's page count? Was it to counter Brennan's confessions of sin? For me, these testimonials read like a kind of cover-up that only detracts from the central message of the book, which Brennan states as, "God loves you unconditionally, as you are and not as you should be, because nobody is as they should be."

The first time I heard Brennan preach was in the living room of my parent's house, as a college student in the late 1980s. My father, a friend of Brennan's, had suffered a scandalous divorce and remarriage, and was being reinstated (after six years) as pastor of our little community church. Brennan, a defrocked priest, knew what it was like to be shamed, and that night he preached like an early Apostle—fierce and articulate and full of vulnerability. I can still hear his voice in my ear thundering throughout our house, "Abba, I belong to you. Abba, I belong to you. Abba, I belong to you."

The last time I saw Brennan was at my father's funeral in 2003. The service was held in a high school gym with the podium at the center of the floor surrounded by folding chairs that fanned out toward the bleachers. Behind the speaking platform were three tall, rough-hewn crosses that our church often used on Easter Sunday. The funeral was held at night and the room was dark except for a few dim lights and a table full of candles. Just before the service began I heard a popular Christian speaker say derisively to another colleague, "Brennan came in last night. He was stumbling around the parking lot drunk." "Is he here?" the other inquired. "Doubt it. He's probably passed out in his room."

The service began and there came my time to go the podium and offer my remembrances. As I approached the microphone I noticed a solitary figure in the darkened shadows, just behind the cross to my left, the one, according to tradition, that held the body of the repentant thief. I remember the figure was bent over, hands shaking, clothes rumpled and disheveled, face unshaven, eyes heavy and swollen with sorrow. At first I assumed a homeless man had walked in from the street, but then I noticed the thick white hair and I knew it was Brennan. I have not seen Brennan since that moment. He slipped out before the service ended, but I will never forget his wasted, distraught, grieving body sitting behind the thief's cross. It was an image of spiritual poverty, an image that matched my own grief and emptiness.