Anti-Catholicism was essentially a staple of life in the state of Connecticut, where freedom of religion was only officially legislated in 1818. In newspapers of the time, Catholics were told: "Until the light of Protestantism shone in the world there was no religious freedom. Popery, with its iron heel, treads out the life of religious liberty as fast as it is born." America was a Protestant nation, and the central image they invoked was that of the Mayflower.

Anti-Catholicism was essentially a staple of life in the state of Connecticut, where freedom of religion was only officially legislated in 1818. In newspapers of the time, Catholics were told: "Until the light of Protestantism shone in the world there was no religious freedom. Popery, with its iron heel, treads out the life of religious liberty as fast as it is born." America was a Protestant nation, and the central image they invoked was that of the Mayflower.

But in early 1882, in a New Haven church basement, a group of Catholic young men led by their parish priest invoked an older image, that of the explorer Christopher Columbus. It wasn't a Protestant who discovered America, they argued; it was a Catholic. Catholics, therefore, were "entitled to all rights and privileges due to such a discovery by one of our faith." To reflect their Catholic and American heritage, they called themselves the Knights of Columbus.

At a time when health benefits as such didn't exist, K of C members could rely on an income during sickness and provision for their families upon death. The Knights offered men an opportunity to socialize in a Catholic atmosphere, but more than that, they would promote the life of the Church both locally and nationally, and if needed, come to her defense in the public arena. From these humble beginnings, the Knights have expanded worldwide to become the Church's largest fraternal organization.

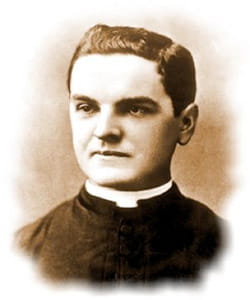

But who was the man that founded the Knights? Who was this man who is on his way to becoming a saint? He was born in Connecticut on August 12, 1852, the oldest of thirteen children, the son of Irish immigrants from County Cavan, who found work in Waterbury's factories. For a while, young Michael McGivney worked in a local spoon factory. An intelligent and sensitive boy, from early on he was interested in the priesthood, and he began seminary studies at sixteen.

At Baltimore's St. Mary's Seminary (America's first Catholic seminary), McGivney—a good student with natural leadership skills—made a strong impression on his peers and superiors. Upon ordination in December of 1877, he returned to Connecticut, where he spent the rest of his life as a parish priest. Two of his brothers later joined him in the priesthood.

At St. Mary's Church in New Haven, the young priest made a strong impression. Small and slight of build, he was, historian Christopher Kauffman writes, "an unassuming, pious priest who easily elicited the trust of the laity." Parishioners remembered his "earnestness of manner," his "strength of purpose" and his "indomitable will." He was also possessed of a beautiful speaking voice. A local Protestant man who was blind attended St. Mary's every Sunday just to hear "that voice."

Since the end of the Civil War, Connecticut's Catholic population had grown significantly. It was a predominantly working-class immigrant body working under dangerous conditions. At any time, families might suddenly find themselves homeless and penniless. To meet this concern, fraternal societies provided sickness and life insurance. But many such groups had an anti-Catholic bent, and Catholic workers had to look elsewhere for support.

Father McGivney at St. Mary's Church in New Haven set out to meet this need. He aimed to help workers and their families, provide an authentically Catholic gathering place for Catholic men, and to defend and strengthen the Church. In the words of McGivney's biographers Douglas Brinkley and Julie Fenster, the Knights of Columbus were to be "benevolent, fraternal, and soundly religious."

Nearly anyone could afford the coverage it provided. Members got a sickness benefit of five dollars a week. A death level payout of fifteen hundred dollars was given to widows, the equivalent of four years' earnings. The first members had names like Driscoll, Geary, Healy, McMahon, Mullen, and O'Connor. These Irish-Americans chose to name their group for the Genoa-born explorer. "Christopher Columbus" was at once a name thoroughly American and thoroughly Catholic.

The Knights weren't the only Catholic fraternal organization, but they soon became the largest and most significant. From St. Mary's basement, they spread rapidly throughout the state of Connecticut. While overseeing the growth of the Knights, Father McGivney continued as a hard-working parish priest. On August 14, 1890, he died of pneumonia contracted from illness and overwork. By then, there were six thousand Knights. Within a few years, they would be an international organization.