It might be American literature's very first spoof on the Holy Ghost. A large cockatoo, originally trained to assist in a striptease, deserts its post onstage and dives straight for a large hoop earring worn by a man in the audience, one Ignatius Reilly. Fearing for his ear, Ignatius flees the bar, dashes into the street, and is nearly mashed by an oncoming bus. The ensuing commotion ties up three or four subplots and hurls the main one toward its satisfying conclusion.

It might be American literature's very first spoof on the Holy Ghost. A large cockatoo, originally trained to assist in a striptease, deserts its post onstage and dives straight for a large hoop earring worn by a man in the audience, one Ignatius Reilly. Fearing for his ear, Ignatius flees the bar, dashes into the street, and is nearly mashed by an oncoming bus. The ensuing commotion ties up three or four subplots and hurls the main one toward its satisfying conclusion.

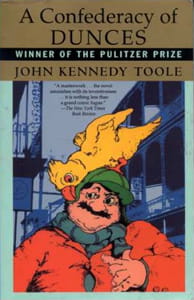

The scene is from Confederacy of Dunces, published in 1980, more than ten years after the death of its author, John Kennedy Toole. If the bird bit sounds like a Deus ex Machina, it is. If, moreover, it seems a bold appropriation from Flaubert's "A Simple Heart," where the Holy Ghost appears as a pet parrot, that's every reader's call to make. For me, it works just fine because it keeps faith with the book's generally cartoonish tone. The cartoonishness works in its turn because, though Toole wrote in the early 1960s, he managed to anticipate some of the cartoonish qualities of the 21st-century Catholic experience.

Ignatius, Confederacy's antihero, is a figure few readers would care to identify with. Obese, a sloppy eater, and a fashion nightmare—the earring, though exceptional for him, does little harm to the effect of his usual getups—he's also a hypochondriac obsessed with his pyloric valve. Though well into adulthood, he lives with his widowed mother, in the very house he was born in. His one trip outside New Orleans—to Baton Rouge, by bus—touches off a crippling attack of panic and nausea that has kept him housebound ever since.

But what makes Ignatius such a prophetic figure (and his creator, by extension, a prophet) is the rich virtual life he manages to lead. In his own mind and in his own words, Ignatius is a very formidable figure. He has worked out his own thought system—a kind of medievalism based on the philosophy of Boethius—which he expresses with considerable force and eloquence in a collection of Big Chief writing tablets. He engages with the general culture, feeding himself a steady diet of Annette Funicello-Frankie Avalon-type movies, which tend to support his thesis of a decaying society. Through long, often spiteful letters, he carries on what amounts to a long distance relationship with Myrna Minkoff, a New Yorker he met while studying at Tulane.

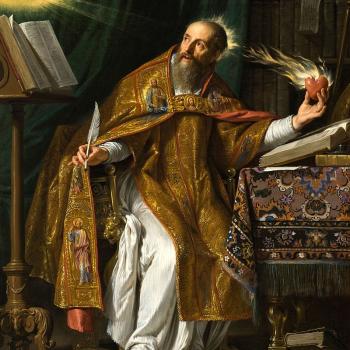

No longer a regular churchgoer and inclined to mock his mother's rosary beads as "religious hexerei," Ignatius remains in some ways more Catholic than the pope. He criticizes St. Peter's current successor—presumably John XXIII—as insufficiently authoritarian, and is quick to invoke the saints against his enemies. As he writes to one of his former professors:

Your total ignorance of that which you profess to teach merits the death penalty. I doubt whether you would know that St. Cassian of Imola was stabbed to death by his students with their styli. His death, a martyr's honorable one, made him a patron saint of teachers.

Pray to him, you deluded fool, you "Anyone for tennis?" golf-playing, cocktail-quaffing, pseudo-pedant, for you do indeed need a heavenly patron. Although your days are numbered, you will not die as a martyr—for you further no holy cause—but as the total ass which you really are.

Ignatius signs off—pseudonymously, as on the internet—as "Zorro."

If Ignatius Reilly is even more an everyman—and an EveryCatholic—now than he was back in the days of Camelot, it's because whatever defined those times defines ours even more. Social change and political polarization? Check. The isolating effects of urban life? Check. Dissatisfaction with Church leadership, and indeed, with authority in general? Please.

That increasing numbers of Catholics, like Ignatius, contradict themselves and contain multitudes—of opinions and inclinations—is now a matter of record. A 2008 Pew Research Center survey reveals that, though 57 percent of Catholics report that religion is "very important" in their lives, only 41 percent attend Mass on a weekly basis. Or maybe the greater contradictions and multitudes are contained by the Church herself. It's well known that Catholics support same-sex marriage at a higher rate than the general population. Yet the decision by the Bishops' Conference to re-issue the conscience-friendly 2007 Guide to Faithful Citizenship, dashed the hopes of pro-life activists, some of whom had called for a "Catholic Tea Party" to pressure the bishops into taking a harder line against pro-choice candidates.