Years ago, as a visiting student reading theology at Oxford University, I underwent something of a conversion process with regard to liturgy. I'd been brought up as an average American boy in the Chicago area with more or less decent experiences of the mass, but not until I drank deep of the history and aesthetics of Catholic liturgy did I have the sense that my youth faith practices had been—to use Robert Barron's catchy description, "beige." By that word, he refers to the colorless, flavorless rituals that fail to challenge, characteristic of a church that has accepted a more-or-less status quo.

Years ago, as a visiting student reading theology at Oxford University, I underwent something of a conversion process with regard to liturgy. I'd been brought up as an average American boy in the Chicago area with more or less decent experiences of the mass, but not until I drank deep of the history and aesthetics of Catholic liturgy did I have the sense that my youth faith practices had been—to use Robert Barron's catchy description, "beige." By that word, he refers to the colorless, flavorless rituals that fail to challenge, characteristic of a church that has accepted a more-or-less status quo.

For me, it was an immersion in a world that had a much longer and deeper grasp of history that proved thought-provoking. Several memories come to mind: going to St. Mary's Church, where the (then-Anglican) Blessed John Henry Newman used to give the University sermons, till his conversion to Catholicism in the wake of the Oxford Movement banished him from Oxford for the rest of his life; listening to the New College Choir singing Fauré's Requiem, a beautiful setting of the mass; attending mass (in Latin) at St. Aloysius Gonzaga Church (where Newman's Oratorians reside); going to meetings at the Catholic Chaplaincy and the Newman Society; praying the Liturgy of the Hours on retreat with the monks of Worth Abbey; traveling around Europe to see the great cathedrals of Chartres, Cologne, and many others; celebrating midnight mass on Christmas eve at St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican; undertaking for the first and very formative time the Spiritual Exercises of Saint Ignatius Loyola at Campion Hall, home of the Oxford Jesuits.

What I learned is that liturgy connects us to a history of people reflecting on the meaning of Jesus' life and work. It challenges us to see the world as the place where God's kingdom is unfolding right now, but which summons us from our slumber to help make it happen. It draws us to the deep truths of ourselves as individuals before God and as a community of people practicing faith together, even when it's hard. It slices open our hearts and lays bare the searing demands of love. It reminds us of our better selves by showing us a mirror in which we are both plaintiff and defendant charged with sin, but set free by a Christ who goes to the gallows in our place.

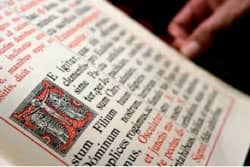

The new translation of the mass in English is a welcome change that reminds me of that conversion experience. Knowing Latin makes the changes feel familiar and (in a word) right. To use one example: I remember when, at Saint Aloysius, I first recited the response before communion: Domine, non sum dignus, ut intres sub tectum meum: sed tantum dic verbo, et sanabitur anima mea. (Lord, I am not worthy, that you come under my roof: but only say the word and my soul shall be healed.) I was perplexed by this text, having been used to the usual English version: "Lord I am not worthy to receive you, but only say the world and I shall be healed." I learned that the Latin text was a reference to the story of the Centurion who asked Jesus to come heal his servant, but whose faith was such that he believed Jesus could do it simply by giving the word (Matthew 8:5-8). The experience of encountering the Latin text provoked in me a curiosity about the origins of the liturgy, leading to a greater appreciation of its reflection of the gospel. By contrast, the beige American version was a little flat. The depth and beauty of the liturgy, coupled with the art, history, and theology that gave rise to the Church's worldview like the foundation stones of its cathedrals, instilled in me a sense of awe and reverence, but also a sense of connection to Jesus and to Catholics around the world, praying with the same language.