In the new book, Left, Right and Christ: Evangelical Faith in Politics, co-authors and Evangelical Christians Lisa Sharon Harper and D.C. Innes tackle some of the hottest political issues of our day from two very different ends of the Evangelical continuum. In this interview, the authors defend their differences on key issues, as well as share what the process of writing this book together was like, and what their ultimate hopes are for this project.

In the new book, Left, Right and Christ: Evangelical Faith in Politics, co-authors and Evangelical Christians Lisa Sharon Harper and D.C. Innes tackle some of the hottest political issues of our day from two very different ends of the Evangelical continuum. In this interview, the authors defend their differences on key issues, as well as share what the process of writing this book together was like, and what their ultimate hopes are for this project.

(Visit the Patheos Book Club for more conversation on Left, Right and Christ.)

How can two people who share the same faith come to such different conclusions about political issues?

Lisa Sharon Harper: The chapter on our personal journeys says it all!

- We both see the scripture as authoritative.

- We both love Jesus.

- We both believe in the transformational power of the Cross.

- We both believe our faith must be lived out in our world.

Yet, our experiences of this world have shaped what we see in scripture. For example—David shared with me that before writing this book he wasn't aware that the Bible talked about poverty so much. Well, there are more than 2000 scriptures about poverty in scripture. How is it possible to miss them and not realize they are there? Michael Emerson and Christian Smith explained in their groundbreaking book, Divided by Faith. Their research revealed that White and Black evangelicals see the world (and scripture) differently because of their experiences of our world. Both groups have two significant similarities and one major difference:

Similarities:

- Because of our evangelical faith, black and white evangelicals both see the world through the lens of rugged individualism; a marker of our Evangelical faith. Evangelicals believe each individual has the power to choose heaven or choose hell through their acceptance or rejection of Jesus Christ as Lord.

- Because of our evangelical faith, black and white evangelicals see the world through the lens of relationalism. We believe salvation is about more than beliefs, principles, or precepts. Salvation is about relationship, our reconciliation with God, with each other, and with the rest of creation all through the power of Jesus' death and resurrection.

Difference:

- According to Emerson and Smith (both of whom are white evangelicals), white evangelicals tend to see the world through the lens of anti-structuralism. This is the case because of their experience of the world, which tends to have far less personal encounter with systems and structures. Meanwhile, Black evangelicals, who have personally experienced the power of just and unjust systems to impact whole people groups, see the world through the lens of structuralism.

This explains why David and I can see such different things in scripture and in our world; the scripture we actually see has been fundamentally influenced by our life experiences of this world. For David, Jesus is the triumphalist provider of money, power, and personal peace for all who accept him. For me, Jesus is savior, redeemer of all things—every relationship created in the beginning: humanity's relationship with God, humans' relationships with each other, with the rest of creation, with self, and with the systems that govern us for all who follow him. To me, Jesus is the one who frees individuals and whole people groups from political oppression, economic exploitation, and the brokenness of sin.

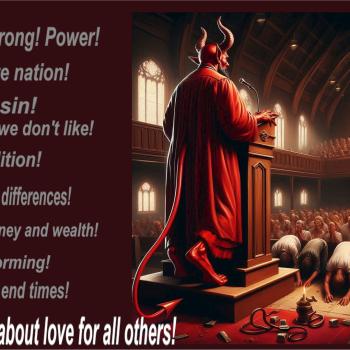

Thus, if Jesus is one's triumphalist provider of money, power, and salvation from personal sin, then one would naturally gravitate toward political platforms with triumphalist narratives, promotion of economic inequity through the deification of an unregulated market, and the brunt of one's moral concern would rest on issues caused by individual sin (ie. abortion and same-sex marriage).

But, if Jesus is the savior and redeemer of all relationships, including humanity's relationship with the systems that govern us, then one can see Jesus, who is God, was there with Moses and Jeremiah and Nehemiah and Isaiah. And Jesus' social location, a marginalized Nazarene in an occupied, poor, and oppressed land, gives new meaning to Luke 4, Matthew 5-7, Luke 10, 11, and 18, Mark 6, and Matthew 25. With this lens, one sees Jesus' confrontations with the powers and one understands his call to live according to God's kind of dominion—the dominion of love; not according to the dominion of men, which oppresses, exploits, and celebrates inequity.

D.C. Innes: I approach Scripture in a traditional, Evangelical manner. I look at the passages in their literary, cultural, historico-grammatical, and biblical-theological contexts. I approach them humbly and prayerfully, always ready to have my view of things radically altered. I read them not as an isolated interpreter, but with the church. I don't know how much of this if anything Lisa does with rigor, but she has said on several occasions that she reads the Scriptures through her experience. For that reason, she begins her public addresses with autobiography and family history. We established this difference at our book launch. So whereas I subject my experience to the judgment of Scripture, Lisa approaches Scripture through the lens of her personal experience and the experience of her ancestors. This is a huge hermeneutical difference. If it characterizes the difference between Evangelical left and right, then it invites us to ask whether we are using the term "Evangelical" equivocally. Given how radically different our conclusions are, the alternative, it seems to me, is to question the perspicacity and authority of Scripture. And that is unacceptable.