The new film "The Mighty Macs" tells the story of a women's basketball team at a small Catholic college in Pennsylvania (now Immaculata University). The school is one of many established by the Sisters, Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary (I.H.M.). Their foundress is a fascinating person who deserves her own movie. Theresa Maxis Duchemin holds a unique place in American Catholic history. She played key roles in the founding of two religious communities, one for white women and the other for Black women, and she headed both of them.

The new film "The Mighty Macs" tells the story of a women's basketball team at a small Catholic college in Pennsylvania (now Immaculata University). The school is one of many established by the Sisters, Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary (I.H.M.). Their foundress is a fascinating person who deserves her own movie. Theresa Maxis Duchemin holds a unique place in American Catholic history. She played key roles in the founding of two religious communities, one for white women and the other for Black women, and she headed both of them.

She was born in 1810 as Almeide Maxis Duchemin, in Baltimore, to a Haitian mother and a white father who never acknowledged her. Arthur Howard was a British officer visiting American relatives when he began a brief affair with Theresa's mother. The child never met him, but she recalled having him pointed out to her at a distance. She also recalled feeling no desire whatsoever to meet him.

But she did grow up in a loving family, her mother being a servant to the Duchemins. An elderly French couple who fled the Haitian Revolution, they doted on her. She grew up a strong-willed child, surrounded by love and used to having her way. She took the name Duchemin as her own in honor of the childless couple who looked on her as a grandchild.

Her mother, a "Free Woman of Color" (to use the language of the day) worked as a nurse. In 1829, at age nineteen, Almeide joined the Oblate Sisters of Providence, the nation's first religious community for Black women. Taking the religious name Theresa, she was the community's only American-born member, the rest being Haitian and Cuban. In time her own mother joined.

The Oblates didn't have an easy time of it. Many white Catholics doubted they would ever make "good nuns." In 1831, as a cholera epidemic struck Baltimore, they nursed the sick, and Theresa's mother was among those who died in the process. Later the City Fathers publicly thanked the white sisters for their service, while ignoring the Oblates altogether. In time, Theresa assumed leadership of the Oblates.

During the 1840's, however, the community experienced a major crisis as ecclesiastical authorities tried to disband it. Facing the possibility of forcibly losing her religious vocation, Theresa decided to make a new life for herself up North. Being seven-eighths white (she had blond hair and blue eyes), she decided to no longer identify with her African-American heritage, and left the Oblates.

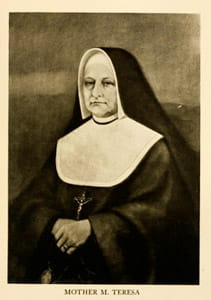

In Monroe, Michigan, she started working with a young Belgian priest named Louis Florent Gillet, whom she had met several times in Baltimore. Father Gillet was looking for teaching Sisters. On November 8, 1845, the two founded the Sisters, Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary. For the second time she assumed leadership of a religious community, this time a white one.

Over the next decade, the Sisters opened several schools and orphanages throughout Michigan, with the strong support of the local Bishop, Peter Paul Lefevre. When she expanded her apostolate to Pennsylvania without his permission, however, Lefevre turned on her viciously. Knowing her family history, he described her to another bishop as having "all the softness, slyness and low cunning of the mulatto."

Lefevre used his authority as a bishop to depose Theresa as leader of the Michigan community she had helped found. She then planned to live with her community in Pennsylvania, but the local bishop took Lefevre's side and banned her from there too. Suddenly, after living her entire adult life as a religious, she found herself a nun without a community. She never gave up the hope, though, that one day she would return to the I.H.M.'s.

For nearly twenty years, she found refuge in Canada, where she lived with a community called the Grey Nuns of the Sacred Heart. Their superior, Mother Elizabeth Bruyere, sympathized with her and gave her a home. But Theresa always considered herself an I.H.M., continuing the wear the habit she had designed. And she continually wrote letters back to America requesting readmission to her community. Many times she came close to despair, but she never gave up hope.

In 1885, when Theresa was seventy-five, a new bishop lifted the ban, and she was allowed to live with the community in Pennsylvania. For the last seven years of her life, she held a revered status as foundress. As one historian aptly notes, few founders of a religious community have followed "so tortuous a path." In his 1990 history of Black Catholics, Father Cyprian Davis writes:

The story of African American Catholicism is the story of a people who obstinately clung to a faith that gave them sustenance, even when it did not always make them welcome. Like many others, blacks had to fight for their faith; but their fight was often with members of their own household.

Father Davis's words couldn't be more true of anyone than they are of Theresa Maxis Duchemin, a woman whose entire life was in some ways a struggle with racism both inside and outside the Church she loved at great cost.

11/15/2011 5:00:00 AM