Should we go by the cover of a book? We are warned not to. But in these days where large, corporate publishing houses spend huge amounts on getting the right mix of colors, shapes, pictures, fonts, and of course, the titles and expect to sell millions of copies, make the writers famous, and the publishing company a handsome profit, we have become inured to the gloss and the tinsel. And whatever the formula such publishing houses have fine-tuned to sell these books we know that it does not always work and therefore the business of "book liquidators" in whose vast warehouses we can buy books priced $30 for a buck. But I am straying.

Should we go by the cover of a book? We are warned not to. But in these days where large, corporate publishing houses spend huge amounts on getting the right mix of colors, shapes, pictures, fonts, and of course, the titles and expect to sell millions of copies, make the writers famous, and the publishing company a handsome profit, we have become inured to the gloss and the tinsel. And whatever the formula such publishing houses have fine-tuned to sell these books we know that it does not always work and therefore the business of "book liquidators" in whose vast warehouses we can buy books priced $30 for a buck. But I am straying.

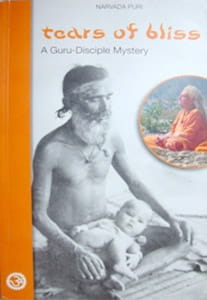

Recently, I received a book in the mail whose cover has so mesmerized me that I keep looking at it. My mind is stilled, and my eyes are glued to the visage of a yogi, sitting in meditation, with a little baby on his lap. The baby, naked, with eyes open, seems to be looking toward the camera, and it is as sweet-faced and angelic a baby as only babies can be. The picture is in black and white. Off to the side, in a box, is the picture of what seems to be an elderly woman, white, with grey hair, clad in saffron, meditating. The title of the book, in saffron, lower case, says tears of bliss, with the sub-title, A Guru-Disciple Mystery in simple black. I got this book shipped from India, after Patrick Levy, author of Sadhus: Going beyond the Dreadlocks, recommended it to me. I have spent the last week reading and re-reading this book, and stopping by my book-laden desk at home to take another peek at the cover. Who is this yogi sitting in meditation? Whose baby is it that lies beatific on his lap? Who is the woman on the cover? And what does the title of the book indicate/imply? This is a book about a modern day Lord Shiva being entranced by a Goddess Parvati, and about their life together.

The book, published in 2009, is by Narvada Puri, a disciple of Baba Santosh Puri of the Sri Panch Dasnam Juna Akhara, and the story is of Narvada Puri, a young German woman who went to India in 1969 desperately seeking to quell the spiritual tumult in her heart. There she met Baba Santosh Puri, the teacher, the sadhu belonging to the Panch Dashnam Juna Akhara (one of the ten organizations of Hindu renunciates that Adi Shankara, the 8th-century philosopher/sage helped organize), and the father of her three children. It is a story beautifully told, in broad brushstrokes—a book in free verse. It is also a story told in Narvada ji's voice, with traces of her German accent, but given structure and life by a loving editor, Darcy Cunningham.

The broad outline of the story of Narvada ji and Baba Santosh Puri is this: a young German woman, 24 years old, arrives in India in 1969 with "a sleeping bag, a shawl, a flute, and a copy of the 'I Ching'." For a year she travels the country experiencing the good, the bad, and the confusing that most "hippies" did as they came in search of love and seeking escape from war, aggression, material wealth, and spiritual dead-ends. Many simply got hooked on to the hookahs and chillums, free and copious sex, and smelly, languid laziness. Others, after their fill of "maya" and the Indian mess left the quest and headed home to the comfortable and predictable life of the Western grihastha or householder. But a rare few, whose spiritual hunger was deep, stayed, searched, and despite diarrhea and despair continued to look for that guru, that teacher who would guide them to the land of ego-less freedom. Narvada ji was one such.

After that initial year of tears and desperate searching she found Baba Santosh Puri living on a small island in the Ganga near Haridwar. And there she stayed despite every kind of challenge because she knew she had found her refuge and her teacher. Not knowing Hindi she could not speak with the Baba, and not knowing Sanskrit she could not understand the mantras, the chanting, and the prayers. She spent her first year on the island chanting nothing but "Om Namah Shivaya." Her quest for spiritual solace was such that she cried her eyes out almost daily, spent time serving her guru, who both recognized her as a disciple and a companion from previous lives, accepted her, and yet tested her, and tried to shoo her away as he saw the powerful forces of life that might envelop them in the tentacles of duties and obligations. For ten years she struggled, fed, and served the holy white cows in the ashram, and survived near death experiences.