Editor's Note: This is the first in a series of essays that examines the real world of Mormon missionaries and the real Elder Price. Read the author's Introduction.

The Book of Mormon Musical opens with a scene of Jesus, Mormon, and Moroni on Hill Cumorah in upstate New York. It is a brief and campy depiction of a Mormon theophany, something which appears absurd and laughable to many: the idea that gods and angels would be personally involved in burying gold scriptures. In many ways, it plays on a central Mormon tenet—not just the belief in the prophetic calling of Joseph Smith as translator and restorer, but the belief in continuing revelation. Such revelation not only makes seers of farm boys, but suggests that Jesus Christ and other Heavenly beings are present even in the most unlikely places, and that every human being can be spiritually enlarged beyond any border which mortal paradigms impose.

The Book of Mormon Musical opens with a scene of Jesus, Mormon, and Moroni on Hill Cumorah in upstate New York. It is a brief and campy depiction of a Mormon theophany, something which appears absurd and laughable to many: the idea that gods and angels would be personally involved in burying gold scriptures. In many ways, it plays on a central Mormon tenet—not just the belief in the prophetic calling of Joseph Smith as translator and restorer, but the belief in continuing revelation. Such revelation not only makes seers of farm boys, but suggests that Jesus Christ and other Heavenly beings are present even in the most unlikely places, and that every human being can be spiritually enlarged beyond any border which mortal paradigms impose.

Mormonism itself demands a generous imagination. We Mormons are urged to imagine one another's potential with limitless generosity, daring to believe that the most lowly, uncomely, unrefined person is potentially as glorious as any divine being represented with ultra-watt lighting on a Broadway stage. The Mormon imagination is telescopic, inviting us to see far into the distance, beyond time; to look into the Heavens and imagine that—even in the presence of such mind-boggling creativity as the stars and planets manifest—we humans and our incomprehensible future are God's "work and glory" (Moses 1:39).

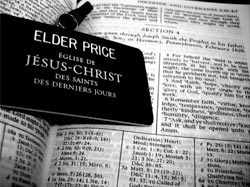

|

| Elder Price's name badge |

So, these divine beings in upstate New York do make a central statement about Mormonism and imagination. If viewed cynically, the suggestion that anyone might actually believe that gods and angels would behave so unexpectedly (or behave at all) appears simply naïve. Taken representationally, the scene implies (accurately) that we Mormons are accustomed to dealing with the unexpected, that we allow ourselves to be surprised by grace in many ways and places, that we don't "just believe," as one of the show's songs states, but that as we grow in love, we behave as love itself does. And love (says Paul) "bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things" (1 Cor. 13:7-8). It's not so much a habit of "making stuff up again" (as another show song claims) as it is a willingness to nurture glorious "what if's." Love persuades us to view ourselves and our brothers and sisters—comprising everyone—in the light of eternal prospects, granting the potential for individual and communal progress. This progress doesn't end. We Mormons don't believe in an either/or (Heaven or Hell) judgment immediately after death. We believe that as God's children, we may continue to learn and grow even after our earthly lives end. The only thing that prevents growth is a personal option for stasis.

That there are naïve Latter-day Saints is beyond question. That there are Mormons who don't understand the hierarchy of gospel principles, and assume that a belief in Kolob is equally important to faith in Jesus Christ, is true. But globalizing and reducing all Mormons to the stereotype of smiley, gullible replicas of each other is using imagination as a flat iron rather than a telescope.

The protagonist of The Book of Mormon Musical, Elder Price, doesn't appear until this Hill Cumorah tableau fades, and then, he's already a missionary.

The real Elder Price, as presented in this series of essays (Elder Brandon Price), agreed to imagine himself and others with a divinely generous imagination when he was ordained to the Melchizedek priesthood. In that moment, he was told that he now held "the keys to all the spiritual blessings of the church" and that he could "have the heavens opened . . . and enjoy the communion and presence of God the Father, and Jesus" (Doctrine and Covenants 107:18-19). His temple endowment magnified his godly imagination. He entered the temple in his Sunday clothes, and carried a bag that would change his life. In the bag were new temple garments. For the rest of his days on earth, he will wear this "Mormon underwear" as a constant reminder of his consecration. The depiction of garments in The Book of Mormon Musical predictably gets a small laugh—and you can almost hear the audience members whisper, "Oh of course! Magic undies!"—but we Mormons take our garments seriously. As much as a yarmulke or a priest's collar indicates personal commitment in other religions, garments, for us Mormons, serve as symbols of our promises to God.