Editor's Note: This is the first in a series of essays that examines the real world of Mormon missionaries and the real Elder Price. Read the author's Introduction.

The song "You and Me, but Mostly Me" from The Book of Mormon Musical, could have been written for a Mormon film or road show. Every returned missionary could tell a story about hard companionships. The "mostly me" attitude is often the issue. What's remarkable is how young men or women from different areas, and sometimes from different countries, learn not only to get along but to become brothers or sisters.

The song "You and Me, but Mostly Me" from The Book of Mormon Musical, could have been written for a Mormon film or road show. Every returned missionary could tell a story about hard companionships. The "mostly me" attitude is often the issue. What's remarkable is how young men or women from different areas, and sometimes from different countries, learn not only to get along but to become brothers or sisters.

The learning curve is often grueling, and requires maturity beyond what we would expect of 20-year-olds. The differences between the musical's Elder Price (a bright-eyed, most-likely-to-succeed type) and Elder Cunningham (a fantasy/sci-fi nerd) are quite common, as exemplified by one missionary's description of his companionship in the DR-Kinshasa mission:

My companion: Sports sports sports sports sports!

Me: Okay.

Me: Star Trek, Star Wars, Doctor Who, various Babylon!

My companion: Yeah, whatever.

|

| Elder Chirwa singing with Elder Alex Healey |

In The Book of Mormon Musical, all of the missionaries are white. In most African missions, however, Anglo missionaries work with Africans, and many will have at least one African companion. Some cultural conflicts are inevitable.

Elder Henry Lisowski, from Canada, found himself in a difficult companionship with an African missionary from a country where aggressiveness was the norm, and argument seemed braided into tradition. As the companionship continued, their quarrels went deeper and lasted longer. Elder Lisowski's initial instinct to repair the friendship devolved quickly into a determination to "show him he's wrong!" Finally, the two were yelling at each other while tracting. This is Elder Lisowski's description:

My companion started saying how all us white missionaries were failures, did things wrong, didn't baptize, and how the African missionaries were real missionaries. He just kept attacking and attacking, and I just kept defending until I was so angry that I wanted to attack back. And this thought started in my head: "African missionaries are bad because . . . etc., etc."

|

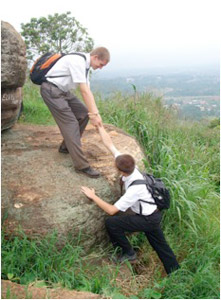

| Elder Lisowski and Elder Hunter, one helping the other |

As I considered what I was about to say, my mind froze. I realized, with instant clarity, that something had gone HORRIBLY WRONG. I was starting to think like a racist. It terrified me. I went silent. We got to the next rendezvous, and I told my companion to teach it because I COULDNT. My mind couldn't focus. I was absorbed in thinking of everything that I did which led to this, and what I could do to FIX it. The rest of the day was a struggle . . . and constant prayer filled it. Halfway through our last lesson, all that poor, weak effort I had put forth for patience and love paid off. My prayers were answered, and everything just clicked. And all my frustration was gone, and I loved him again. We talked a little after, and resolved it, and things are okay now.

Such self-awareness and humility are rare in one so young—and were rare in Henry Lisowski's pre-mission life. The mandate to serve in the name of Christ leads us to hard epiphanies.

Another African/Anglo companionship, between Elder Daniel Kesler (Utah) and Elder Aime Mbuyi (Congo), shows how service and honest conversation can fill the gap of a cultural divide.

Elder Mbuyi reported on how he and Elder Kesler learned to bridge their differences:

|

| Elder Henry Lisowski with Africans (dancing at a well dedication |