Reading theology, doing theology, and living a theology are—at one level—three very different activities. They are related, of course. And everyone, lay and ordained, reads, does, and lives a theology whether they are aware of it or not.

It's what I've described elsewhere as triage theology. That intuitive tagging of ideas about God as we move through life with the labels "dead and unworkable," "bruised and battered, but reliable and useful," or "needs more attention."

Reading theology can inform the way that you do theology and it may shape a theology that you can live. But, at one level, it's a largely passive undertaking and it cannot guarantee that you will be able to think theologically, never mind live out of a particular theological point of view. The trick with reading theology is to figure out (quickly) the difference between the good stuff and the dreck.

Doing theology (i.e., thinking, writing, or seeing theologically) is a rather more active, constructive undertaking. And, it can be far more demanding. It embraces intuitive and analytical skills that reading theology doesn't necessarily depend upon (although they are certainly a welcome asset). Doing theology involves seeing and understanding the world from a particular vantage point. It requires rigor, however, because while the connections are always there with what is happening around us, the connection between a particular theological point of view and the vagaries of life is not always lying there on the surface.

It's a process that is always imperiled by the temptation to rely on other ways of thinking as well. Those ways of thinking can be useful, of course. But there is a very real difference between the fruitful intersection of theology and, say, political or sociological analysis, and political or sociological analysis with a theological patina.

Doing theology also depends upon reading theology to save it from eccentricity and self-serving motives (assuming, of course, that you read theology worth reading). There is a thin line that is never quite visible between creative, uncanny theological intuition and mere novelty. (If you don't think that's true, I would invite you to spend a weekend with the American Academy of Religion.) The devil (literally) is in the details, of course, because from person to person that line can be drawn in very different places. That is why it is important to be clear about your own assumptions about God and the nature of God's work.

Then there is living a theology.

Promoting Laura Winner's new book, Still, Harper One's Mickey Maudlin makes a pointed observation:

One of the dirty little secrets of Christian publishing is that few authors actually talk about God—that is, God as the active and personal being engaged with our day-to-day lives. Most Christian authors unpack what the Bible says, what doctrine entails, what God's plans are, or what other historical figures did or said, and then apply these lessons and examples to today. But few authors come clean about their divine encounters (beyond their conversion experience), let alone feel any confidence in offering guidance on how we walk and communicate with God today. Christians teach that we have a personal relationship with a personal God, but few contemporary authorities explain how the "personal" part works.

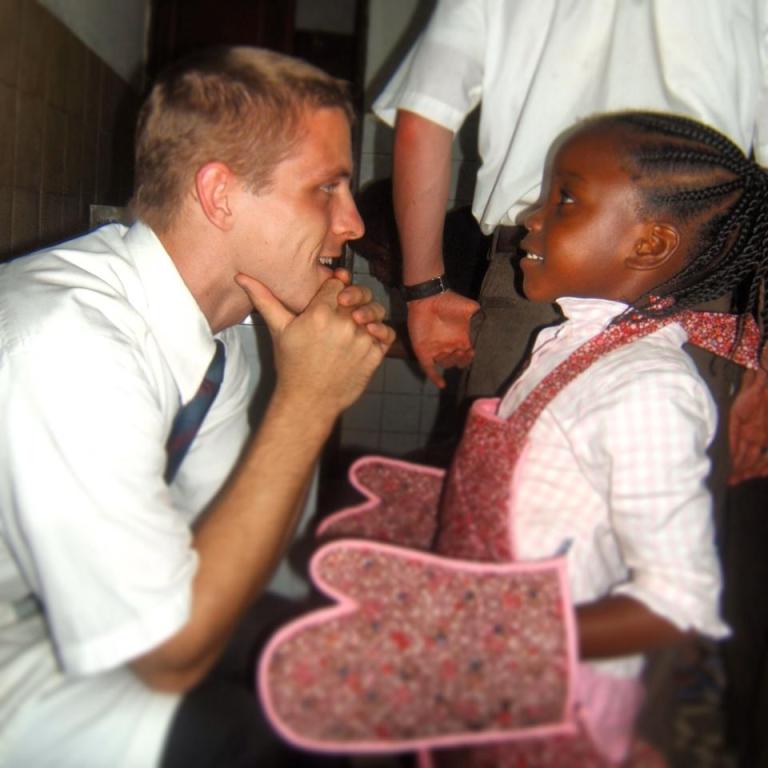

Maudlin is right. Living a theology requires an experience of God and that's a much more demanding affair than writing about it.

What surprised me two weeks ago in reactions to this column was just how difficult it is to get clergy to think and talk theologically about an issue, i.e., do theology—never mind talk about an experience of God. Some argued that there wasn't a theological observation to be made, but, frankly, I think that there is always a theological or spiritual point to be made, if you are alert to it.

So why is it so hard for us to talk about an experience of God and how that informs our view of the world? I am not entirely sure.

Some possible answers that occur to me are these:

- We read theology with seminarians more often than we teach them how to do theology. Doing the one does not guarantee that people can do the other and perhaps what is missing to some degree is a focus on practice and method.

- Some of the theology that we read with seminarians and candidates for ordination may be more deeply indebted to political and economic categories than it is to theology itself. There is a fine line between theology that speaks to political and economic considerations, and theology that serves as a thin veneer for political and economic arguments. And sometimes that distinction gets lost, even in the "professional" literature on the subject.

- Perhaps, the absence of theological sensibilities has to do with the fact that thinking theologically is neither what the church clearly expects nor rewards. I have been through the ordination process and I have watched countless others navigate it. It is rare for the people charged with that process to ask genuinely theological questions and still other times when theological questions are used to score political points.

- Perhaps somewhere between seminary and church we are seduced by the relevance of speaking in categories that are not theological at all. Ordained life can be a journey into estrangement. On the front end, the task feels like something everyone cares about. But the longer you work at it, the clearer it becomes that many people are not just uninterested, but hostile to theological concerns. Part of that, of course, is our own fault for failing to speak in clear, accessible categories. Some of the disinterest lies in our failure to "bring it home," explaining how theology changes the way that we live. But, frankly, those are not the only reasons—some disinterest and hostility is just that, disinterest and hostility. When clergy become alert to the authentic disinterest and hostility that is out there, it is tempting to look for other kinds of language to reconnect with the people around them. That is what makes speaking in political categories such a tempting substitute.

- Perhaps all of us are overwhelmed by the demands of church life that seem to have little or no bearing on the way we do theology. You can talk for a long time about the tasks clergy are expected to fulfill before you get to something that explicitly requires theological training, never mind a prayer life. Endless administrivia, building maintenance, conflict resolution, financial concerns, and pastoral care seem to crowd theological work to the margins of life in the church.

But the ability to do theology is not simply jeopardized by a failure to read good theology or to teach people how to do it. Nor is life in the real church, where doing theology is undervalued and overwhelmed by other demands, the only disincentive to speaking and thinking theologically.

Doing theology can also be jeopardized by the absence of an encounter with God. After all, those who live theology are the ones who do the best theology. The one question that seminaries and churches don't ask often enough is, "What is your experience of God?"

That, however, is a different kind of dirty little secret.

3/5/2012 5:00:00 AM