Abba Daniel used to say, "He lived with us many a long year and every year we used to take him only one basket of bread and when we went to find him the next year we would eat some of that bread." (Arsenius 17)

Abba Daniel used to tell how when Abba Arsenius learned that all the varieties of fruit were ripe he would say, "Bring me some." He would taste very little of each, just once, giving thanks to God." (Arsenius 19)

--from Sayings of the Desert Fathers

The desert mothers and fathers devoted themselves wholeheartedly to the ascetic practice of fasting. Asceticism essentially is about letting go of everything that keeps us from God and so is intended to be a journey toward authentic freedom. Desert ascetics kept their possessions to a minimum and fasting was practiced as a way of attending to the body. Fasting to the point of harm to the body was condemned, although there were certainly monks who did end up starving themselves to death.

Asceticism is always meant as a practice in service to freedom. When it becomes a competition or is oriented toward achievement, it no longer serves its purpose and becomes destructive. It can be another way we distract ourselves from the sacred presence in our midst. The fasting of Lent is not a second attempt at dieting when New Year's resolutions have failed. This is a distortion of the deeper meaning of this practice.

When we fast from food, we are called to become keenly aware of our relationship to food and to pay attention to our own hungers. When we fast from the comforts of our lives, the invitation is to stretch ourselves and become present to what happens when we don't have our usual securities to rely upon.

I have been contemplating what a life-giving fast looks like for me this Lent. I have chosen to fast from foods which aren't nourishing and only eating that which truly strengthens and vitalizes my body for my work in the world. As I sit down to a meal, I slow myself down, I ask is this what I am really hungering for? Does this feel truly nourishing?

The first story about Abba Arsenius above invites me to consider my relationship to food and what is "enough." Can I pay attention to my body's true hunger?

The second story calls me to truly savor the food I do eat, to linger over it, to celebrate the gift of nourishment, to taste and pay attention to whether that is enough.

Consider mealtimes as an opportunity for spiritual practice of checking in with yourself and being fully present to your inner dialogue around food. What happens when you prepare a meal in a loving way, sit down and breathe and give thanks, and then eat slowly, taking in the nourishment you need for service to others.

There are other dimensions to fasting in addition to our relationship with food. The freedom that comes with fasting is also from the things which weigh us down or keep us constricted. These might be things or stories, possessions or beliefs. Another story from the desert elders:

Abba Isidore of Pelusia said, "To live without speaking is better than to speak without living. For the former who lives rightly does good even by his silence but the latter does no good even when he speaks. When words and life correspond to one another they are together the whole of philosophy." (Isidore of Pelusia 1)

Abba Isidore's words above speak to different kind of fasting, fasting from false speech or ideas which keep us from truly living, fasting from that which doesn't truly nourish us in spirit. We all hold onto old ideas about ourselves that keep us limited in what we believe we can do with our lives. We all fill our lives with words as a way to avoid what is really happening within us - whether our own words and repeating old stories, or turning up the radio or television and being saturated with the words of others.

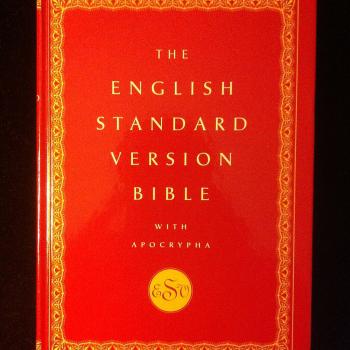

I know for myself, I absolutely adore books. They are essential to my work and writing and I can easily justify the many bookcases in our home overflowing with volumes of great wisdom. The problem becomes when I hear about a new book and I reach to purchase it (so easy to do now in these online times). I have learned to check in with myself, do I really need this? Am I avoiding deepening into my own wisdom by relying on the words of others? This is a delicate balance, because I deeply believe that books open up new worlds and I am firmly committed to my own ongoing growth. But like anything books can also have a shadow side when they tempt us into believing we need more information about ______________ (fill in the blank) to feel complete. Sometimes we buy more books as a surrogate for truly living what we believe those books to contain. At least I know I do that sometimes. The key is being fully present to ourselves and noticing where the hunger comes from.

The invitation from the desert elders here is first and foremost, to fully live. That will mean different things to each of us, but we have all had the experience of something bringing us alive. And we all have ways of avoiding that very thing.

What are the words or ideas that you cling to which are no longer nourishing and don't support you living fully? What is the fast you are being called to in these Lenten days?

3/12/2012 4:00:00 AM