As more of us care for aging parents, the Fifth Commandment might become more important for putting our feelings in perspective than for telling us how to act. Listen in as a member of the sandwich generation speaks honestly about caring for her aged father.

"I WAAAAAAAANT MY FATHERRRRRR TO DIEEEEE!!!" This, essentially, is how Sandra Tsing Loh begins a piece on the topic in the March issue of The Atlantic. It does not leave much room for doubt or nuance.

Don't be too harsh with her. With the increasing longevity that comes with good health care, people are living longer. At the same time, their last years are becoming more of a drain, often depleting their life savings and then, like the hand reaching out from the grave in an old B-movie, sucking up the savings of their children as well. As Boomers reach their senior years, eldercare issues are going to get more severe before they get better.

"Daddy Issues" deals with the way she handles the demands her aged father makes on her time and energy. She is brutally honest, even if she cannot be gracious and patient toward her father. Many others have thought some of the things she has. The difference is that others struggle against those thoughts, while she embraces them.

She explains why she would like Daddy to move on. "Never mind the question of whether, given that they have total freedom and no responsibilities, we are indulging our elders in the same way my generation has been famously indulging our overly entitled children. Never mind the question of whether there is a reasonable point at which parents lose their rights, and for the good of society we get to lock them up and medicate them. . . . I rant to myself: He is taking everything! He is taking all the money. He's taken years of my life (sitting in doctors' offices, in pharmacies, in waiting rooms). . . . That's right: my family is throwing all our money . . . leaving nothing for my sweet little daughters, with their thoughts of unicorns and poetry and dance, my helpless little daughters, who, in the end, represent me!"

She admits that "I will of course miss him . . . when he is dead," and that "in traditional China, with its notions of filial responsibility, my elders would be living with me in my home, or I in theirs." As you close in on the end of the article, you convince yourself that Tsing Loh is working up to revealing some epiphany, some insight into how much of her father is at work within her, and how she can never repay the debt of what he has given her. You expect her to somehow find moral enlightenment at the end of her struggle, or at least at the end of the article.

It doesn't come. Her ending is as soulless and amoral as the beginning. Discovery, yes, but no insight: "I can no longer think of my dad as my 'father.' But I recognize in him something as familiar to me as myself. To the end, stubborn, babyish, life-loving, he doesn't want to go to rehab, no, no, no." The conclusion of the article, then, is as much a non-happening as the greatly awaited demise of her father. No fanfare; no significance.

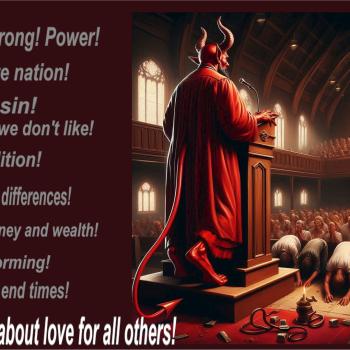

Missing from everything that I have ever read of hers (she is, by the way, literarily one of my favorite writers, whose every word I eagerly read) is G-d, and a theistic value system, any articulation of principles that are bigger than life. If she has one, her readers don't find out about it.

With religion or without, it is important—especially from the standpoint of the Judeo-Christian tradition—to credit Tsing Loh with what is most important: she does take care of her father. Together with her siblings she ensures that he has the necessary help to care for his health and well-being. She may want him dead, but much of the quality of his life today owes to her good deeds.

Herein is the irony. A religiously connected child might not behave differently. Tsing Loh's dad is not necessarily getting short-changed by the absence of a religious ethos in his family. Tsing Loh is the one who is coming up short. While her sentiments are horrid, she does not abandon her father. She complains, but she still does pay for his care, in cash and in time. Despite all her ratiocination, she cannot cut anchor from some subliminal sense of duty. She leaves the essay as she entered it: trapped between instinctive obligation on the one hand, and cold calculation on the other. Moreover, she has no way to even process the tension between them, some way to make sense out of being able to hold on to both at the same time.

A 19th-century sage, Rabbi Meir Leibush Weiser (known to traditional Jews by his acronym, Malbim), succeeds where Sandra Tsing Loh comes up short. He comments on Deuteronomy's recapitulation of the Ten Commandments. Unlike the version in the Book of Exodus, the later version appends what reads like a guarantee for those who honor their parents: "it will be good for you." Malbim explains that this is not an announcement of Divine reward to those who are obedient children. Rather, it addresses the mindset of those who find no need to honor parents. They often downplay the argument used most often to explain why children should honor parents: that parents gave them the most precious gift imaginable, the gift of life itself. The Bible, in part, bolsters our almost instinctive reaction of wanting to acknowledge and reciprocate any good that is done to us. In the case of parents, we never fully discharge that obligation because it looms so large.