- Trending:

- Pope Leo Xiv

- |

- Israel

- |

- Trump

- |

- Social Justice

- |

- Peace

- |

- Love

The 100 Most Holy Places On Earth

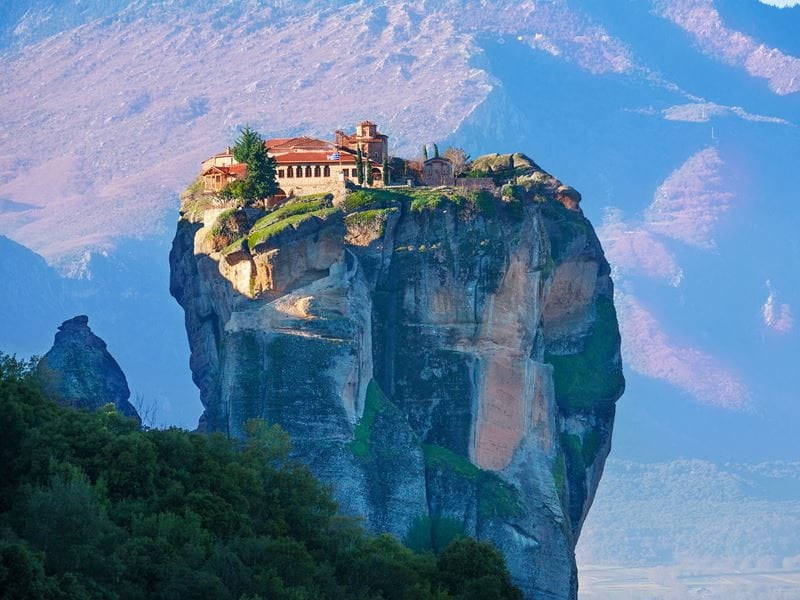

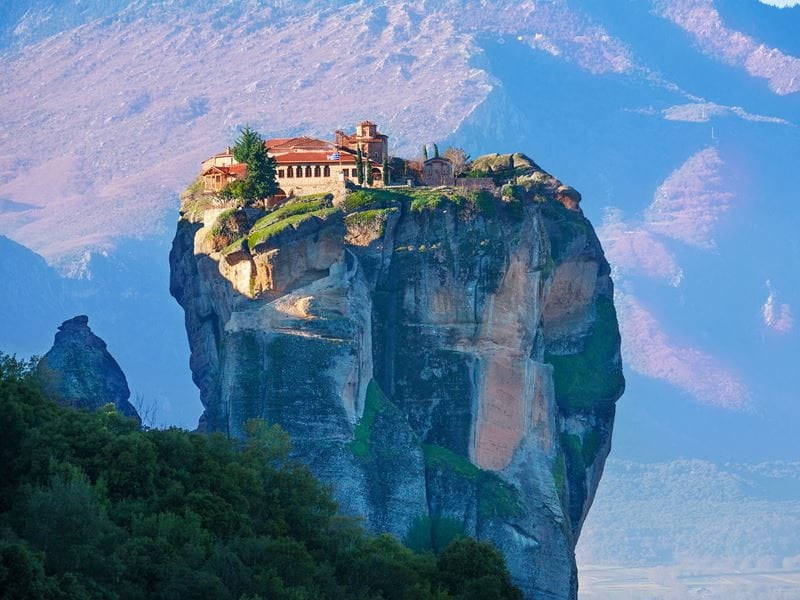

Metéora

Associated Faiths:

Greek Orthodox

Also frequented by religious people of many traditions, including other Low and High-Church denominations of Christianity.

Accessibility:

Open to visitors. Strict dress code: men must wear trousers and long sleeves, and women must wear a long skirt.

Annual Visitors: 2,000,000

History

According to tradition, in AD 935, a group of Greek Orthodox monks took refuge in the sandstone clifftops of Metéora—which means “lofty” (though it has also been translated “suspended in the air”). The monks were seeking to escape an invading Turkish army who threatened their lives. (Another invasion threatened the same area in the 14th century.) Accordingly, from the 10th century forward, these tall natural rock formations (some of which are as high as 2,070 feet) have been the home to innumerable Orthodox monks and nuns and, over time, 24 different monasteries have been bult atop the sandstone cliffs.

While monks are said to have inhabited the 60 million year old caves and “rock pillars” of Metéora since the 10th century AD, there is some disagreement as to when the very first permanent structure was built on the site. It is generally assumed that the oldest of the 24 monasteries located on Metéora—“The Holy Monastery of Great Metéoron” or “Megálo Metéoro”—dates to somewhere around AD 1344-1372. While no one knows for sure, what we do know is that, by the end of the fifteenth century, all 24 monastic structures had been built.

The inaccessibility of the location was by design. They were seen as a defense against attacks and intruders. However, the location of these “heavenly pillars” (as they have been called) meant that the monks who built them had to carry all building supplies up on their backs or by hoisting them up using ropes and nets. For centuries, even the monks made their way up to and down from the monasteries via ropes and nets or, at one point, with a series of rickety ladders that were lashed together in order to make the monasteries accessible. In 1920, steps were carved into the rock to make the hermitages more reachable. Today, a cable car makes it possible for visitors to ascend and descend the cliffs with ease.

During World War II, a number of the monasteries were bombed and looted. Since 1972, consistent conservation work has been carried out to restore and preserve these remarkable holy habitations, perched upon heaven’s pillars. As of 2023, only six of the 24 monasteries are open to visitors, and only three are actually used for monastic purposes—serving as the residence of just a handful of Orthodox monks and nuns.

Religious Significance

Not all “sacred spaces” are open to everyone. Some traditions, like Islam, only allow members of their faith to enter their most holy sites (such as the Dome of the Rock and many Mosques). Other faith traditions, like the Eastern Orthodox, restrict access to certain genders (such as Mount Athos or the space behind the Iconostasis, or “icon screen,” in Orthodox churches). And even others, such as The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, allow only the most faithful of their members to enter their most sacred sites (such as their Holy Temples, not to be confused with their churches or Sunday “meetinghouses”). Thus, space that has been declared “sacred” is sometimes deemed intentionally inaccessible to much of the world. Convents and Monasteries have often fallen into the category of the “inaccessible.”

While Metéora’s monasteries prohibited the visitation of women until 1921, their inaccessibility had a different purpose. It was designed to protect the monastics living therein from danger, from intruders, from those who would seek to take their lives. Curiously, commentators on Metéora have sometimes pointed out the spiritual parallels. Monastics enter monasteries to reject the world and live lives of holiness—removing all which might threaten them spiritually. The monks of Metéora built these monasteries to reject a fallen and dangerous world, which threatened them physically. While monasteries and convents are sacred space largely limited to those who have taken “holy orders”—therefore limiting their accessibility to the laity; it is worth pointing out that they stand as an invitation to all believers to be careful about the degree to which they allow the world’s influences into their lives. Metéora, with its fortress-like design, sends a spiritual message that worldliness and sin are dangers each must protect themselves from. Its cliff-top monasteries symbolically testify to the need to create or own spiritual fortifications so that we can traverse the sin-strewn paths of mortality without succumbing to the enticings of the devil. Thus, while what remains of Metéora is open to tourists today, its holiness is not found as much in the bombed out former monasteries as it is in the spiritual symbolism of the site.

Aside from the profound spiritual message of the design and location of the Metéora monasteries, they—like any Orthodox church altar—have their associated relics. Among the most important to survive the World War II bombings of Metéora are those found in the 16th century monastery of St. Varlaam. That monastery—being one of the few at Metéora still open—is said to house the scapula of St. Andrew and the finger of St. John. Thus, pilgrims who reverence those two saints may find a pilgrimage to this site additionally uplifting.

Metéora is an awe-inspiring and spiritually symbolic place of pilgrimage. The site is a constant reminder of the consecrated sacrifice for God that those who built these holy habitations had to make. It is an invitation to the practicing Christian to likewise be willing to suffer, serve, and sacrifice for Jesus. But Metéora is also a constant reminder of the need to spiritually fortify one’s life in the hopes that protections and blessings will be poured out from the very heavens which these lofty monasteries seem situated so as to almost touch.