Editors' Note: This article is part of the Public Square 2014 Summer Series: Conversations on Religious Trends. Read other perspectives from the Mormon community here.

As the editor of a publication dedicated to sharing the diverse experiences of Mormon women, I have had a front-row seat to the conversations Ordain Women (OW) has galvanized around women and the priesthood in the last year. I have heard from many women who attest that spiritual experiences as a result of prayer, temple attendance, and scripture study have inspired them to examine their relationship to the priesthood more carefully.

While many are at peace with current Church practices, for some this pondering has resulted in what they can only describe as "personal revelation" that they are called to priesthood ministry. And as Mormons, we shouldn't be surprised: ours is a faith that teaches that women and men share the priesthood; that reveres a divine Mother in Heaven; that once ordained women to heal by the laying on of hands and continues to engage women in acts of pastoral caretaking through Church auxiliary programs. That such history and doctrine would cause many Church members to consider the exclusivity of our male ecclesiastical structure seems only natural. While some may support female ordination on the basis of a secular feminist thought, many are also empowered by these very Mormon teachings and a belief that Church practices and doctrines develop through "continuing revelation."

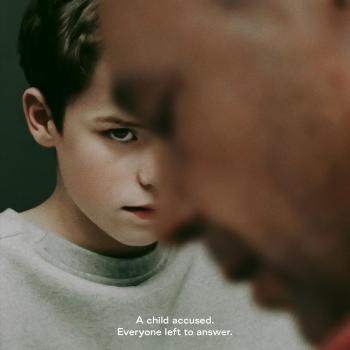

Yet in the wake of Kate Kelly's excommunication for her role in advocating for women's ordination, we are reminded of why this subject has been difficult for many church members to confront: in a religion which inextricably links priesthood with the simple fact of being a worthy male aged twelve or older, what options are available to women who develop a testimony of their own priesthood power and desire to officiate as equals with men in Church ecclesiastical structures? As members of a hierarchical institution, what good is personal revelation that does not align with the status quo but instead may anticipate the Restoration's unfolding? How seriously do we take the personal revelation of women when we have been taught that our spiritual lives are eternally mediated by men and maleness?

The recent statement from the Office of the First Presidency of the Church (which includes the LDS Prophet and two counselors also considered "prophets, seers and revelators" by LDS faithful) seems to be an implicit if not explicit response to Kelly's excommunication and the larger, much debated relationship between personal and institutional revelation. The statement in part declares that "Simply asking questions has never constituted apostasy. Apostasy is repeatedly acting in clear, open, and deliberate public opposition to the Church or its faithful leaders, or persisting, after receiving counsel, in teaching false doctrine."

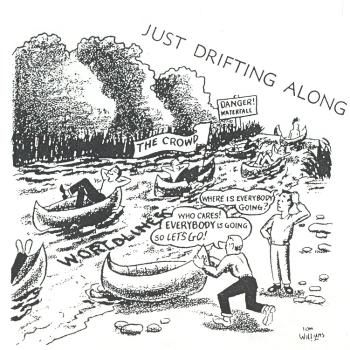

The LDS Church espouses a doctrine of continuing revelation that by definition requires a belief that there is grand revelatory potential that will move our faith beyond the status quo. But if the only people qualified to receive institutional revelation are male priesthood holders, how do the spiritual experiences and insights of women function within this framework? As the organization is currently structured, a woman can never be considered a "faithful leader" of the Church, which raises the question of how women can meaningfully participate in institution-wide change that results from personal revelation without engaging in some sort of advocacy. And on an individual level, how does the woman who feels called to priesthood remain faithful to her spiritual convictions while sustaining and obeying her ecclesiastical leaders? To remain silent betrays her sense of God-given personal revelation and risks compromising her personal relationship with deity. To speak is considered a betrayal of the institution and leaders she holds dear.

In my view, one of the most unsettling rhetorical strategies to rear its head in the last year is the accusation that any perspective that differs from or anticipates that of priesthood holders at the top of the hierarchical ladder is inherently oppositional. Rather than seeing most supporters of OW as temple attendees who have been inspired to contemplate women's relationship to the priesthood, OW supporters are depicted as acting in deliberate opposition to Church teachings and leaders. Members of OW are constantly challenged to prove or disavow their personal revelations and are instructed to repeatedly question themselves but never their leaders. They are told that faithful obedience is expressed by suppressing convictions they are permitted to feel but not publicly articulate, suggesting that any personal revelation which does not align with current practices must be "false doctrine" and dangerous to the body of the Church. The First Presidency statement does little to clarify the line between what constitutes unorthodox views from "false doctrine," but its assertion that those outside the strictures of ecclesiastical authority risk apostasy by openly agitating for anything different than the status quo is crystal clear.

I am hopeful that Church leaders outside the PR Department will begin to foster dialogue with women from a variety of backgrounds as the Church continues to seek revelation about women's place in the here and now and in the eternities to come. I believe that we all must grapple with questions being raised around women's ordination, but I see the current conversation as only one manifestation of cultural teachings and practices about women that must be addressed. Nevertheless, I'm thankful to OW for causing us to remove these issues from our spiritual pantries and examine them in earnest.

7/10/2014 4:00:00 AM