Editors' Note: This article is part of the Public Square 2014 Summer Series: Conversations on Religious Trends. Read other perspectives from the Progressive Christian community here.

I begin and end each day reading from the Bible. When I listen carefully, I hear God speaking to me through its words. I know most of its stories by heart. I've memorized many of its verses. I find in the gospels the story that I hope defines my life. When I want to know what God is like, or what God wills for my life, I turn to the scriptures. And yet, like Jacob wrestling with God, at times I wrestle with the Bible.

While my love for scripture has deepened over the years, so has my awareness of the questions we are right to ask when we read it. The questions begin on page one. Are the creation stories of Genesis 1 and 2 meant to accurately describe literal history, or are they poetic (chapter 1) and archetypal (chapters 2-3), intended to make majestic claims about God and creation and to teach us about the human condition? Was the story of Noah really written to tell us about a pre-historic man named Noah, or might it have been primarily written to tell us about ourselves and about the heart of God?

When we read through portions of the Law, we're right to ask, Did God really demand that a priest burn his daughter alive if she became a prostitute? Or that husbands must kill their wives with their own hands if their wives tried to lure them to worship any God but Yahweh? Did God really demand the death of every man, woman, and child among thirty-one kingdoms of the ancient Canaanites? Or take the lives of 75,000 Israelites as a punishment for David's sin of taking a census?

We might look at the wonderful promises found throughout the scriptures, words promising blessings if we do well and curses if we don't, and with Job, and Jeremiah, and others, ask, "If this is so, why do the wicked prosper?" And what do we do with over two hundred verses of the Bible where God permits the Israelites to sell their children into slavery, or to purchase slaves and even to beat them with rods provided they don't die within the first forty-eight hours of the beating? Does the subordination of women found in both Testaments reflect God's will for women?

Some claim that the Bible is inerrant, meaning that there were no errors in the documents that make up our Bible. Yet it is easy to demonstrate hundreds of errors and inconsistencies within the text of scripture. And—at the center of the debates that are dividing entire denominations—are the handful of scriptures that speak of some form of same-sex relationships really indicative of God's feelings about gay and lesbian people who wish to share their lives together?

All of these questions and more are raised within the text of a book that I believe God has inspired and which speaks profoundly to me and calls me to live selflessly, to forgive repeatedly, to pursue justice relentlessly, and to love God and neighbor continually.

When I was in college and later seminary, pursuing degrees in scripture and ministry, my assumptions about the Bible were challenged. This was a bit unnerving at first. Yet it was in these courses on the Bible that I eventually found keys to answering many of the questions I was asking about scripture. I learned that while God influenced or inspired the human authors, no one is precisely certain how. And while we often refer to the Bible as the word of God, that word is actually found within the words of real people who wrote from particular perspectives, in particular times, to address particular needs of their hearers. These authors, like the people who read the Bible today, brought with them to the task of writing their own assumptions about life and faith.

It was precisely in the mystery and tension between the Bible's humanity and its divine inspiration that we find the space to ask questions of the biblical authors. At the same time, it is in this tension that we're required to listen carefully for the word of God within the words of scripture's human authors.

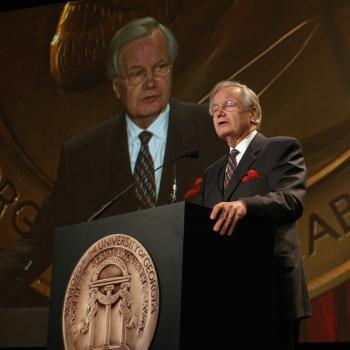

I wrote Making Sense of the Bible to help readers understand the kinds of things that most pastors learn in a first-year seminary course on the Bible. My hope was that it might help them, as it helped me, to resolve some of the questions they might have about the text while giving them the tools to hear God's words within the words of its human authors.

For a free preview of the introduction and first chapter of the book, click here.

6/18/2014 4:00:00 AM