Editors' Note: This article is part of a Public Square conversation on Billy Graham's life and legacy. Read other perspectives here.

I have always liked Billy Graham, even though he and I are different kinds of Christians and different kinds of Protestant Christians. He is a great preacher; I am a quiet preacher. He had a media parish; I have a bricks-and-mortar situation. He was a believer in heaven and hell; I only understand heaven and dislike hell's fire and brimstone. I am a universal salvationist; he is a little more partial. He believes in personal responsibility and private solutions; I believe in private solutions as well as governmental and structural justice. His idea of changing race relations is integrated seating at his revivals; mine is a living wage and raising the age for heavy sentences in prisons.

What I have liked about him is his energy. He really believes in what he really believes. When he says he wants a spiritual awakening for America—his main theme as an evangelist and an enthusiast for the gospel's power—he means it. He thinks Americans are spiritually asleep. So do I. He wondered about whether Jews could be saved. I am married to one. Even though he and I share a hope for an American spiritual alarm clock to ring loud and clear, one of us has a baseline tolerance, the other baseline fervor. We meet on this long continuum in our goal of a spiritual awakening. My path is to tolerate many routes to salvation and his is to tolerate fewer. The very gift of his energy and his ability to be a true believer get in my way along the Way.

I still like him. I have always loved to hear him preach. His voice is clear as a bell and his message the same. Complexity is not his friend. It is mine. Clearly the American people like clarity more than they like subtlety and nuance. Why else would we have just two political parties, each of which demonizes the other?

When Graham spoke to presidents, he knew that place beyond the party. Of course, he was better friends with Republicans than Democrats but he was trans-partisan. Like Oscar Romero, the assassinated Bishop of El Salvador, he believed in a profound separation of church and state. He believed that religion could advise the state, as long as it always knew it was larger than the state. His God was not absent from politics but larger than any one kind of politics. Romero also never wanted the state to be in complete harmony with the Catholic Church. He wanted to preserve the state's integrity in a larger place, where religion had its own integrity, supra-state. Likewise, Graham had a way of smiling his way above partisan politics and not making his faith or his church small.

A Southern Baptist, he also transcended denominations and pioneered media religion. We Protestants on the other side of the table were always "afraid" of media religion, fearing that it might make us look like the kind of Protestant who really believes what she really believes. We also thought we were a bit above the masses and that their salvation didn't matter as much as a finely hewn one. The words "class bias" come to mind, as though education was only something that happened at the finer institutions where subtlety and nuance was subtly taught, with nuance. The word "region" also comes to mind, as though notions held widely in the Northeast would always be smarter than notions held widely in the South—let alone ideas produced for mass consumption.

Graham honored our common faith by believing, finally, that people are good. I thought of him just last month when my congregation produced the Rev. Al Carmines' musical, The Bonus Army. One of the most powerful songs in that musical is sung by a veteran who has come to Washington to collect his bonus for fighting in the First World War. "People are good, Honey," croons the actor who plays the part of "Billy." It is one of those songs you can't get out of your head. "People are good, honey." Graham believed people were sinful and in need of salvation in a very hopeful way. He is finally comic, if I am finally tragic. Right after Billy sings this song, he is shot by his own government, for coming to pick up his check.

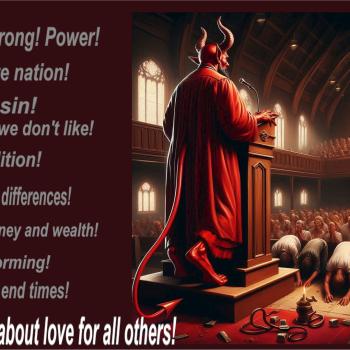

I like Graham because he lacked vitriol. He remained optimistic, despite the evidence so well supplied by the movement he spawned. The Religious Right today has very little in common with Billy Graham. It surely uses the media well and believes aggressively in private solutions and private responsibility and personal salvation and bootstraps for people who don't even have boots left. But Graham had love in his heart. His cultural and religious heirs do not.

11/12/2013 5:00:00 AM