The term "incarnation" means "taking on flesh," with an emphasis on the kind of meat that one usually associates with animals. Both in the biblical Greek (sarcothenta, from the root sarx) and the Latin (incarnatus), the Nicene Creed emphasizes that Jesus didn't just appear to have a body (the claim of a heretical group of the 4th century, the Docetists, whose name comes from the Greek verb "to appear"). He was real flesh and blood, the stuff animals are made of.

John's gospel emphasizes this point, probably in response to those who claimed that Jesus was not God: "the Word became flesh [sarx], and moved his tent in among us" (or "made his dwelling among us") (1:14). John begins the gospel with an extended commentary on the Logos, the Word. Interestingly, John seems to be borrowing from more ancient Greek religion in associating Christ with the Logos, the order in the universe. Consider, for example, Kleanthes' Hymn to Zeus, which Paul quotes in his speech before the Areopagus in Acts 17:

For under [thy thunderbolt's] stroke all nature shuddereth

and by it thou guidest aright the universal Logos

that roams through all things . . .

Describing God as the one who orders the world through a divine Logos is consistent with what one would have found among pagans and Stoics in both Greece and Rome for centuries before Christ.

The real point of departure for Christianity is the claim of the incarnation, which would have been seen as ridiculous in the classical world. Plato, for example, held that there was a kind of ladder of being, with spirit at the top and flesh at the bottom. God's taking on flesh would have appeared philosophically incoherent. Yet this claim of incarnation is precise, both in John's gospel and in the Nicene Creed. God took on human flesh by becoming incarnate by the Holy Spirit with the cooperation of the Virgin Mary (Marias tes parthenou).

An important feature of the Greek version, which is lost in both the Latin and English versions (though present in Italian), is that the incarnation is a product of both the Holy Spirit and Mary together. The Greek does not suggest that the Holy Spirit is the mover while Mary is a passive recipient: it is translated simply "he was incarnate of the Holy Spirit and the young girl Mary" (σαρκωθέντα κ Πνεύματος γίου κα Μαρίας τς παρθένου). Mary cooperates in the work of the incarnation; she is an active participant in bringing God into the world.

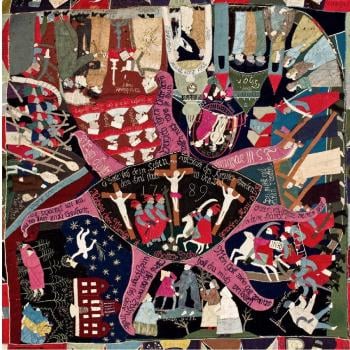

That, to me, is a beautiful image. For as the story of the nativity illustrates, God's entrance into the world is not by force or fanfare; it is quiet, almost absurd, heralded by riding on a donkey through dusty roads to a place where there's nowhere to sleep safely.

There is, I think, a spiritual truth embedded in this profession of faith. God chose Mary for a special role in the economy of salvation, but we believe too that God extends an analogous invitation to all his creatures to bring forth some concrete good with their lives, to "incarnate" Christ in their lives. Gerard Manley Hopkins put it well:

I say more: the just man justices;

Keeps grace: that keeps all his goings graces;

Acts in God's eye what in God's eye he is—

Christ—for Christ plays in ten thousand places,

Lovely in limbs, and lovely in eyes not his

To the Father through the features of men's faces.

Hopkins sees each person living fully as the creature God made him or her to be, "justicing," as it were—becoming an act of justice (rightness in the world God has made) and thereby becoming Christ in God's eyes. Hopkins proposes that there is a kind of incarnation that happens when we are most fully ourselves, responding to God's invitation to freedom in the manner of the young girl from Nazareth.

12/2/2022 9:05:38 PM