By Talia Hava Davis

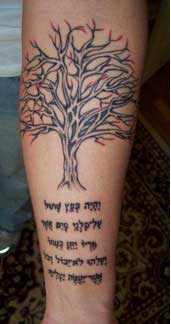

Have you ever heard that if a Jew gets a tattoo, they can't be buried in a Jewish cemetery? Isn't it amazing how some myths become fact? To quote the movie The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance -- "When the legend becomes fact, print the legend." The fact is, Jewish cemeteries won't refuse your body if you have a tattoo... but, oy! Your Jewish mother would be so farshadet (Yiddish for wounded, hurt) and your Jewish tush is af tsores (Yiddish for in trouble)!

Have you ever heard that if a Jew gets a tattoo, they can't be buried in a Jewish cemetery? Isn't it amazing how some myths become fact? To quote the movie The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance -- "When the legend becomes fact, print the legend." The fact is, Jewish cemeteries won't refuse your body if you have a tattoo... but, oy! Your Jewish mother would be so farshadet (Yiddish for wounded, hurt) and your Jewish tush is af tsores (Yiddish for in trouble)!

So where does this prohibition come from in Judaism? Why is it such a big deal? I asked six Jews, rabbis and lay leaders, what their thoughts were. I asked them for their understanding or translation of Leviticus 19:28, which is the section of the Torah that is commonly referred to when we talk about tattoos. I also asked them why they felt Jews shouldn't get tattoos, how they feel toward Jews who have tattoos, and if they feel that getting a tattoo is disrespectful to the members of the tribe who survived the Holocaust.

Now I know that last question might seem like a non sequitur but in my research I found many statements like this one from Holocaust survivors:

"They might as well be walking around with a Nazi flag," said Minneapolis resident Leo Weiss, 84. "It shows a lack of respect for Holocaust survivors, Jews and non-Jews alike. It's an insult to us. It's offensive to people who suffered under the Nazis and lost our loved ones." (Minneapolis Star Tribune)

Our ancestors who survived the Holocaust were forcibly tattooed; it was beyond their own choice. They saw it, rightfully so, as a symbol of the oppression of the Nazis and the loss of their own rights as human beings. Why then should young Jews be making this choice to voluntarily get tattooed when we, as a people, have such a history putting ink to skin? Another Holocaust survivor put it well:

"To me it just means we can make our own decisions now," says Steven Ross, a 73-year-old tattooed Auschwitz survivor and a driving force behind the Holocaust Memorial near Faneuil Hall. "In a few more years, there won't be any more survivors left," he says. Then, the only Jews with tattoos will be the ones who asked for them. (Boston Globe)

I don't think parents will ever be happy when their child comes home with a tattoo. I know that my liberal and open father is still not thrilled, eleven years later, that I got tattoos in college. But I personally find that tattoos can be expressive reminders of important things. I'm not advocating becoming a Post-it Note, but I find my tattoos meaningful. My only advice? Get it checked by a rabbi and be sure you know what you are doing. Nothing worse than a misspelled Hebrew tattoo...

Our responses are from:

Reb Bahir Davis, a post-denominational rabbi based in Lafayette, Colorado.

Rabbi Yossi Serebryanki, a Chabad rabbi, shliach of the Rebbe to Denver.

Liz Polay-Wettengel, the manager of Internet initiatives for Combined Jewish Philanthropies in Boston.

Matthue Roth, an author and associate editor at My Jewish Learning and co-founder of G-dcast.com.

Ezra Shanken, Senior Manager of the Young Adult Department and Major Gifts of the Allied Jewish Federation of Colorado.

Monica Rozenfeld, a freelance writer and founder of the edgy, Jewish culture blog The Jew Spot.

Twitter: I also put the word out on Twitter about tattoos and got a variety of responses. I had a nice conversation with one guy (in 140 character bursts).

Reb Bahir Davis

B'H

B'H

Leviticus 19:28: "You will not make any cuttings in your flesh for the dead, nor imprint any marks upon you: I am the LORD." There are two parts to this verse. The first one refers to a mourning process. In some cultures, when a family member dies, people would make cuts in their body as a sign of mourning. The first part of the verse refers specifically to that practice. It therefore does not come into the question of tattoos. The second part of the verse is more complicated. It is possible that it is a "Binyan ab mi-katub ehad" (application of a provision found in one passage or earlier part of the verse only to passages or parts of the verse that are related to the first in content but do not contain the provision in question.) If this refers to the first part of the verse then the words "for the dead" can be implied in the second part of the verse. There is another possibility called "Kal VaHomer." This means that if the first part of the verse is true, how much the more so is the second part true. In other words and with a good rabbinic approach, the answer is that it could refer to modern tattoos or not.