Editors' Note: This article is part of the Patheos Public Square on the Future of Faith in America: Catholicism. Read other perspectives here.

Have you ever watched a flock of birds flying in one direction, then seeing the way a few birds will start moving in another direction, until the entire flock is following them? The change in directions is probably predictable by some kind of algorithm, but to our eye it can appear capricious, free — like birds themselves.

I read the latest Pew Research Center study of America's religious landscape just before reading a story about The China Religion Survey 2015, released by the National Survey Research Center (NSRC) at Renmin University of China. I'll focus on two points to contrast what is happening in religious adherence in these two global superpowers:

- In the United States, the number of Catholics is declining and the number of the unaffiliated is on the rise.

- In China, the Catholic Church is getting younger, meaning it is drawing increasing numbers of young people.

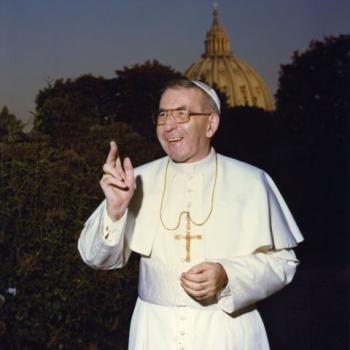

These movements appear to be in opposite directions: Catholicism is growing in China (along with Islam and Protestant Christianity) while it is in decline in many parts of the United States (though very certainly not all.) This is to be expected: over the past century, there has been remarkable flux in where the Church is prominent, but it nevertheless its share of the global population has been consistent.

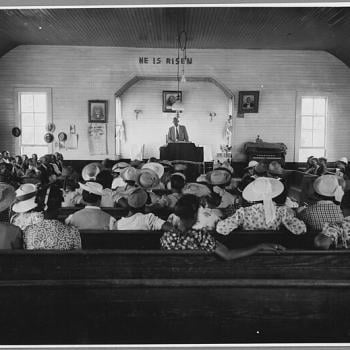

What we are seeing both in the United States and around the world, including the incredible growth of the Church in Africa and Asia over the past century, are the effects of rapid cultural change. Cultural change has an effect on both the macro- and micro-levels of society: they impact public policies as well as conversations between neighbors. Sociologist Peter Berger noted many years ago that religious convictions thrive in contexts where there is community, and one implication of that phenomenon is that when communities change, so does the landscape of religious belief.

None of that, of course, has anything to do with the truth claims embedded in a religious tradition. Catholicism is a faith tradition with a long history of reflection on the relationship between faith and knowledge, from the philosophers-become-apologists of the earliest centuries to the scholastics of the middle ages to the scientist-priests of the 20th century. It has had high moments and low moments, to be sure, and it has certainly been embedded for both good and ill within different cultural contexts. That the Church is changing is hardly cause for concern; the question is always whether that change is reflective of its fundamental mission as given by Jesus in the beginning, and sustained by the Holy Spirit in the present.

No theology can change the truth that hindsight is clearer than foresight, even for a community that discerns a God present in its midst and manifest in its sacramental life. It is clear in hindsight that much of Catholic history has seen a strong reliance on the connection between culture and faith, and that the connection can sometimes compromise what is most important. The cultural expressions of ritual — moving as they can be — can sometimes overshadow what is fundamentally an invitation by a loving God into relationship for the sake of making the world beautiful. Alternatively, the decline of those cultural expressions, due to a changing religious landscape, can feel like the death of faith itself.

History teaches us otherwise. From the earliest disputes between Jewish and Gentile Christians, to the explosion of religious art in the middle ages, to the missionary movements in the Age of Exploration, to the young and vibrant churches in Nigeria and the Philippines; China and the Democratic Republic of the Congo; Stockton, California and Brownsville, Texas — the Catholic Church has grown and thrived by drawing from the deep wells of its sources: scripture, the sacraments, its liturgical life, renewed by communities of people that encounter the gospel anew. En los Estados Unidos, la comunidad Hispana se renovará nuestra Iglesia.

None of these reflections changes the fact that there are significant pastoral challenges facing Catholic leaders of the early 21st-century United States. We must stem the loss of second- and third-generation Hispanics; we must do a much better job of ministering to young people; we must develop stronger catechetical programs for children and their largely uncatechized parents. The landscape is certainly changing, but if the Church is to be part of that landscape it must do everything it can to turn greater attention to its younger members. A new missionary era is upon us.

7/15/2015 4:00:00 AM