As an evangelical Christian who is also steeped in the deeply secular culture of academia (having spent nine years attending and going on seven years teaching at secular colleges and universities), the ability to rationalize and intellectualize my beliefs has proved an essential part of my Christian walk. From the moment I stepped onto the wonderfully-diverse campus of Johns Hopkins University as a freshman back in 2002, my Christianity—to which, at the time, I was 100% sold out spiritually and emotionally and 0% equipped to defend—was questioned from all directions. Through encounters ranging from good-humored and curious to truly hostile challenges posed by a Muslim suitemate, an atheist tennis partner, my roommate’s agnostic boyfriend, and countless professors on campus, I quickly realized my beliefs would need to shape up in the brains department or ship out. So the development of a scholarly faith–one affirmed by research, critical inquiry, and the great influence of respected theologians, historians, linguists, archaeologists, scientists, and any other number of intellectuals both within and outside of religious studies—was indeed born out of necessity. Never once in my Sunday School classes did we study apologetics. In fact, I’d never even heard the word. I had only my meticulously hand-written Bible verse notecards carefully taped to my dorm room desk to attest to my knowledge of the religion I had professed adamantly since a sixth grader at my Baptist church’s Vacation Bible School.

As an evangelical Christian who is also steeped in the deeply secular culture of academia (having spent nine years attending and going on seven years teaching at secular colleges and universities), the ability to rationalize and intellectualize my beliefs has proved an essential part of my Christian walk. From the moment I stepped onto the wonderfully-diverse campus of Johns Hopkins University as a freshman back in 2002, my Christianity—to which, at the time, I was 100% sold out spiritually and emotionally and 0% equipped to defend—was questioned from all directions. Through encounters ranging from good-humored and curious to truly hostile challenges posed by a Muslim suitemate, an atheist tennis partner, my roommate’s agnostic boyfriend, and countless professors on campus, I quickly realized my beliefs would need to shape up in the brains department or ship out. So the development of a scholarly faith–one affirmed by research, critical inquiry, and the great influence of respected theologians, historians, linguists, archaeologists, scientists, and any other number of intellectuals both within and outside of religious studies—was indeed born out of necessity. Never once in my Sunday School classes did we study apologetics. In fact, I’d never even heard the word. I had only my meticulously hand-written Bible verse notecards carefully taped to my dorm room desk to attest to my knowledge of the religion I had professed adamantly since a sixth grader at my Baptist church’s Vacation Bible School.

But thankfully, I had the Spirit and the good sense to not give up. Instead, I read through the downtown Baltimore Barnes & Noble’s Religion section; watched videos and devoured articles online; talked to and debated with people who disagreed with me on points ranging from evolution to the trinity to the accuracy of the Gospels; and signed up for classes like “Judaism and Christianity in Conflict” (taught by a rabbi) just for the opportunity to see an alternative view, test it out, and take what proved good if it was there for the taking. And most importantly of all, I read my Bible for the first time, all the way from “In the beginning” to “Amen.” I played devil’s advocate at every opportunity, and basically, from that freshman year on, my faith was and continues to be forged and affirmed via trial by fire. Words like “doctrine” or “tradition” suggesting a priori authority serve only as red flags for me to inspect more closely.

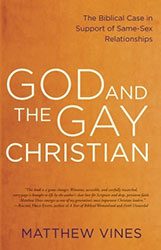

Which is why I was so excited to read Matthew Vines’ controversial God and the Gay Christian: The Biblical Case in support of Same-Sex Relationships. Gay marriage, along with Creation, abortion, the death penalty, and feminism is one of the subjects I have gone through a period of near-obsession over in terms of determining a defensible biblical standpoint, one founded in my own Spirit-led interpretation of the text and supported by the best of contemporary and historic scholarship. Though I do not personally identify as homosexual as Vines does, I do feel that we share some motives in our interest in the subject: Like Vines, I have several homosexual friends—some Christian—who are in what appear from the outside to be happy, content, faithful, monogamous relationships. Like Vines, I have seen homosexuals treated poorly by Christians: rejected by Christian friends and exiled from Christian families. Like Vines, I have witnessed gay Christians leaving the church over the response they received after coming out. And like Vines, my experiences led me to some questions: If gay relationships are sinful, why do the gay people I know who are in relationships—particularly in the cases of those couples identifying as Christian—report feeling fulfilled and satisfied (traits I never have identified with long-term indulgence in sin)? When the Bible condemns homosexuality, is it even referring to such relationships? Is homosexuality innate, and if so, how does that reconcile with creation “in the image of God”? Does the Bible describe homosexuality as different from, worse than, more resilient than other sin? And if homosexuality is a sin, how might the church do a better job of addressing it with grace?

To be clear, my own independent research—which began with Robert Gagnon’s The Bible and Homosexual Practice: Texts and Hermeneutics—and led me through works by both conservative and liberal scholars, left me affirming the “tradition” of exclusively male-female marriage as biblical, but, as with all of the particulars of my faith—and by “particulars” I mean any element not relating to the fundamental salvific element of belief that Jesus Christ died for our sins—I hold this position with an open hand, prepared for evidence or new Spirit-led revelation to guide me differently. And it was with such an open hand that I entered Matthew Vines’ text. As I cracked the first page, I let myself wonder if maybe I’d missed something, if maybe Vines—as the accolades he has received from various Christian leaders and writers express—knew something two millennia of Christian thinkers didn’t, if maybe he was led by the Spirit to open evangelicals’ eyes about homosexuality. The title of his book alone could leave a reader awash in curiosity.

I was especially eager to begin God and the Gay Christian as well because—though Vines has no formal credentials and though his personal stake in the matter as an open homosexual potentially weaken the claims of the text from the get-go—the evangelical church, before Vines’ book was even released, already felt so personally threatened by what he was going to say that The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary president Albert Mohler organized a formal response in the form of a free e-book to be released simultaneously with God and the Gay Christian. Several pages into Vines’ text, I saw why.

God and the Gay Christian is compelling. It is compelling because of Vines’ straightforward and matter-of-fact writing style, his ability to make the complex subjects of Bible translation and biblical history and cultural contextualization appear simple and comprehensible. It is compelling because of Vines’ excellence at weaving personal experience throughout textual exegesis. It is compelling because Vines is a unique voice: a self-proclaimed evangelical who claims avowed faith in the authority of the Bible and yet advocates a position traditionally deemed so liberal. And it is compelling because Vines presents his case for the biblical validation of homosexual marriage as a foregone conclusion, one which, if we would just do a little more research or look at our traditions from a slightly different perspective, will become imminently clear. His ability to make scholarship accessible and his personal testimony as an evangelical Christian who earnestly insists he is only interested in the truth (supported by the additional testimonies of his evangelical parents’ journeys to affirming gay marriage as biblical) could easily, I believe, prove incredibly convincing to a generation of readers whose world is already telling them that homosexuality is acceptable. It will validate what the culture has already validated for them, make them feel intelligent and informed in the process, and provide them a version of Christianity that is just a little less challenging to maintain, defend, and live out in today’s world.

For example: As I mentioned, my interest in apologetics began as a young college student. To be specific though, the first text that sparked this interest was The Case for Christ by Lee Strobel. The appeal for me in this book was that the writer was a former atheist convinced “by the evidence” to become a Christian; that he took what, at the time, appeared to me to be a rigorous approach to scholarship (interviewing experts in various fields about the accuracy of the Gospels); and that he wrote with a colloquial, to-the-point voice that left me with the impression that the conclusions reached were not only simple but obvious to anyone willing to do a little studying. The style of this one book alone revolutionized my approach to my faith. I now know that there are much more scholarly sources available to validate Jesus’ divinity, but I also know that there is no definitive proof of this divinity that has been found in an archaeological dig or an ancient extra-biblical text. Mystery is part of faith as well, and the danger of popular versions of apologetics (which for the most part are wonderful and useful gateways to deeper research for readers) is that they oversimplify, making leaps in logic that evidence does not truly account for, refusing to acknowledge what can’t definitively be known but through faith, and depending on just enough scholarly authority to appear irrefutably credible to lay readers.

And that is ultimately what I struggled with in Vines’ work. As the SBTS response points out, by centering his argument on refuting the six primary “clobber passages” in the Bible about homosexuality (Genesis 1:26-28, Genesis 19:4-5, Leviticus 18:22, Romans 1, I Corinthians 6:9-10, and I Timothy 1:9-10), he risks losing the overarching biblical narrative. By name-dropping a few key evangelical intellectuals (John Piper, Tim Keller) while depending predominantly on liberal revisionist sources for his research, he creates the effect that both camps’ views might be simply reconciled and that his work depicts a bridge. For readers who want to believe homosexuality is affirmed by the Bible, for Christians who are on the fence and find it challenging to continue to defend the church’s traditional position, even for seasoned Christians who haven’t bothered to delve into the myriad work by scholars un-cited by Vines who do not ultimately affirm gay marriage, there is a great possibility that this book will persuade.

What I liked most about God and the Gay Christian is that it sent me back to the Bible. When Vines cited a passage and suggested a context or a meaning I hadn’t considered, I immediately launched my YouVersion app to double-check different translations. Vines also sent me to the library. When he mentioned an historian or linguist I hadn’t read, I looked them up and now have a loaded-down-Amazon-shopping-cart’s worth of sources en route to my house to investigate firsthand. I liked God and the Gay Christian because it got me more engaged with my faith, inspired me to think, and pushed me to seek out the knowledge and the wisdom to better articulate my beliefs about the biblical position on gay marriage. Evangelicals are not usually known as intellectuals. God and the Gay Christian might push us to be more so.

What I didn’t like—and there were a variety of points I disagreed with, which have been dealt with in detail in the SBTS response and elsewhere, but what troubled me the most—was that ultimately, in his effort to affirm homosexuality, Vines throws women under the bus. I am certain this was not Vines’ intent, but here is how I, as a woman, read his argument: if contextualized appropriately, the problem the biblical writers have with homosexuality is either that it represents excess (akin to sins like gluttony or adultery) or that the crux of the sin is that it is inappropriate for men to be taking the “womanly” position during intercourse, not because of reasons related to anatomy but because to be like a woman is to take on an inferiority that is insulting to one’s manhood. While Vines cushions the latter point by saying that it was the culture at the time that believed in the inferiority of women, what he is actually saying is that the biblical writers believed in the inferiority of women, which is to say that if you believe their writing is the inspired word of God, as I do, then it is not just Moses or Paul but God Himself Who promotes a hierarchy of value in male-female relationships, a claim which is certainly not tenable for me or any other evangelical, I would imagine (different gender roles, perhaps; a superior-inferior dynamic, absolutely not). As a woman reading Vines’ interpretation of the Sodom and Gomorrah narrative, for example, a reading which depends on it being a lesser sin to give one’s daughter to be raped than to have one’s male guests raped (i.e., treated like a woman), every what-the-heck alarm in my body was sounding. That’s not the God I know. And it seems unlikely as well that the Hebrew people (who were aware of God’s high valuing of and ideal for women as established in the Creation account in Genesis) would be ranking sin in this way. I don’t think they were. I think Vines’ interpretation is wrong and dangerous in its implications for women in the church, and it was troubling to me that a man so clearly interested in extinguishing discrimination sees no issue in breeding confusion in terms of God’s view of women in his effort to promote God’s acceptance of homosexuals. This is a point I have not seen noted often enough or dealt with thoroughly enough in the criticism of God and the Gay Christian.

But, with that said, I’d also like to end with this: After reading Vines’ book, I immediately downloaded the SBTS response. As I anticipated, it makes all the necessary arguments to refute Vines’ claims and will prove helpful for anyone who, after reading God and the Gay Christian, seeks out a refutation. The response shows that the evangelical church takes its position seriously and can defend it readily and thoroughly. I will say this though: if the evangelical church really wants to get a counter message out there, an e-book written by traditional authority figures, with all the theological jargon of their field, for an audience already familiar with the Bible and its traditional interpretations is not the way to go. The SBTS response will affirm the audience of evangelicals who have already—with or without reading God and the Gay Christian—firmly placed themselves in the anti-Vine camp. The readership Vine has targeted though, the group to which I believe he will most appeal—young evangelicals, on-the-fence evangelicals, evangelicals with gay friends whom they love deeply, or evangelicals struggling with homosexual desires themselves—will likely find the response opaque, stilted, and stylistically out of touch. A YouTube video response, a social media campaign, or a public conversation with Vines himself even (he responded to one of my tweets about his book within minutes, so I know he’s up for dialogue!) might be more effective for this audience. Also, the near complete absence of young evangelicals writing and speaking for the traditional “non-affirming” position on homosexual marriage is notable. Where are these voices? And where are the evangelicals who have struggled with homosexuality and overcome? How about the lay evangelicals who have done the scholarly legwork to refute Vines’ claims? Or the evangelicals who are even just willing to have graceful public conversation directly engaging with Vines’ ideas? Do these voices exist? If so, why aren’t they speaking out more loudly and more visibly? Their silence at moments like this is deafening.

The evangelical church is right to be concerned about God and the Gay Christian. It will hit home with its target audience. And unless the church responds to this same audience in a language and with voices that will appeal to and show an understanding of their perspective, Vines’ claims may very well become the theological foundation for the next generation of evangelicals’ view on marriage.

To read an excerpt from God and the Gay Christian – and to view a live chat with the author – visit the Patheos Book Club!

Amber M. Stamper holds a Ph.D. in English (Rhetoric and Composition) and is an Assistant Professor of Language, Literature, and Communication at Elizabeth City State University in North Carolina. Her research and publications center on religious rhetoric and communication, especially issues of Christian evangelism and the digital church.

Amber M. Stamper holds a Ph.D. in English (Rhetoric and Composition) and is an Assistant Professor of Language, Literature, and Communication at Elizabeth City State University in North Carolina. Her research and publications center on religious rhetoric and communication, especially issues of Christian evangelism and the digital church.