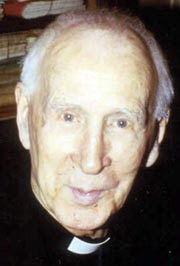

A Brief Look at Henri de Lubac: Recapturing the Catholic patrimony

Henri de Lubac—French priest, scholar and cardinal—stands at the center of the Ressourcement movement in Catholic theology. While he certainly was not the progenitor of Ressourcement, there seems to be little doubt that de Lubac is its most important and influential exponent. When one attempts to lay hold of the very heart of Ressourcement, one can do no better than to begin with de Lubac’s theological enterprise. Remarking on the manner in which de Lubac’s first book, Catholicisme (1938), affected his own theological orientation, Pope Benedict XVI—then Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger—wrote in 1988: “(De Lubac) makes visible to us in a new way the fundamental intuition of Christian Faith so that from this inner core all the particular elements appear in a new light…Whoever reads de Lubac’s book will see how much more relevant theology is the more it returns to its center and draws from its deepest resources.”[1] Indeed, one can extend this sentiment to the whole Lubacian corpus.

What characterizes Ressourcement is that which characterizes the entirety of de Lubac’s thought: the conviction that the treasury of Patristic theology does not wear thin along the historical terrain traversed by Christianity and that Christianity cannot meet the exigencies of modern times without rediscovering its essence through a return to its sources in the Church Fathers.

Henri de Lubac entered the Jesuit order in 1914 and immediately gravitated toward a study of the Church Fathers, particularly of Origin and Augustine, during his formation. He was also quite drawn to the works of Rousselot and Blondel, and to a lesser extant Maréchal, all of whom he read alongside the staple Neo-Scholasticism of the religious reformation. What these authors addressed and assailed in the largely theoretical sphere became for de Lubac a concern in the practical and social sphere: the gradual disappearance of the sacred in every element of human existence. In a rarely quoted essay from 1942, de Lubac writes: “Now, basically, this world is not by itself either sacred or secular, for it receives its significance only through man. It can become one or the other according to the way in which man behaves in its regard.”[3]

At the heart of de Lubac’s theology is a concern to re-establish in the consciousness of humanity the Christian principle that the sacred—the presence of God’s saving activity—is not some foreign, invading force in an otherwise mundane, secular world. Rather, nature is always incomplete and unfulfilled without the gratuitous sanctification wrought by grace, and it is peculiar to human nature to release the full splendor of the grace given to it. For de Lubac, as for the Fathers, anthropology and ecclesiology are fully intelligible only in light of one another.

Marking de Lubac’s first two works (which can rightly be described as a sort of the programmatic for the Ressourcement movement) is his utter dismay at the secularization of modern European society. His first book, Catholicisme (1938), was published in Yves Congar’s Unam sanctam series. Illumining the historical, social and personalist understandings of the Church with constant reference to the Fathers, it contains the seeds for all of de Lubac’s subsequent thought, and was extensively read and translated throughout Europe. While primarily an historical study on the social character of the ecclesiology postulated and developed by the Fathers, it is undeniably clear that in it de Lubac is seeking to underscore the pervasive presence of grace in the world and the corresponding destiny of all humanity in Christ through the Church.

With the 1946 publication of his Surnaturel and its criticism of the neo-Scholastic theory of “pure nature,” de Lubac became the eye of the theological storm turning throughout Catholic Europe. De Lubac took issue with the hypothetical model of pure nature, which postulated a hypothetical natural end or telos for humanity if grace was not given, in part due to its absence from the patristic and medieval traditions of the Church. He also noted what he saw as an increasing separation between the secular and sacred, the root of which was not modern philosophy or political circumstance, but the dry, logic based polemic of Neo-Scholasticism against Baianism on the one hand, and ‘Cartesian’ rationalism on the other. Neo-Scholasticism, claimed de Lubac, was implicitly sanctioning the efforts of post-War Europe to banish religion and faith from the public sphere. In portraying nature as an autonomous system capable of attaining its end by means of its resources, Catholic theology, under the guise of ‘Thomism,’ was conceding nature—and humanity itself—to secularism.

The Ressourcement movement, therefore, was not simply an effort to recover the riches of the Church Fathers so as to counter an impending ossification of Catholic theology. The Ressourcement movement was a valiant attempt by a number of theologians, de Lubac taking the lead, to breathe new life into the soul of Catholic theology so that it might simultaneously rediscover the very essence of Christianity through a return to its sources and respond to the needs and trends of modern, secular European society. Ressourcement restores relevance to theology by means of connecting with, and developing from its roots in the living reception and exposition of the revelation of Jesus Christ by the Fathers. Indeed, Ressourcement was a recapturing of Catholic tradition and patrimony.

Notes:

[1] Joseph Ratzinger, “Foreword” to Henri de Lubac, Catholicism, trans. Lancelot C. Sheppard and Elizabeth Englund (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1988), 11.

[2] In typically dramatic fashion, Hans Urs von Balthasar writes: “With Surnaturel, a young David comes onto the field against the Goliath of the modern rationalization and reduction to logic of the Christian mystery. The sling deals a death blow, but the acolytes of the giant seize upon the champion and reduce him to silence for a long time.” The Theology of Henri de Lubac: An Overview, trans. Joseph Fessio and Michael M. Waldstein (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1991), 63.

[3] “Internal Causes of the Weakening and Disappearance of the Sense of the Sacred,” in Theology in History, trans. Ann Elgund (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1996), 232.

Suggested Reading:

Henri de Lubac, At the Service of the Church: Henri de Lubac Reflects on the Circumstances that Occasioned his Writings, trans. Anne Elizabeth Englund (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1993).

Hans Urs von Balthasar, The Theology of Henri de Lubac: An Overview, trans. Joseph Fessio and Michael M. Waldstein (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1991).

Susan K. Wood, Spiritual Exegesis and the Church in the Theology of Henri de Lubac (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1998).

John Milbank, Henri de Lubac and the Debate concerning the Supernatural (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2005).

Rudolf Voderholzer and Michael J. Miller, Meet Henri de Lubac: His Life and Work (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2007).

David Grummett, De Lubac: A Guide for the Perplexed (T&T Clark, 2007).