About a week ago, Henry linked to an article by the National Catholic Reporter‘s John Allen about Rocco Buttiglione, a Catholic politician in Italy who was “a close friend” of Pope John Paul the Great and in 2004 “was rejected as a minister in the European Commission because he refused to recant his traditional Catholic beliefs on homosexuality, abortion and the family.” In his interview, he told Allen that “[t]hose who wanted [legalization of abortion] today recognize, thanks in part to scientific discoveries about the embryo and DNA, that the fetus is not a lump of blood in the body of a woman; the fetus is a life.” The interesting “twist” to the story is that Buttiglione, who clearly is not ashamed of his Catholic faith and not afraid to speak the truth about the evil of abortion even at the expense of his own career, recently stated that “he won’t support efforts to make abortion illegal, because ‘God entrusts a child to its mother in such a special way, that to defend the child against the mother is just, but impossible.'”

To a certain extent that I will explain later on in this post, I disagree with Buttiglione (and since my newfound membership in the American Catholic blogosphere has automatically conferred upon me the charism of infallibility in all matters, he’d better listen to me lest I decide to smack him with that dreaded anathema, “Catholic in Name Only”). But I bring up this story to illustrate a broader point, which is that those of us who participate frequently in the debate over legalized abortion often do not fully consider the implications of the arguments that we make. This is most blatant, of course, among those who oppose restrictions on abortion in order, they claim, to protect the mother’s right to “choose.” To this, the response is simple: “Choose to do what? To kill her child? Is that really a ‘choice’ that anyone should have?” It is also true, however, among those of us who oppose legalized abortion, in ways that are more subtle but that, in the long run, will ultimately hamper our ability to replace our current Culture of Death with a more just, more compassionate, more welcoming–in short, more Christian–society.

When we argue that an unborn child deserves legal protection, the natural followup question is simple: “From whom?” We can hem and haw about this question for as long as we desire, but in the end, if we are honest with ourselves, there is only one true answer: “From his or her mother.” And, as Buttiglione points out, it is profoundly unnatural, uncompassionate, and ultimately un-Christian to frame the issue in such a way that pits the interests of the child against the interests of his or her mother. The true failure of the pro-life movement is manifested not in election results, but in the fact that we have allowed ourselves to be dragged into the debate on the other side’s terms, under the premise that the rights and interests of a mother and her child are separate ideals that must be “balanced.”

Now, unlike Buttiglione, I do not believe that this reality completely negates the importance of a legal system that recognizes the right to life of the unborn. His argument that it is “just but impossible” to protect the life of the unborn child is, in my view, a red herring. Objectively speaking, it is fundamentally unjust–indeed, fundamentally evil–to deprive an entire class of humans of this recognition. One might just as easily and accurately say that it would be “just but impossible” to try to eliminate racism in America by legal means, but few would argue that Martin Luther King and Cesar Chavez were wrong in seeking legal protection for minorities even as they recognized that only a profound shift in cultural awareness would completely exorcise the demon of bigotry that underlay the segregated legal regime.

So must it be with the pro-life movement in modern America. For the sake of justice, we must continue to fight for laws that recognize the inalienable right to life possessed by every human being from conception until natural death. In a larger sense, however, if we wish to create a true Culture of Life, a true Civilization of Love, we cannot merely be satisfied with overturning Roe and changing a few laws. We must, as Buttiglione implies, ask ourselves a difficult question: “How in God’s Name did we as a society ever get to the point where we take for granted the idea that a child must be protected from its mother, that the rights of a child and the rights of its mother must always be mutually exclusive? And how do we as a society begin our retreat from this damnable proposition?”

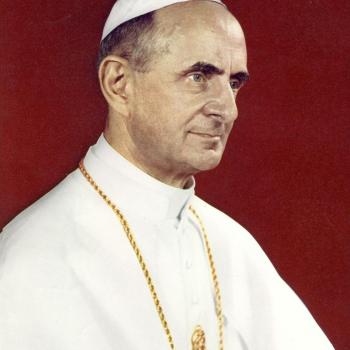

There are, I believe, two equally valid (and indeed interrelated) answers to this question, answers that point to the heart of the challenge we face in building a society that is more hospitable to all innocent life. One answer will please conservatives–as Pope Paul VI predicted in Humanae Vitae, the cultural mentality that human sexuality should be viewed only as a private, selfish means of pleasure, and not primarily as the sacred act of passing on life (and therefore an act requiring maturity, responsibility, and, God forbid, rules), has led quite logically to the idea that an unborn child is nothing more than an inconvenient byproduct that can quickly and easily be excised if it interferes with the attainment of such pleasure. The other answer will please liberals–we have allowed American capitalism to devolve into a materialist, consumerist orgy that is stacked to favor the wealthy and leave behind the vulnerable. The fact that for many poor and even middle-class women an unplanned pregnancy represents an economic catastrophe is not an invention of a pro-choice propoganda machine, nor is it simply a cop-out for Catholic Democrats who fear running afoul of their party on the legality issue; it is a frightening and, from a Christian perspective, morally repugnant reality.* Those who ignore this reality, or who resist addressing it on a national level for fear of undermining the “free market,” contribute to the notion of a clash between the (very real) needs of the mother and the inalienable rights of her unborn child.

Those of us who call ourselves pro-life need to get serious about addressing these broader cultural issues that have pitted mothers against children, not just through personal charity (for many pro-life Americans do dedicate quite a bit of time, energy, and money to supporting pregnant women through crisis pregnancy centers, and to ensuring that their children receive a proper formation on the true purpose and sacredness of human sexuality) but also through the policies for which we advocate on a national level. For their part, if our fellow citizens who call themselves pro-choice believe, as they say, that abortion is not ideal and should be more rare, they too must work to address these issues. A true common-ground effort to reduce abortion, such as the initiative that Rocco Buttiglione is now putting together, must comprehensively address both the economic factor (a topic about which liberals are more comfortable speaking but seemingly unwilling to address in any truly revolutionary way) and the moral factor (a topic about which liberals are decidedly uncomfortable, since it requires an admission that a totally sexually permissive culture is not, in fact, a good thing). Only when we begin to tackle these difficult issues will we begin to eliminate the false dichotomy that our culture has constructed between the well-being of mothers and the rights of their unborn children.

*Anyone who doubts that the American economic system has become inexorably stacked against the poor, and particularly poor women, would do well to read Nickel and Dimed. The author is Barbara Ehrenreich, a freelance writer who on three separate occasions attempted to cover basic living expenses for a month–food, rent in the cheapest accomodations possible, etc.–by working at several common minimum-wage jobs. Even without children to support, and even while working two or three jobs at a time, she was unable to make ends meet. Though Ehrenreich is an atheist and at several points in the book is quite vocal about her beliefs (or lack thereof), her findings should make it clear that America’s current system of materialistic capitalism is simply incompatible with Christian morality. Indeed, her firsthand observations of the Church’s failure to live up to the words of Her Savior on issues of economic justice should be cause for some profound self-examination on the part of all of her Christian readers.