The Spirit of Revolution

The 1880s felt like a change in the ages. Innovations younger than fifty years old included: germ theory, anesthesia, dynamite, skyscrapers, telephones, railroads, electrification, and the books of Jules Verne.

Also new: the sensational ideas of Freud, the anti-religious utopianism of Marx, and the ideological tremors of Darwinism. And, under a banner of freedom from religion, the great abbey church at Cluny – for centuries, the biggest church in the world – had been turned into a quarry, the lead of its stained glass salvaged for Napoleon’s bullets.

Was the fate of Cluny the future of the faith? Could a creed that flourished in slower ages wield any influence in an age of speed? Would technological progress bring so much of nature under human control that God would be forgotten?

Against this backdrop, Pope Leo XIII promoted St. John Damascene, dead some eleven hundred years, as the 22nd Doctor of the Church. Why him, why now?

John Damascene (also called John of Damascus) lived during an era of dramatic change, too: Islam, barely a century old, was challenging the Byzantine Empire. In the middle of his career, he encountered a sudden, extreme movement to smash religious icons.

He defied both an emperor and a caliph to defend the practice of venerating images, saying, “The truth was stronger than the majesty of kings.” Defiance led to trumped-up charges, which led to the punitive taking of his hand.

Perhaps Pope Leo thought a saint who risked his life for icons could teach a new age of Christians how to care for their treasures.

Graveyard Shift

Looking back into history, we should not take it for granted that an iconoclastic conflict was inevitable, or that John Damascene was fated to see it.

Why did icons come into question after six centuries of faithful Christians freely using them for catechesis and prayer?

In AD 722, when the crisis began, the Byzantine Empire still held sway in most of the Old Roman Empire’s East. As a religion, Islam was brand new, but it had already launched the Rashidun Caliphate.

John’s father had survived that caliphate’s takeover of Damascus, even maintaining his Christian faith and his position as a court officer. John followed his father’s footsteps in the court, so he had a front row seat for all the ways Islam was testing Byzantine Christianity.

The seed of the Islamic critique of icons was implicit in Islamic practice: no depictions of Mohammed or Allah were permitted in any setting. The critique was bolstered by Islam’s claim to the heritage of the Hebrew Scriptures, which seemed to forbid in stark terms the making of any “graven images.”

To the Islamic mindset, even the most gorgeous mosaic of the face of Christ represented syncretism, superstition, and idolatry. How could Christians, the supposedly monotheistic heirs of Judaism, make allowances for such a blatantly pagan practice as the burning of a candle before a painting? Worse, such candles often burned before images of dead men and women, not even the deity!

These critiques proved persuasive to the Byzantine emperor, several bishops, and no small number of the faithful. Icons were burned, church walls repainted, statues turned to rubble; surely the saints would be glad to face martyrdom in effigy for the sake of purifying the Church!

Defending Praxis

In answer, John Damascene spoke for a faith that is not only a book, nor merely an institution, nor just a constellation of ideas, but is a richly lived tradition, reliably guided by the Holy Spirit: lex orandi, lex credendi.

The benefit of the doubt goes to the practice of such a faith over time; if not, we must throw out our claims that God is guiding the Church. The theological defense of icons, then, is a matter of meditation and reflection, and does not represent an emergent need for de novo ideas.

Doctrine that has lain implicit and unquestioned must now be articulated, elaborated, and openly proclaimed. The Church must unfold the faith, mapping teachings to the newly asked questions.

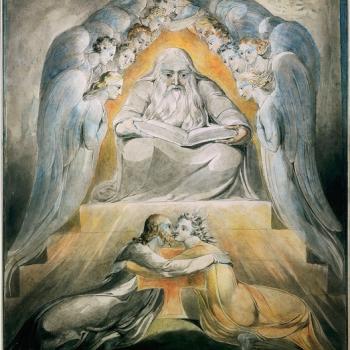

To John, prayer before icons is not nearly as scandalous as the idea that words, ideas, and things in general could help us know God. Images of God as an aggrieved lover or mother hen in the book of Hosea are already more fundamentally controversial. He wrote:

How could one picture the inconceivable? How could one express the limitless, the immeasurable, the invisible? How give infinity a shape? How paint immortality?

But when you think of God, who is a pure spirit, becoming man for your sake, then you can clothe him in a human form. When the invisible becomes visible to the eye, you may then draw his form. When he who is a pure spirit, immeasurable in the boundlessness of his own nature, existing as God, takes on the form of a servant and a body of flesh, then you may draw his likeness, and show it to anyone who is willing to contemplate it.

Ah - the missing piece is not fancy metaphysics, but the person of Jesus Christ, the Son of God who became incarnate so that He might be knowable.

In defense of icons, we must not invent the field of aesthetics but speak of our Lord. He has shown us his face, and so we may paint it. We imitate Christ the teacher when we appropriate his method of teaching.

The people who awaited a messiah could not use matter in the same way, for it had not been redeemed. That people, beset by seductive pagan totems, had not access to the same grace and had to rely heavily on prescribed practice.

Eighth century Christians made use of matter at every turn – bread, wine, water, oil, paint – for the Incarnation authorized and even mandated such use.

None of this is to say that it isn’t possible for a believer to abuse icons – one can stray from even the best-marked path. But superstition is not born in an image of the Virgin and Child, but in a sinful heart, and it can affect any act of worship.

When a person attempts to control the divine, he has forgotten the faith. For prayer to be holy in all its modes, the community must refine its rites, and individuals must examine their consciences.

Defending Development

A meditation on the Incarnation yields a sufficient defense of venerating icons.

If, however, you need more sophisticated thinking to get over the stumbling block that is icon veneration, John Damascene can give you that. Here are some pieces of that thinking:

John warns against drawing too bright a line between words and pictures. Language of any kind can only approximate ultimate truth, even if it comes very close.

Indeed, human thought itself is an application or reception of a proposed truth, and the system is neither perfectly efficient nor free from interpretation. In other words, we cannot escape representation, even in the hearing of the Good News.

In the Old Testament, God clothes himself with language. If we can justify the representation worked through words in Holy Scripture, then we may allow representation worked through paint, wood, and gold leaf.

John, often considered the last of the fathers and the first of the scholastics, wrote the first major work of systematic theology. He was interested in how all the pieces fit together, and he wanted to explore how the insights of Plato, Aristotle, and the Stoics can be reconciled with or can help to illustrate the apostolic revelation preserved in Scripture and Sacred Tradition.

The faithful human mind, though always humble before the sublime, cannot help but seek understanding. New questions arise and new formulations of ancient truths will be needed, even if only for translations.

Over a millennium before Cardinal Newman published An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine (which should one day earn Newman a spot on the canon of doctors), John Damascene showed that all theology is, by its very nature, a development of doctrine.

John Damascene’s justification of iconodulia, the veneration (not worship!) of icons, is a premier example of development of doctrine.

For older examples, we could look to the Pharisees’ expounding of the idea of a resurrection and acceptance of more books as scriptural, juxtaposed with the Sadducees’ rejection of both.

Some Christian groups do not see that they, too, have carried seeds of ideas to later conclusions.

Yet, if you want to speak of the Logos, you will need language, and if you are using language, you are using ideas, and if an idea is elaborated even a little, you are developing doctrine.

Defending Beauty

Contemplation of the faith gives rise to cathedrals and icons, not just tomes and poems. A fresco might give better testimony than an encyclical.

The waves of Protestant iconoclasm that crashed onto the shore of Renaissance-era Christianity swept many things out to sea (though it left there on the beach a jetsam of nativity scenes, gilt-framed portraits of former pastors, youth picture Bibles, and statues of American’s founding fathers).

Beauty and iconography, it seems, still need John Damascene and his latter age disciples to speak for them.

Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger once said, “A theologian who does not love art, poetry, music, and nature can be dangerous. Blindness and deafness toward the beautiful are not incidental: they necessarily are reflected in his theology.”

Later, as pope, he remarked, “The way of beauty is a privileged and fascinating path on which to approach the mystery of God.”

John Damascene walked that path of beauty. He adored as beautiful the Trinity, “imaged by the sun, or light, or burning rays, or by a running fountain, or a full river, or by the mind, speech, or the spirit within us, or by a rose tree, or a sprouting flower, or a sweet fragrance.”

A theologian both of delight and of precision, a man who attended both to current affairs and to the eternal invisible, a man who loved both natural and man-made beauty, John Damascene is a saint for all ages.

Pope Leo was right to call upon him to teach us technocrats a lesson in what it means to be fully alive in Christ.

Notes

For more textual samples from John Damascene’s On Holy Images, Fordham University provides this. You can also see another excerpt here.

You can find a concise but more encyclopedic account of John’s career in these remarks from Pope Benedict XVI, and an even shorter account here.

For a better glimpse into the mind of Pope Leo XIII, read his most influential encyclical, Rerum Novarum, and be prepared to hear an excoriation of both revolutionaries who upend in the name of labor and those who oppress the poor in the name of capital.

If you have not read Newman’s Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine, you have missed one of the theological highlights of the last 200 years.

John Damascene had a famous reader: Thomas Aquinas, who built on the ideas on methods of Damascene. For a primer on Aquinas, go here.

Modern children appear to be at little risk from confusing a holy card or backyard statue as a locus of magical power. Celebrity influencers digitally editing themselves into gods pose a bigger threat.

Disputatious ideologies aspire to be the new idols of our civilization. For a discussion of best practices in defense against them, read Dwight Longenecker’s Beheading Hydra.

11/24/2021 4:33:14 PM