Adobe Stock

Last month, in my interview with environmental studies scholar Victoria Machado, I was reminded of Catherine Albanese’s words: “the task of humanities scholarship was to make the strange familiar and the familiar strange.”

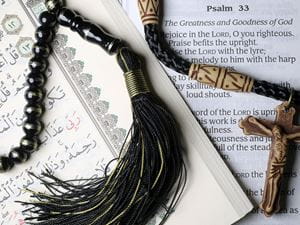

Ever since my first “Introduction to World Religions” course in college, I’ve always found this to be religious studies’ gift. Though that course used the classic “world religions” paradigm and did little to challenge reified notions of what counts — or doesn’t — as “religion,” I walked away with a deeper appreciation for how peculiar my own beliefs and practices could be and how wonderfully banal and ordinary the rituals and traditions of the supposed religious “Other” became when situated within their social, political or economic context.

Another gift of that first encounter with the study of religion was the understanding that religious communities have not only had to come to terms with one another over the millennia but have been mutually shaped by their respective conventions and worldviews.

Coming of age as a Lutheran kid in the shadow of 9/11 and living in a decidedly multi-religious urban context, I have been particularly struck by the many and various ways Islam played a crucial role in the shape of Christian thought and practice, from the Middle Ages to the present day.

That is why, when I came across Mehmet Karabela’s Islamic Thought through Protestant Eyes (Routledge, 2021) I was intrigued by his exploration of how (mostly) German Lutherans engaged with Islamic thought and helped give shape to Protestant identity in the wake of the Reformation. Karabela’s contribution further testifies to the ways in which the “strange” is not only more “familiar” than we at first might think but has played a role in the evolution of our own thought and practice. It is also a cautionary tale for how the study of religion can lead to conclusions that tell us less about the world and more about ourselves.

Islam as post-Reformation “foil”

Surveying and analyzing a range of understudied dissertations, disputations, and academic works written in Latin in the 17th and 18th centuries, Karabela details how Protestant theologians were not only deeply interested in Islamic thought and theology, but how it helped give shape to their own identifications and interpretations of the Reformation and its legacy.Writing from my office overlooking a statue of 16th-century rebel monk and church reformer Martin Luther in Eisenach, Germany — in the heart of the “Land of the Reformation” — I am reminded of how the story of the Protestant Reformation is often told according to a “great man theory” approach to history. The stories we tell, and myths we make, center around heroes like Luther and Ulrich Zwingli, Jan Hus, or John Calvin. But taking a global historical approach to the development of thought and intra-Protestant rivalries in the wake of the Reformation, Karabela adroitly illustrates “how post-Reformation Protestant thinkers engaged with Islam and used it as a foil to differentiate themselves from Catholics” and others (1). In other words, he sketches how the Reformation and its aftermath were not solely European or Christian phenomena, but impacted by and imbricated with Islamic society, culture, and religion.

Turning to unpublished dissertations and other works by Protestant scholars at universities in cities like Wittenberg, Leipzig, Halle, Jena, and Danzig, Karabela shows how European Christians were keenly interested in Islamic theology, philosophy, and intra-Muslim divisions (e.g., Sunni and Shi‘a). Their works delve deeply into Quranic studies, Islamic theology, Islamic morality and Turkish politics, Arabic literature and the concept of predestination.

Take, for example, August Pfeiffer, an adjunct professor at Wittenberg who taught oriental languages and came to have an outsized influence on the faith and thought of famed Lutheran composer Johann Sebastian Bach (ch. 5). His work, appearing in Leipzig in 1687, “presents Islam as a corruption of Christianity,” (153) as well as Judaism, Islam, and Catholicism as religions of “empty ceremonies and ritual…rather than true faith.” (156) These verbal barbs were not only estimations of the religious “Other,” but Pfeiffer’s critical comments on 17th-century Lutheran Pietism and a Protestant reformist movement known as the Calixtinians. Though Pfeiffer certainly had sharp words for what he saw as Islamic errors (e.g., that it was a “misguided amalgamation” of paganism, Judaism, and Christianity), his interpretation of Islamic intellectual history was very much about his zealous advocacy for “Lutheran Orthodoxy.”

Then there is Karabela’s analysis of Samuel Schelwig, another proponent of Lutheran Orthodoxy who tussled with Pietist leaders like Philipp Jacob Spener. Though Schelwig admired “Islamic ethical practices related to judicial testimony, business dealings, and charity” (209) as well as acknowledged, “that the Turks made important contributions to grammar, rhetoric, and dialectic,” (210) he largely sought to discredit Islamic practice and teachings. He did so for two reasons: first, to distinguish Protestant Europe from Islamicate lands and second, to take side swipes at his continental theological rivals. For example, Karabela explains how Schelwig negatively compared Sufi dervishes — ascetic mendicants who dedicated themselves to prayer, meditation, fasting, and seeking hidden spiritual guidance in the Quran — to Catholic Jesuits and other Christian mystics. In doing so, Karabela writes, “Schelwig kills two birds with one stone: extending his negative appraisal to Pietism as well as Catholicism.” (210)

Together, Karabela’s analysis of works by theologians like Pfeiffer and Schelwig shows, “how Lutheran scholars used Islamic thought to further define their new religious identity in the context of intra-Christian…and intra-denominational disputes.” (8)

Constructing ourselves through the religious “Other”

As a contemporary Lutheran, I appreciate how Karabela lays bare how my theological forebears’ engagement with Islamic thought and practice was sometimes less about Islam and Muslims as such, but very much about their own identifications and theological orientations. Or, as Karabela puts it, that their keen interest in Islam was less about understanding the religion on its own terms and much more concerned with using Islam as “a field of battle” to wage war against all types of religious “Others”: Pietists and Catholics, minority movements and Muslims themselves.However, and on a more scholarly note, I also appreciate how Karabela’s analysis hints at the antecedents of what has now come to be known as “Orientalism.” Orientalism, as a body of theory and practice that imagines, constructs, and distorts depictions of the “Orient” or the “East” in order to bolster the identity and supposed superiority of the “West,” has long been limited to the age of colonialism and empire-building. Though this is certainly when Orientalism came of age, Karabela illustrates how these Protestant thinkers were not only motivated in their critiques by certain geo-political realities (e.g., they felt threatened by the Ottoman Empire’s expansion and the present of Muslims in and around Europe) but positioned Islam and Muslims as the antithesis to their own sense of superiority and self.

Furthermore, I think it bears saying that their critiques of Islam, which were not-so-veiled attacks on Catholics and intra-Protestant rivals, continue to reverberate in Protestant thought to this day. The claims that Islam is a patchwork religion and that it is not rational, or that Muslims are morally lax, anti-intellectual, and overly enthusiastic, are not sequestered to the unpublished works of otherwise obscure Lutheran theologians in Germany, Sweden, Poland, or England. They are preached in contemporary Protestant pulpits, published on blogs and in denominational magazines, and shared at congregational Bible studies or social gatherings.

As Lutherans, Karabela’s work might give us pause to think on how we are still using Islam to solidify our own identifications and personal positions. How might we, in reading Karabela’s book, consider how the discourse around Islam and Muslims in our classrooms, congregations, or conferences is less about making Islam more familiar to our communities on its own terms, but more about our own insecurities, intra-denominational politics, and sense of loss amidst the shift from formerly Christian privilege to contemporary spiritual plurality and miscellany?

Furthermore, it might give students of religion pause when thinking about the study of things “strange” and “familiar.” Though the goal of making the familiar, strange and the strange, familiar might be laudable, we should also be aware of how interpreting the religious, cultural, social, or political “Other” through the lens of our own perspectives and position in the world can be fraught with distorting dangers.

By deftly teasing out how Islamic thought influenced the construction of Protestant identity after the Reformation, Karabela not only helps us further comprehend Islam’s role in Christianity’s evolution, but how the study of religion must always be aware of its inherent biases, social and political positioning, and tendency to misunderstand in the pursuit of knowledge and understanding.

12/5/2024 1:05:52 AM